Wikileaks: Is Julian Assange interfering in US election?

By Tom Spender

Julian Assange is not a hero. And he certainly isn’t a journalist. He manipulated document leaks for his personal political motivations in 2016. And those actions directly led to 1.6.21. -dayle

WATCH.

BBC

Wikileaks: Is Julian Assange interfering in US election?

By Tom Spender

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-37704393

~

NYTimes

Assange, Avowed Foe of Clinton, Timed Email Release for Democratic Convention

Hillary Clinton says Julian Assange colluded with Russia to help Donald Trump win US election

Ex-Ecuadorian president confirms Assange meddled in US election from London embassy

Assange helped sabotage U.S. election, remember?

December 6, 2021

THE ATLANTIC

‘Cover story by Barton Gellman on a Republican Party still in thrall to Donald Trump—and better positioned to subvert the next election than it was the last.’

“The next attempt to overthrow a national election may not qualify as a coup. It will rely on subversion more than violence, although each will have its place. If the plot succeeds, the ballots cast by American voters will not decide the presidency in 2024. Thousands of votes will be thrown away, or millions, to produce the required effect. The winner will be declared the loser. The loser will be certified president-elect.”

Mr. Winter is a staff photographer on assignment in Opinion. Mr. Wegman is a member of the editorial board.

‘Earlier this year we asked Floridians whose voting rights had been denied because of a criminal conviction to sit for photographs, wearing a name tag that lists not their name but their outstanding debt — to the extent they can determine it. This number, which many people attempt to tackle in installments as low as $30 a month, represents how much it costs them to win back a fundamental constitutional right, and how little it costs the state to withhold that right and silence the voices of hundreds of thousands of its citizens. The number also echoes the inmate identification number that they were required to wear while behind bars — another mark of the loss of rights and freedoms that are not restored upon release.

This is the way it’s been in Florida for a century and a half, ever since the state’s Constitution was amended shortly after the Civil War to bar those convicted of a felony from voting. That ban, like similar ones in many other states, was the work of white politicians intent on keeping ballots, and thus political power, out of the hands of millions of Black people who had just been freed from slavery and made full citizens.

Even as other states began reversing their own bans in recent years, Florida remained a holdout — until 2018, when Floridians overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment restoring voting rights to nearly everyone with a criminal record, upon the completion of their sentence. (Those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense were excluded.)

Democratic and Republican voters alike approved the measure, which passed with nearly two-thirds support. Immediately, as many as 1.4 million people in the state became eligible to vote. It was the biggest expansion of voting rights in decades, anywhere in the country.

That should have been the end of it. But within a year, Florida’s Republican-led Legislature gutted the reform by passing a law defining a criminal sentence as complete only after the person sentenced has paid all legal financial obligations connected to it.

Even relatively small debts can be permanently disenfranchising for people who simply don’t bring in enough money to pay them off. General Peterson, 63, served a total of three and a half years on three convictions and believes he still owes around $1,100 in fees. He is retired and using his Social Security check to make monthly payments of $30 on the debt. “You want to help me pay it? That’d be fine with me,” he said.’

The vacuum created by the collapse of independent local news in America has given rise to ghost papers, partisan hackery, unverified rumors, and worse. Yet, new cohorts of news organizations are taking root to fill that void, often supported by philanthropy, public contributions, and new creative means of sustainability. At stake is the information that all citizens need to participate in democracy. S. Mitra Kalita, co-founder and CEO of URL Media, a network of Black-and Brown-owned media organizations sharing content, distribution, and revenues, and Stewart Vanderwilt, president and CEO of Colorado Public Radio, discuss the changing landscape of news gathering with Vivian Schiller, executive director of Aspen Digital at the Aspen Institute.

NYTimes

David Brooks

“In 1982, the economist Mancur Olson set out to explain a paradox. West Germany and Japan endured widespread devastation during World War II, yet in the years after the war both countries experienced miraculous economic growth. Britain, on the other hand, emerged victorious from the war, with its institutions more intact, and yet it immediately entered a period of slow economic growth that left it lagging other European democracies. What happened?

In his book “The Rise and Decline of Nations,” Olson concluded that Germany and Japan enjoyed explosive growth precisely because their old arrangements had been disrupted. The devastation itself, and the forces of American occupation and reconstruction, dislodged the interest groups that had held back innovation. The old patterns that stifled experimentation were swept away. The disruption opened space for something new.

Something similar may be happening today. Covid-19 has disrupted daily American life in a way few emergencies have before. But it has also shaken things up and cleared the way for an economic boom and social revival.

Millions of Americans endured grievous loss and anxiety during this pandemic, but many also used this time as a preparation period, so they could burst out of the gate when things opened up. After decades of slowing entrepreneurial dynamism, 4.4 million new businesses were started in 2020, by far a modern record. A report from Udemy, an online course provider, says that 38 percent of workers took some additional training during 2020, up from only 14 percent in 2019.

After decades in which consumption took preference over savings, Americans socked away trillions of dollars in 2020, reducing their debt burdens to lows not seen since 1980 and putting themselves in a position to spend lavishly as things open up.

The biggest shifts, though, may be mental. People have been reminded that life is short. For over a year, many experienced daily routines that were slower paced, more rooted, more domestic. Millions of Americans seem ready to change their lives to be more in touch with their values.

The economy has already taken off. Global economic growth is expected to be north of 6 percent this year, and strong growth is expected to last at least through 2022. In late April, Tom Gimbel, who runs the recruiting and staffing firm LaSalle Network, told The Times: “It’s the best job market I’ve seen in 25 years. We have 50 percent more openings now than we did pre-Covid.” Investors are pouring money into new ventures. During the first quarter of this year U.S. start-ups raised $69 billion, 41 percent more than the previous record, set in 2018.

Already, this era of new creation seems to be rebalancing society in at least three ways:

First, power has begun shifting from employers to workers. In March, U.S. manufacturing, for example, expanded at the fastest pace in nearly four decades. Companies are desperate for new workers. Between April 2020 and March 2021, the number of unemployed people per opening plummeted to 1.2 from 5.

Workers are in the driver’s seat, for now, and they know it. The “quit rate” — the number of workers who quit their jobs because they are confident they can get a better one — is at the highest in two decades. Employers are raising wages and benefits to try to lure workers back.

Second, there seems to be a rebalancing between cities and suburbs. Covid-19 accelerated trends that had been underway for a few years, with people moving out of big cities like New York and San Francisco to suburbs, and to rural places like Idaho and the Hudson Valley in New York. Many are moving to get work or because of economic distress, but others say they moved so they could have more space, lead slower-paced lives, be closer to family or interact more with their neighbors.

Finally, there seems to be a rebalancing between work and domestic life. Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom expects that even when the pandemic is over, the number of working days spent at home will increase to 20 percent from 5 percent in the prepandemic era.

While this has increased pressures on many women, millions of Americans who could work remotely found that they liked being home, dining every night with their kids, not hassling with the commute. We are apparently becoming a less work-obsessed and a more domestic society.

In 1910 the educator Henry Van Dyke wrote, “The Spirit of America is best known in Europe by one of its qualities — energy.” That energy seemed to be fading away in recent years, as Americans came to move less and start new businesses less frequently. But the challenge of Covid-19 has summoned forth great dynamism, movement and innovation. Labor productivity rates have surged upward recently.

Americans are searching for ways to make more money while living more connected lives. Joel Kotkin, a professor of urban studies at Chapman University, points out that as the U.S. population disperses, economic and cultural gaps between coastal cities and inland communities will most likely shrink. And, he says, as more and more immigrants settle in rural areas and small towns, their presence might reduce nativism and increase economic competitiveness.

People are shifting their personal lives to address common problems — loneliness and loss of community. Nobody knows where this national journey of discovery will take us, but the voyage has begun.”

To understand the world knowledge is not enough, you must see it, touch it, live in its presence.

—Teilhard de Chardin, Hymn of the Universe

The American Lie.

No. Not the election.

The big lie in the United States is racism only effects people of color.

Heather McGhee’s book is brilliant. She is brilliant. Her book is incredibly researched and synthesized. A must read book for every journalist, politician, policy creator, and student. Actually, you know what? Everyone should read Heather’s book. And she speaks like she writes, clearly, foundationally, and directly. We need to listen. -dayle

NPR/Fresh Air

The heart of McGhee’s case is that racism is harmful to everyone, and thus we all have an interest in fighting it. Drawing on a wealth of economic data, she argues that when laws and practices have discriminated against African Americans, whites have also been harmed. When people unite across racial and ethnic lines, she argues, there’s a solidarity dividend that helps everyone.

Heather McGhee is the former president of the progressive think tank Demos, where she spent much of her career. She holds a BA in American Studies from Yale and a law degree from the University of California, Berkeley. She currently chairs the board of Color of Change, a nationwide online racial justice organization. Her new book is “The Sum Of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone And How We Can Prosper Together.”

Heather McGhee:

This to me is really the kind of parable at the heart of the book. It’s what’s illustrated on the cover. In the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, the United States went on a building boom of these grand resort-style swimming pools. These were the kind that would hold hundreds, even thousands, of swimmers. And it was a real sort of Americanization project. It was to create a, like, bath-temperature melting pot of, you know, white ethnic immigrants and people in the community to come together. It was sort of a commitment by the government to a leisure-filled American dream standard of living. And in many of these public pools, the rule was that it was whites only, either officially or unofficially. And in the 1950s and ’60s when Black communities began to, understandably, say, hey, it’s our tax dollars that are helping to support this public good, we need to be allowed to swim, too, all over the country, particularly in the American South but in other places as well, white towns facing integration orders from the courts decided to drain their public swimming pools rather than let Black families swim, too.

Now, I went to Montgomery, Ala., where there used to be one of those grand resort-style pools and where effective January 1, 1959, not only did they back a truck up and pour dirt into the pool and pave it over, but they also sold off the animals in the municipal zoo. They closed down the entire parks and recreation department of Montgomery for a decade. It wasn’t until almost 1970 that they reopened the park system for the entire city. And I walked the grounds of Oak Park. Even after they reopened it, they never rebuilt the pool. And that, to me, felt like this just tangible symbol of the way that a population taught to distrust and disdain their neighbors of color will withdraw from public goods when they no longer see the public as good.

Interview with Dave Davies on NPR:

https://www.npr.org/2021/02/17/968638759/sum-of-us-examines-the-hidden-cost-of-racism-for-everyone

The Daily Show with Trevor Noah

“The Sum of Us,” and underlines the importance of having honest conversations about past and present racism at a community level.

Ezra Klein/NYTimes

What ‘Drained-Pool’ Politics Costs America

I asked McGhee to join me on my podcast, “The Ezra Klein Show,” for a discussion about drained-pool politics, the zero-sum stories at the heart of American policymaking, how people define and understand their political interests, and the path forward. This is, in my view, a hopeful book, and a hopeful conversation. There are so many issues where the trade-offs are real, and binding. But in this space, there are vast “solidarity dividends” just waiting for us, if we are willing to stand with, rather than against, each other.

Also from the NYTimes.

opinion

The book That Should Change How Progressives Talk About Race

Heather McGhee writes that racism increases economic inequality for everyone.

by Michelle Goldberg

McGhee’s book is about the many ways racism has defeated efforts to create a more economically just America. Once the civil rights movement expanded America’s conception of “the public,” white America’s support for public goods collapsed. People of color have suffered the most from the resulting austerity, but it’s made life a lot worse for most white people, too. McGhee’s central metaphor is that of towns and cities that closed their public pools rather than share them with Black people, leaving everyone who couldn’t afford a private pool materially worse off.

One of the most fascinating things about “The Sum of Us” is how it challenges the assumptions of both white antiracism activists and progressives who just want to talk about class. McGhee argues that it’s futile to try to address decades of disinvestment in schools, infrastructure, health care and more without talking about racial resentment.

[…]

“Communicators have to be aware of the mental frameworks of their audience,” McGhee told me. “And for white Americans, the zero-sum is a profound, both deeply embedded and constantly reinforced one.”

This doesn’t mean that the concept of white privilege isn’t useful; obviously it describes something real. “What privilege awareness does, at its best, is reveal the systematic unfairness, and lift the blame from the victims of a corrupt system,” McGhee said. “However, I think at this point in our discourse — also when so many white people feel deeply unprivileged — it’s more important to talk about the world we want for everyone.”

Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Theologian Howard Thurman, from Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary [1984].

Thurman takes what is personal and makes it universal. Walter Brueggemann calls this “the scandal of particularity.” [1] We “get it” in one ordinary, concrete moment and wrestle and fall in love with it there. It’s a scandal precisely because it’s so ordinary. What is true in one place finally ends up being true everywhere.

From Barbara Holmes and her lecture Race and the Cosmos, unpublished Living School curriculum.

As I considered it, the truth of the matter was that we were living within an old story; and a new story needed to be told, but we didn’t have the language for it.

The old story was of victimization, marginalization, oppression, oppressors; and the new story would see all of us evolving, self-expanding, and finding a new place in this wonderful cosmology that is a reality we have not paid attention to. So, in order to get to that point—and here is where my transformation begins—I had to reconsider what I thought about people, because I had hardened my view of others and who they were and what they meant. I had spent my time raising two little African American boys who had to be taught how to survive in society. In doing that, I taught them to view the world in only one way; and I myself was hardened into a position that either you were with me or you were against me or us.

All of that had to change. I had to begin to think of us as spiritual beings having a human experience, and not bodily, embodied folks without spirit or soul. . . . That’s a very limited view of humankind, and I wanted to expand the story. . . .

The physics and cosmology revolution that is 100 years old has not been translated into the ordinary world of any of us, and specifically not in communities of color. The world that scientists describe now is so different than the world that I grew up in or even imagined. According to physicists, this is what the world is like: it is a universe permeated with movement and energy that vibrates and pulses with access to many dimensions. . . . We are all interconnected, not just spiritually or imaginally, but actually . . . and the explicate [or manifested] order that’s all around us makes us think that we’re separate. Finally, I learned that ideas of dominance are predicated on a Newtonian clockwork universe. So, like dominoes, you push one and they all fall down, and everything is in order. But quantum physics tells us that the world is completely different. Particles burst into existence in unpredictable ways, observations affect the observed, and dreams of order and rationality are not the building blocks of the universe.

A compilation piece: 2-part documentary on PBS, The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song, from executive producer, host, and writer Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

It traces the 400-year-old story of the Black church in America, all the way down to its bedrock role as the site of African American survival and grace, organizing and resilience, thriving and testifying, autonomy and freedom, solidarity and speaking truth to power.

It is now available online.

https://www.pbs.org/show/black-church/

Cicely Tyson December 19, 1924 – January 28, 2021

During the Nixon administration in the 1970’s, the FCC called the Fairness Doctrine the “single most important requirement of operation in the public interest” (Becker, 2017, para. 8)

Becker, W. (2017, Feb. 23). What’s behind Trump’s war with the press? Huffpost.

Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/whats-behind-trumps-war-with-the-press_us_58addf5ce4b0598627a55f9e

Seth Godin:

The internet clearly has a trust problem. As with most things, it helps to start with the Grateful Dead.

After their incarnation as the Warlocks, they became more than a band. It was a family on the road. There were people who gave up their careers to follow them around, living on buses… they were seeing thirty or forty shows a year. You traded tickets, did favors, built relationships. People in the family knew that they’d be seeing each other again soon.

And then, in 1987, Touch of Grey went to #1 (their only top 40 hit) and it attracted a huge (and different) crowd to the shows. Reports were that the intimacy and trust disappeared.

Glen Weyl points out that the internet was started by three tribes, as different from each other as could be. The military was behind the original ARPA (and then DARPA) that built and funded it. Professors at universities around the world were among the early users. And in San Francisco, a group of ‘hippies’ were the builders of some of the first culture online.

Because each of these groups were high-trust communities, it was easy to conclude that the people they’d be engaging online would be too. And so, as the tools of the internet and then the web were built out, they forgot to build a trust layer. Plenty of ways to share files, search, browse, chat and talk, but no way to engage in the very complicated things that humans do around identity and trust.

Humans have been in tribal relationships since before recorded history began. The word “tribe” appears in the Bible more than 300 times. But the internet isn’t a community or a tribe. It’s simply a technology that amplifies some voices and some ideas. When we don’t know who these people are, or if they’re even people, trust erodes.

When a site decides to get big fast, they usually do it by creating a very easy way to join, and they create few barriers to a drive-by anonymous experience. And when they make a profit from this behavior, they do it more. In fact, they amplify it.

Which makes good business in the short run, but lousy public policy.

Twenty years ago, I wrote that if someone goes into a bank wearing a mask (current pandemic aside) we can assume that they’re not there to make a deposit.

And now we’re suffering from the very openness and ease of connection that the internet was built on. Because a collection of angry people talking past each other isn’t a community. Without persistence of presence, some sort of identity and a shared set of ideals, goals and consequences, humans aren’t particularly tempted to bring their best selves to the table.

The system is being architected against our best impulses. Humans understand that local leadership, sacrifice and generosity build community, and that fights and scandals simply create crowds. Countless people are showing up, leading and pushing back, but algorithms are powerful and resilient, and we need some of them to be rebuilt.

Until there’s a correlation between what’s popular or profitable and what’s useful, we’re all going to be paying the price.

Opinion by Nicole Hemmer

‘The Fairness Doctrine, a regulation from the late ‘40’s until 1987, dictated balanced coverage of controversial issues on broadcast radio and television. After its repeal, Rush Limbaugh & Fox News quickly became two of the most influential political institutions in the US.

George Orwell

Want to reinstate the FCC’s Fairness Doctrine to help curb the spread of disinformation? Conservatives and liberals both may well want to reconsider that idea, argues a Columbia University scholar.’

What America needs instead is a creative, comprehensive effort by both the private sector and the government to disincentivize conspiracies and misinformation on the many platforms on which they flourish. Some social media companies have begun this work, clearing out QAnon sites and banning some far-right and White power users and communities who pose a threat.That work needs to continue, with careful attention to the biggest offenders who game algorithms and media structures to spread misinformation. But sources of misinformation also need to be demonetized, whether they are YouTube channels or national cable networks, and algorithms tweaked to slow down the spread of extreme content.’

Posted on twitter 2.4.21:

“I’m going to spend more time writing on this because this is not only a digital detox story. it’s a story about power. And it’s at the center of everything.”

“Michael Goldhaber is the internet prophet you’ve never heard of. Here’s a short list of things he saw coming: the complete dominance of the internet, increased shamelessness in politics, terrorists co-opting social media, the rise of reality television, personal websites, oversharing, personal essay, fandoms and online influencer culture — along with the near destruction of our ability to focus.

Most of this came to him in the mid-1980s, when Mr. Goldhaber, a former theoretical physicist, had a revelation. He was obsessed at the time with what he felt was an information glut — that there was simply more access to news, opinion and forms of entertainment than one could handle. His epiphany was this: One of the most finite resources in the world is human attention. To describe its scarcity, he latched onto what was then an obscure term, coined by a psychologist, Herbert A. Simon: “the attention economy.”

Advertising is part of the attention economy. So are journalism and politics and the streaming business and all the social media platforms. But for Mr. Goldhaber, the term was a bit less theoretical: Every single action we take — calling our grandparents, cleaning up the kitchen or, today, scrolling through our phones — is a transaction. We are taking what precious little attention we have and diverting it toward something. This is a zero-sum proposition, he realized. When you pay attention to one thing, you ignore something else.

The idea changed the way he saw the entire world, and it unsettled him deeply. “I kept thinking that attention is highly desirable and that those who want it tend to want as much as they can possibly get,” Mr. Goldhaber, 78, told me over a Zoom call last month after I tracked him down in Berkeley, Calif. He couldn’t shake the idea that this would cause a deepening inequality.

“When you have attention, you have power, and some people will try and succeed in getting huge amounts of attention, and they would not use it in equal or positive ways.”

More than a decade later, Mr. Goldhaber lives a quiet, mostly retired life. He has hardly any current online footprint, except for a Twitter account he mostly uses to occasionally share posts from politicians. I found him by calling his landline. But we are living in the world he sketched out long ago. Attention has always been currency, but as we’ve begun to live our lives increasingly online, it’s now the currency. Any discussion of power is now, ultimately, a conversation about attention and how we extract it, wield it, waste it, abuse it, sell it, lose it and profit from it.

While Mr. Goldhaber said he wanted to remain hopeful, he was deeply concerned about whether the attention economy and a healthy democracy can coexist. Nuanced policy discussions, he said, will almost certainly get simplified into “meaningless slogans” in order to travel farther online, and politicians will continue to stake out more extreme positions and commandeer news cycles. He said he worried that, as with Brexit, “Rational discussion of what people stand to gain or lose from policies will be drowned out by the loudest and most ridiculous.”

[Alex Kiesling]

Full article:

‘The problem is that they don’t seem to be naming the rise of racialized authoritarianism; the media’s responsibility above all (is to) sound the alarm—boost that signal — it must tell the real story of what’s going on — before it is too late.’

It cannot remain neutral when those values are under threat from racialized authoritarianism.

By

‘The media must begin to assert some agency over the stories it covers and how it covers them, based on its own values. In discussing journalistic objectivity, Rosen agrees that the media’s work should not be politicized, i.e., produced expressly to help one party/candidate or another.

On the other hand, he says, media cannot help but be political. Modern journalism was meant to play a political role, to expose the truth and hold politicians accountable to the small-l liberal values that make liberal democracy possible. It cannot remain neutral when those values are under threat. Like other institutions — science, the academy, and the US government itself — its very purpose is to both exemplify and defend those values. Its work is impossible without them.

The press should always be fair in the application of its values and standards, but doing so will mean making clear when there is an asymmetry.

The American public, by and large, does not understand this asymmetry and its implications. They do not understand that right-wing authoritarianism is perilously close to toppling US democracy because they are not able to pick that signal out of the noise of daily “balanced” news coverage, wherein everything is just another competing claim, just another good-faith argument to hash out through competing op-eds.

Even in the face of the inevitable pressure campaign from the right, even amid an information environment chocked with conspiracies and nonsense, the press must boost that signal — it must tell the real story of what’s going on — before it is too late.’

Full Article:

The stark front page of today’s New York Times, plus three inside pages, consist of two-line obituaries for 1,000 of the nearly 100,000 Americans who have died of coronavirus — 1% of the toll.

[Note: if the NYTimes had published all the names, not just the 1% of the 100,000, they would have had to punish 100 separate newspaper editions.]

A huge team at The Times drew the accounts “from hundreds of obituaries, news articles and paid death notices that have appeared in newspapers and digital media over the past few months.”

Marc Lacey, national editor, said: “I wanted something that people would look back on in 100 years to understand the toll of what we’re living through.”

Cornelia Ann Hunt, 87, Virginia Beach, her last words were “thank you.”

Professor Jay Rosen, NYU:

“The battle to prevent Americans from understanding what went down January to April is going to be one of the biggest propaganda and freedom of information fights in modern U.S. history. Data erasure and the manufacture of mass confusion have already begun.”

NYTimes

OfficialCounts Understate the U.S. Coronavirus Death Toll

[click photo to follow story link]

More than 9,400 people with the coronavirus have been reported to have died in this country as of this weekend, but hospital officials, doctors, public health experts and medical examiners say that official counts have failed to capture the true number of Americans dying in this pandemic. The undercount is a result of inconsistent protocols, limited resources and a patchwork of decision-making from one state or county to the next.

Early in the U.S. outbreak, virus-linked deaths may have been overlooked, hospital officials said. A late start to coronavirus testing hampered hospitals’ ability to detect the infection among patients with flulike symptoms in February and early March. Doctors at several hospitals reported treating pneumonia patients who eventually died before testing was available.

‘Like many in business, trusted news organizations are being hit hard by this pandemic. If you can, please consider subscribing to your local paper or contributing to a VT news organization. You deserve transparency and the truth, and they work hard to keep you informed.

-Vermont Governor Phil Scott

NYTimes

Ben Smith

“Abandon most for-profit local newspapers, whose business model no longer works, and move as fast as possible to a national network of nimble new online newsrooms. That way, we can rescue the only thing worth saving… the journalists.”

The coronavirus is likely to hasten the end of advertising-driven media, our columnist writes. And government should not rescue it.

“There’s all this ‘doom and gloom for local journalism stories’ that have happened in the last week or so, and I hope that other people see what we’re doing and understand that the important thing is the journalism — it’s the stories, it’s the investigations — that’s what matters,” Ken Ward said. He will also be on the staff of the nonprofit investigative powerhouse ProPublica and will have support from Report for America, another growing nonprofit organization that sends young reporters to newsrooms around the country.

The news business, like every business, is looking for all the help it can get in this crisis. Analysts believe that the new federal aid package will help for a time and that the industry has a strong case to make. State governments have deemed journalism an essential service to spread public health information. Reporters employed by everyone from the worthiest nonprofit group to the most cynical hedge fund-owned chain are risking their lives to get their readers solid facts on the pandemic, and are holding the government accountable for its failures. Virtually every news outlet reports that readership is at an all-time high. We all need to know, urgently, about where and how the coronavirus is affecting our cities and towns and neighborhoods.

So what comes next? That decision will be made in the next few months — by public officials, philanthropists, and other tech companies, and people like you.

The right decision is to consistently look to the future, which comes in a few forms. The most promising right now is Ms. Green’s dream of a big new network of nonprofit news organizations across the country on the model o The Texas Tribune, which Mr. Thornton co-founded. There are also a handful of local for-profit news outlets, like The Seattle Times, The Los Angeles Times and The Boston Globe, with rich and civic-minded owners, and The Philadelphia Inquirer, which is owned by the non-profit Lenfest Institute for Journalism. And there is a generation of small, independent membership or subscription sites and newsletters like Berkeleyside.

Elizabeth Green, a founder of Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization reporting on education issues, in Washington, D.C.

[Avi Schiffmann]

The New Yorker

by Brent Crane

In December, DT said, “We have a problem that, a month ago, nobody thought about.” Well, somebody did. On December 29th, as DT vacationed with his family at Mar-a-Lago, Avi Schiffmann, a seventeen-year-old from Washington State, launched a homemade Web site to track the movement of the coronavirus. Since then, the site, ncov2019.live, has had more than a hundred million visitors. “I wanted to just make the data easily accessible, but I never thought it would end up being this big,” the high-school junior said last week over FaceTime. Schiffmann, gap-toothed and bespectacled, was sitting on his bed wearing a blue T-shirt and baggy pajama bottoms. It was late morning. He was at his mother’s house, on Mercer Island, outside Seattle.

Using a coding tactic known as “web-scraping,” Schiffmann’s site collates data from different sources around the globe—the W.H.O., the C.D.C., Yonhap News Agency in South Korea—and displays the latest number of covid-19 cases. It features simple graphics and easy-to-read tables divided by nation, continent, and state. Data automatically updates every minute. In a politicized pandemic, where rumor and panic run amok, the site has become a reputable, if unlikely, watchdog.

He began teaching himself to code when he was seven, mainly by watching YouTube videos, and has made more than thirty Web sites. “Programming is a great creative medium,” he said. “Instead of using a paintbrush or something, you can just type a bunch of funky words and make a coronavirus site.” One of his first projects, in elementary school, was what he calls “a stick-figure animation hub.” Later sites collated the scores for his county’s high-school sports games, aggregated news of global protests, and displayed the weather forecast on Mars. “His brain is constantly going from one thing to another, which is good, but I also try to focus him in,” his mother, Nathalie Acher, said. “I’m not techy at all myself. I see it as just really boring. He sees it as an art form.”

Schiffmann took the virus threat seriously before many others did. “I’ve been kind of concerned for a while, because I watched it spread very fast, and around the entire world. I mean, it just kind of went everywhere.” He took his own precautions. “I got masks a while ago. I got, like, fifteen for seventeen dollars. Now you can’t even buy a single mask for, like, less than forty.” His mother chimed in. “I wish I had listened to him,” she said. “But, in his teen-ager way, he’d come down the stairs with his eyes huge and be, like, ‘There are fifty thousand more cases!’ and I’d be, like, ‘Yeah, but they’re over there, not here.’ ”

Her son is a C student.

Now that the grownups of the world are finally, and appropriately, freaking out, it is hard for Schiffmann not to feel righteous vindication. “If you told someone three months ago that we should spend, like, ten billion dollars in upgrading the United States’ health care, they would have been, like, ‘Nah,’ ” he said. “Now, everyone’s, like, ‘Oh, my God, yes.’ But this is the kind of stuff we should have done a long time ago.”

Young people give me so much hope. ❥ -dayle

Sharing a message from one of the spiritual leaders in our valley, Sun Valley, Idaho.

’Those who love their own noise are impatient of everythingelse. They constantly defile the silence of the forests and the mountains and the sea.They for through silent nature in very direction with their machines, for fear that thecalm world might accuse them of their own emptiness. The urgency oftheir swift movement seems to ignore the tranquility of nature bypretending to have a purpose. The loud plane seems for a moment to deny the realityof the clouds and of the sky by its direction, its noise, and its pretendedstrength. The silence of the sky remains when the plane has gone. Thetranquility of the clouds will remain when the plane has fallen apart. It is thesilence of the world that is real. Our noise, our business, and all our fatuous statementsabout our purposes—these are the illusions.’-No Man Is an Island [1955]

Terrifying though the coronavirus may be, it can be turned back. China, South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan have demonstrated that, with furious efforts, the contagion can be brought to heel.

Whether they can keep it suppressed remains to be seen. But for the United States to repeat their successes will take extraordinary levels of coordination and money from the country’s leaders, and extraordinary levels of trust and cooperation from citizens. It will also require international partnerships in an interconnected world.

There is a chance to stop the coronavirus. This contagion has a weakness.

Although there are incidents of rampant spread, as happened on the cruise ship Diamond Princess, the coronavirus more often infects clusters of family members, friends and work colleagues, said Dr. David L. Heymann, who chairs an expert panel advising the World Health Organization on emergencies.

No one is certain why the virus travels in this way, but experts see an opening nonetheless. “You can contain clusters,” Dr. Heymann said. “You need to identify and stop discrete outbreaks, and then do rigorous contact tracing.”

But doing so takes intelligent, rapidly adaptive work by health officials, and near-total cooperation from the populace. Containment becomes realistic only when Americans realize that working together is the only way to protect themselves and their loved ones.

In interviews with a dozen of the world’s leading experts on fighting epidemics, there was wide agreement on the steps that must be taken immediately.

Those experts included international public health officials who have fought AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, flu and Ebola; scientists and epidemiologists; and former health officials who led major American global health programs in both Republican and Democratic administrations.

Americans must be persuaded to stay home, they said, and a system put in place to isolate the infected and care for them outside the home. Travel restrictions should be extended, they said; productions of masks and ventilators must be accelerated, and testing problems must be resolved.

[…]

Just as generals take the lead in giving daily briefings in wartime — as Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf did during the Persian Gulf war — medical experts should be at the microphone now to explain complex ideas like epidemic curves, social distancing and off-label use of drugs.

The microphone should not even be at the White House, scientists said, so that briefings of historic importance do not dissolve into angry, politically charged exchanges with the press corps, as happened again on Friday.

Instead, leaders must describe the looming crisis and the possible solutions in ways that will win the trust of Americans.

Above all, the experts said, briefings should focus on saving lives and making sure that average wage earners survive the coming hard times — not on the stock market, the tourism industry or the president’s health. There is no time left to point fingers and assign blame.

The next priority, experts said, is extreme social distancing.

If it were possible to wave a magic wand and make all Americans freeze in place for 14 days while sitting six feet apart, epidemiologists say, the whole epidemic would sputter to a halt.

What’s new:

The truth of the first decades of the 21st century, a truth that helped give us the Trump presidency but will still be an important truth when he is gone, is that we probably aren’t entering a 1930-style crisis for Western liberalism or hurtling forward toward transhumanism or extinction.

Instead, we are aging, comfortable and stuck, cut off from the past and no longer optimistic about the future, spurning both memory and ambition while we await some saving innovation or revelation, growing old unhappily together in the light of tiny screens.

Why it matters:

[T]rue dystopias are distinguished, in part, by the fact that many people inside them don’t realize that they’re living in one, because human beings are adaptable enough to take even absurd and inhuman premises for granted.

If we feel that elements of our own system are, shall we say, dystopia-ish — from the reality-television star in the White House to the addictive surveillance devices always in our hands; from the drugs and suicides in our hinterlands to the sterility of our rich cities — then it’s possible that an outsider would look at our decadence and judge it more severely still. [AXIOS]

Cut the drama. The real story of the West in the 21st century is one of stalemate and stagnation.

“…civilization has entered into decadence,” in the classic sense of the word — “a lack of resolution in the face of threats,” with “hints at exhaustion, finality.”

Following in the footsteps of the great cultural critic Jacques Barzun, we can say that decadence refers to economic stagnation, institutional decay and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development. Under decadence, Barzun wrote, “The forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result.” He added, “When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent.” And crucially, the stagnation is often a consequence of previous development: The decadent society is, by definition, a victim of its own success.

Note that this definition does not imply a definitive moral or aesthetic judgment. (“The term is not a slur,” Barzun wrote. “It is a technical label.”) A society that generates a lot of bad movies need not be decadent; a society that makes the same movies over and over again might be. A society run by the cruel and arrogant might not be decadent; a society where even the wise and good can’t legislate might be. A crime-ridden society isn’t necessarily decadent; a peaceable, aging, childless society beset by flares of nihilistic violence looks closer to our definition.

Nor does this definition imply that decadence is necessarily an overture to a catastrophe, in which Visigoths torch Manhattan or the coronavirus has dominion over all. History isn’t always a morality play, and decadence is a comfortable disease: The Chinese and Ottoman empires persisted for centuries under decadent conditions, and it was more than 400 years from Caligula to the actual fall of Rome.

“What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman Empire is not that it finally went smash,” wrote W.H. Auden of that endless autumn, but rather that “it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth, or hope.”

[…]

Close Twitter, log off Facebook, turn off cable television, and what do you see in the Trump-era United States? Campuses in tumult? No: The small wave of campus protests, most of them focused around parochial controversies, crested before Trump’s election and have diminished since. Urban riots? No: The post-Ferguson flare of urban protest has died down. A wave of political violence? A small spike, maybe, but one that’s more analogous to school shootings than to the political clashes of the 1930s or ’60s, in the sense that it involves disturbed people appointing themselves knights-errant and going forth to slaughter, rather than organized movements with any kind of concrete goal.

The madness of online crowds, the way the internet has allowed the return of certain forms of political extremism and the proliferation of conspiracy theories — yes, if our decadence is to end in the return of grand ideological combat and street-brawl politics, this might be how that ending starts.

But our battles mostly still reflect what Barzun called “the deadlocks of our time” — the Kavanaugh Affair replaying the Clarence Thomas hearings, the debates over political correctness cycling us backward to fights that were fresh and new in the 1970s and ’80s. The hysteria with which we’re experiencing them may represent nothing more than the way that a decadent society manages its political passions, by encouraging people to playact extremism, to re-enact the 1930s or 1968 on social media, to approach radical politics as a sport, a hobby, a kick to the body chemistry, that doesn’t put anything in their relatively comfortable late-modern lives at risk.

Complaining about decadence is a luxury good — a feature of societies where the mail is delivered, the crime rate is relatively low, and there is plenty of entertainment at your fingertips. Human beings can still live vigorously amid a general stagnation, be fruitful amid sterility, be creative amid repetition. And the decadent society, unlike the full dystopia, allows those signs of contradictions to exist, which means that it’s always possible to imagine and work toward renewal and renaissance.

‘…thinking seriously about how to rebuild after DT leaves office, and how to create a political life that exists outside him and is not dependent on him as its source of terrible gravity.’

[full read]

DT is the third president in our nation’s history to be impeached. [Articles I & II]

“Dawn Whitson, a shelter resident making $12 an hour as a hotel receptionist, said she wanted to know why the city was spending potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight the suit instead of putting the money toward more shelter beds or homeless services.”

NYTimes

BOISE, Idaho — During a recent mayoral debate at a Boise homeless shelter, after disposing of icebreakers like the candidates’ favorite Metallica album, the moderator turned to something more contentious: a decade-old lawsuit, now a step away from the Supreme Court. The case, Boise v. Martin, is examining whether it’s a crime for someone to sleep outside when they have nowhere else to go.

The suit arose when a half-dozen homeless people claimed that local rules prohibiting camping on public property violated the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment. The plaintiffs prevailed at the appellate level last year, putting the city at the center of a national debate on how to tackle homelessness. Now Boise — after hiring a powerhouse legal team that includes Theodore B. Olson and Theane Evangelis of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher — has asked the Supreme Court to take the case, a decision that could come within days.

Nobody at Interfaith Sanctuary, a shelter for 164 with bunk beds in neat rows, needed a primer. They had been talking about it for weeks. Before the debate, Dawn Whitson, a shelter resident making $12 an hour as a hotel receptionist, said she wanted to know why the city was spending potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight the suit instead of putting the money toward more shelter beds or homeless services.

In the course of the one-hour event organized by the shelter, the two candidates, competing in a runoff election on Tuesday, heard plenty more about the issue. One person said there was a misconception that all homeless people are drug addicts. A veteran said he had $771 left over from his disability check each month but couldn’t find a room for less than $500, and asked what he was supposed to do.

Even before the answers, everyone knew who the room was for. Lauren McLean, the City Council president and top vote-getter in an inconclusive November election, opposes the city’s quest for leeway in policing the homeless. She says the solution should come from tackling poverty.

“Each of us, no matter our situation, has to sleep,” she said. “We need more beds. We need to create homes for our residents.”

Her opponent, Mayor David Bieter, seeking his fifth term, was unapologetic about fighting the lawsuit, despite the shelter crowd. Echoing the position of various Western cities that support Boise’s stand, Mr. Bieter argued that the ability to issue citations for sleeping outside is a little-used but necessary tool to keep homelessness in check.

“I’m really concerned when I see Seattle or Portland or San Francisco,” he said. “I go there and I see a city that’s overwhelmed by the problem, and people tell me all the time, ‘Don’t allow us to be like those other cities.’”

On the surface, Boise, a city of about 230,000 whose modest downtown does little to obscure the mountain views, is an odd point of origin for such a debate. Its annual homeless counthas found about 50 to 100 unsheltered people for the past seven years. A drive around town turned up a handful of people sleeping outside, a far cry from the blocklong tent cities in California.

But the city’s decision to appeal Boise v. Martin has elevated homelessness to a focus of an increasingly ugly campaign. Third-party mailers have put Ms. McLean’s picture next to a homeless encampment with the words, “Lauren McLean’s Future Boise.” She recently posted on Facebook that someone in a pickup truck was putting tents and sleeping bags next to “McLean for Boise” yard signs.

The city’s relatively modest homeless problem is cited by both candidates to bolster their positions. Each is essentially campaigning on the idea that rapid growth needn’t produce streets of destitution as it has in California — but the two diverge on the role that law enforcement should play.

To Mr. Bieter, the homeless crises in Los Angeles and San Francisco prove that the city’s power to issue citations and shoo sleeping people off sidewalks is needed to prevent larger camps from forming.

Ms. McLean calls for a different approach. “I think other cities got to the point where it was too late,” she said in an interview. “So let’s say right now we’re actually going to get to work to prevent homelessness instead of hanging our hat on getting the right to ticket people.”

The road to the Supreme Court’s doorstep began in the office of Howard Belodoff, a Boise civil rights lawyer. In 2009, after a local shelter closed, Mr. Belodoff filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of six homeless men and women who had been cited for violating city ordinances that prohibit sleeping on public property. Most of the plaintiffs were prosecuted and pleaded guilty, with the exception of Robert Martin, whose case was dismissed.

Mr. Martin and the other plaintiffs subsequently filed suit challenging the constitutionality of the city’s ordinances. The case was litigated for several years before being appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Last year, in a decision that reverberated across the West Coast, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional to cite someone for sleeping outdoors if there wasn’t any shelter available.

In August, Boise formally asked the Supreme Court to hear the case. While the Ninth Circuit has described its decision as “narrow,” the city’s petition portrays it as anything but, using words like “vast,” “far-reaching” and “catastrophic” to depict a picture of mass confusion and lawlessness arising from the court’s ruling. The filing goes on to say that the Ninth Circuit’s ruling could also imperil a host of other public health laws “such as those prohibiting public defecation and urination.”

“Public encampments, now protected by the Constitution under the Ninth Circuit’s decision, have spawned crime and violence, incubated disease and created environmental hazards that threaten the lives and well-being both of those living on the streets and the public at large,” it declares.

In an interview, Ms. Evangelis, from Gibson Dunn, said: “I don’t think that fighting for someone’s right to live and die in squalor is helping.”

In response, lawyers for the plaintiffs, quoting an earlier Ninth Circuit decision, argue that the court’s ruling in the Boise case merely “reflects the ought-to-be uncontroversial principle that a person may not be charged with a crime for engaging in activity that is simply ‘a universal and unavoidable consequence of being human.’”

Dozens of cities have filed briefs backing Boise’s position, saying that they are confused as to how broadly the Ninth Circuit ruling applies and that the decision has impeded enforcement of basic health and safety laws. In some cases, the cities contend, the decision has actually made it harder to build housing meant for the homeless.

Among Boise’s allies is Los Angeles, which has passed more than $1 billion in bonds for permanent supportive housing but has found steep neighborhood resistance. Mike Feuer, the Los Angeles city attorney, said the Ninth Circuit decision raised as many questions as it answered. For instance, to determine whether or not is in compliance with the ruling, does the city have to constantly count how many beds there are and compare it to the homeless population? Can Los Angeles prohibit sleeping in sensitive locations, such as next to new homeless shelters?

“The language, rather than citing clear principles where constitutional questions are at stake, makes local jurisdictions vulnerable to lawsuits as they struggle to achieve a balance between the legitimate rights and interests of homeless people and the legitimate rights and interests of other residents and businesses,” he said.

Whatever happens in the Boise mayor’s race, Boise v. Martin is far enough along that its fate now rests with the Supreme Court: Even if she is elected mayor, Ms. McLean said, she has no plans to withdraw from the case. “The case is moving forward — that ship has sailed,” she said. “I just still maintain that we can do this without ticketing folks and moving them into the criminal justice system, which will make it harder to find shelter, home and work.”

#

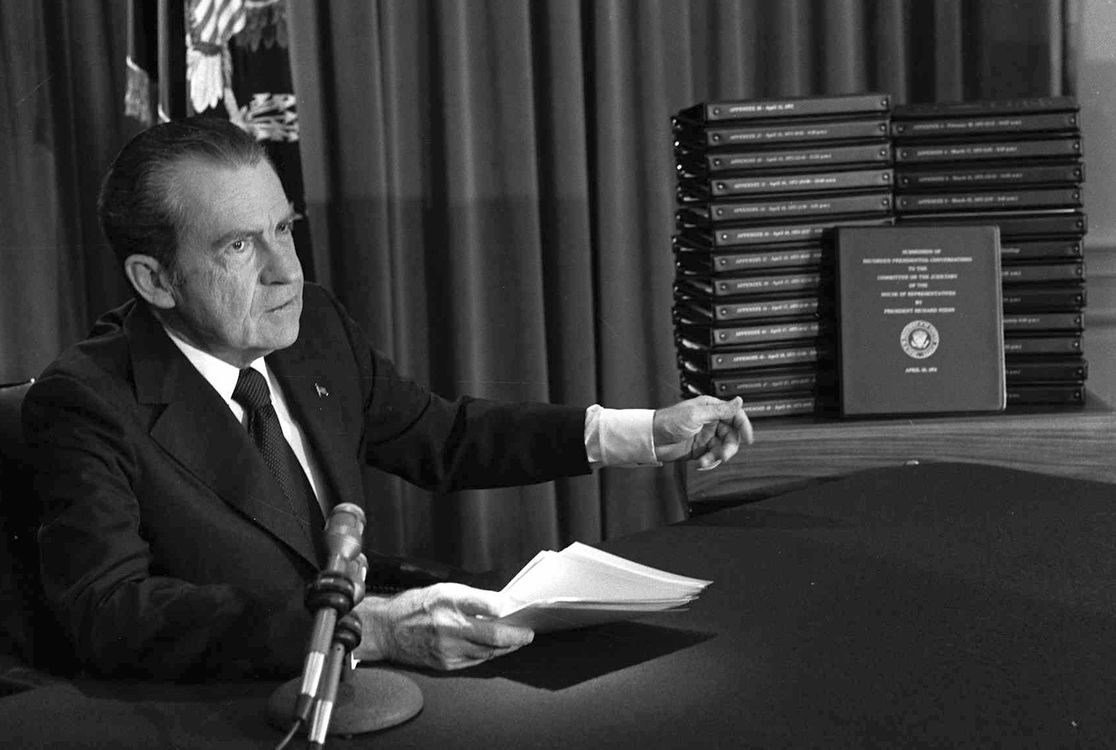

| A lesson from 45 years ago… |

On April 29, 1974, President Richard M. Nixon points to the transcripts of the White House tapes after he announced during a nationally-televised speech that he would turn over the transcripts to House impeachment investigators. Photo: AP

“As a junior aide in President Richard Nixon’s White House, I saw congressional oversight and investigation command immensely greater power and respect than it does today,” Jonathan C. Rose — special assistant to Nixon from 1971 to 1973, and associate deputy attorney general from 1973 to 1975 — writes in The Atlantic. “As evidence implicating the White House mounted, the administration displayed no inclination toward negotiation or accommodation with the Senate Watergate Committee. On March 15, 1973, Nixon issued an edict asserting executive privilege, declaring that White House aides and papers were entirely off limits to the committee. If the committee desired to press the issue, the president said, it could pursue a contempt prosecution through the courts.

“Pressed for his reaction, [Senate Watergate Committee Chairman Sam] Ervin said Nixon’s position was ‘executive poppycock, akin to the divine right of kings.’ Ervin declared that his committee had no intention of submitting to the suggested judicial delays, but would instead utilize the Senate’s sergeant at arms to arrest any recalcitrant White House aide, bring him to the bar of the Senate for trial, and ultimately compel him to testify.

“As damaging revelations continued to mount and the stigma of cover-up gathered strength, the White House floated trial balloons, offering the Watergate Committee possible closed-door interviews with White House aides. …

“By mid-April 1973, Nixon’s resistance to testimony by White House aides had collapsed, and a number of them testified. This testimony disclosed the White House taping system and confirmed the existence of tapes. Those disclosures ultimately led to Nixon’s departure from office.”

-AXIOS

|

Please read.

“By then, she was beginning to wonder if this system was broken — if, in fact, a presidential campaign was designed to keep outsiders out, which is the opposite of democracy. “People would say, ‘You’re out of your depth,’ ” she said. “I feel I’m in my depth. A deeper conversation is in the depth. I’m the only one who mentioned American foreign policy in Latin America. I’m the only one who mentioned that our health care system is basically a sickness care system. I’m the only one who mentioned what Donald Trump is actually doing, collectivizing fear, and what it will take to override that. So was I out of my depth? Or is the conversation that was being promoted there not chronically superficial? And any conversation which is in fact of depth is made to appear silly?”

NY TIMES

9.3.19

FEATURE

he first problem with Marianne Williamson is what do you call her. The other candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination lead with their impressive elected titles: “Governor,” “Senator,” “Mayor.” She’s a lot of fancy things herself: a faith leader, a spiritual guide on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” a New Age guru. But she knows that when people use terms like that outside the nearly $10 billion self-help industry, where a person like her is sought, they mean it to dismiss her. So while everyone else has dignified titles of experience to stick onto their lapels and on chyrons for the debates (all except Andrew Yang, who is a “former tech executive,” but it doesn’t really matter what he’s called because he’s running on a platform of giving each American $1,000 per month for life), she settled on, simply, “author.” Author is accurate, if not the whole story.

Williamson is also a politician now, and on the weekend after Independence Day, she was doing what politicians do, which is visit citizens gathered at people’s homes (and on peach farms and at ice-cream socials) and make a case to the American people, one group of interested voters at a time. There she stood, tiny and regal, on the breathtaking porch of someone else’s breathtaking home in New Castle, N.H., right on the river, giving a civics lesson not about her specific policies; those were all on her website, under the label “The Issues Aren’t Always the Issue.” She was talking about how she could beat Donald Trump.

She told the crowd the story of David and Goliath, about how she’s going to be like David and defeat Trump with just a slingshot. “We’re going to get him right between the eyes,” she said. “David got Goliath in his third eye, where he wasn’t prepared — where he had no defense.” The third eye, she explained, was Trump’s ego and his inability to see clearly. It was his instinct to divide the country along the old fault lines of hatred and greed and apathy toward suffering. The slingshot, which was small but mighty, was, of course, love. Love was her entire platform. She believed that if we were to look at all the country’s problems through the prism of love, we could undo everything from poverty to climate change to the immigration crisis.

Everyone talked about the issues. She wanted to talk about how we could have prevented these issues — how we could undo them if we got to the root of all these problems. “People who are so depressed because they don’t know how they’re going to ever get out of this college loan. People who were so depressed because they don’t know what’s going to happen if they get sick. People who are so depressed because they don’t know how they’re going to send their kids to college. People who are so depressed because they’re so afraid that their child is going to get picked up by the policemen and there’s absolutely nothing they can do no matter how much they try to raise a good kid and even have a good kid. People working with refugees, people working with immigrants, veterans, traumatized children, drug addicts. Everything I just mentioned has the fingerprints of public policy — irresponsible, reckless public policy.”

She has a patrician, mid-Atlantic accent that she has taped over her Texan accent — she was raised in Houston. She talks so fast, like a movie star from the ’40s, no hesitations, as if the thoughts came to her fully formed with built-in metaphors, or sometimes just as straight-up metaphors in which the actual is never fully explained. (“Am I pushing the river? Am I going with the flow? Am I trying to make something happen, or am I in some way being pushed from behind?”) She is prone to exasperated explosions of unassailable logic (“The best car mechanic doesn’t necessarily know the road to Milwaukee!”). A thing she loves to say is: “I’m not saying anything you don’t already know.” This is the self-help magic ne plus ultra, a spoken thing that rings inside your blood like the truth, a thing you knew all along, like ruby slippers you were wearing the whole time.

She finished her speech in New Hampshire to great applause and asked for questions, but nobody wanted to know how “a politics of love,” as she called it, would handle, say, President Vladimir Putin’s annexing Crimea, or how it would prevent a mass shooting, which were things she had thought about deeply and had specific and elaborate plans for. They didn’t want to know about her Department of Children and Youth or her Department of Peace. No, they wanted self-help. A woman raised her hand and said she didn’t know what to do about her trauma and her rage these days — how she couldn’t find forgiveness for the people who voted for Trump, even though those people weren’t exactly asking for it. “It’s like I’ve been infected,” the woman said. “How do I manage that?”

Williamson told her she has no time for people traumatized by the election. She asked the crowd to consider the trauma of the suffragists, who were force-fed through tubes when they were put into jails. She asked them to consider the trauma of the black protesters who took their lives in their hands when they marched in Selma. And she has even less time for people who think that anger is a productive emotion. Anger, she has said, is the white sugar of activism. It’s a good rush, but it doesn’t provide nourishment.

“Your personal anger depletes you,” she told the woman, her X-Acto-knife jaw jutted outward and her head high. “Trump isn’t the problem. The system of complacency is the problem.” The problem was apathy toward the entire revolutionary nature of this country — the radicalism of the Constitution, the power that it gave every single American. “Don’t hate Trump,” she beseeched the woman. “Love democracy.”

Self-help made Marianne Williamson, who is 67, famous. It was the number of selves she had helped in her 38-year career, and after selling over three million books, that made her feel she was qualified to take on the world’s problems. Rather than solving suffering one theater full of self-selecting audience members at a time, she could focus on alleviating suffering on a much larger scale. She was not concerned by the scoffings about her inexperience. Every time I heard her speak, she said: “I challenge the idea that only people whose careers have been entrenched for decades in the limitations of the mind-set that drove us into this ditch are the only ones we should consider qualified to take us out of the ditch.”

NYTIMES

WASHINGTON — Extensive work was well underway on a new $20 bill bearing the image of Harriet Tubman when Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced last month that the design of the note would be delayed for technical reasons by six years and might not include the former slave and abolitionist.

Many Americans were deeply disappointed with the delay of the bill, which was to be the first to bear the face of an African-American. The change would push completion of the imagery past DT’s time in office, even if he wins a second term, stirring speculation that Mr. Trump had intervened to keep his favorite president, Andrew Jackson, a fellow populist, on the front of the note.

But Mr. Mnuchin, testifying before Congress, said new security features under development made the 2020 design deadline set by the Obama administration impossible to meet, so he punted Tubman’s fate to a future Treasury secretary.

In fact, work on the new $20 note began before DT took office, and the basic design already on paper most likely could have satisfied the goal of unveiling a note bearing Tubman’s likeness on next year’s centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

That preliminary design was completed in late 2016.

A spokeswoman for the bureau, Lydia Washington, confirmed that preliminary designs of the new note were created as part of research that was done after Jacob J. Lew, President Barack Obama’s final Treasury secretary, proposed the idea of a Tubman bill.

The development of the note did not stop there.

A current employee of the bureau, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter, personally viewed a metal engraving plate and a digital image of a Tubman $20 bill while it was being reviewed by engravers and Secret Service officials as recently as May 2018. This person said that the design appeared to be far along in the process.

Within the bureau, this person said, there was a sense of excitement and pride about the new $20 note.

But the Treasury Department, which oversees the engraving bureau, decided that a new $20 bill would not be made public next year. Current and former department officials say Mr. Mnuchin chose the delay to avoid the possibility that Mr. Trump would cancel the plan outright and create even more controversy.

In an interview last week, Mr. Mnuchin denied that the reasons for the delay were anything but technical.

“Let me assure you, this speculation that we’ve slowed down the process is just not the case,” Mr. Mnuchin said, speaking on the sidelines of the G-20 finance ministers meeting in Japan.

The Treasury secretary reiterated that security features drive the change of the currency and rejected the notion that political interference was at play. He declined to say if he believed his predecessor had tried to politicize the currency.

Interagency, including the Secret Service and others and B.E.P., that are all career officials that are focused on this,” he said, referring to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. “They’re working as fast as they can.”

Monica Crowley, a spokeswoman for Mr. Mnuchin, added that the release into circulation of the new $20 note remained on schedule with the bureau’s original timeline of 2030. She did not, however, say that the bill would feature Tubman.

“The scheduled release (printing) of the $20 bill is on a timetable consistent with the previous administration,” she said in a statement.

But building the security features of a new note before designing its images struck some as curious. Larry E. Rolufs, a former director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, said that because the security features of a new note are embedded in the imagery, they normally would be created simultaneously.

“It can be done at the same time,” said Mr. Rolufs, who led the bureau from 1995 to 1997. “You want to work them together.”

The process of developing American currency is painstaking, done by engravers who spend a decade training as apprentices. People familiar with the process say that engravers spend months working literally upside down and backward carving the portraits of historical figures into the steel plates that eventually help create cash. Often, multiple engravers will attempt different versions of the portraits, usually based on paintings or photographs, and ultimately, the Treasury secretary chooses which one will appear on a note.

Mr. Rolufs said that because of the complexity of creating new currency, circulating a new note design by next year was ambitious. He also acknowledged that making major changes to the money is an invitation for backlash.

“For the secretary to change the design of the notes takes political courage,” he said. “The American people don’t like their currency messed with.”

As a presidential candidate, Mr. Trump called the decision to replace Jackson, who was a slave owner, with Tubman “pure political correctness.” An overhaul of the Treasury Department’s website after Mr. Trump took office removed any trace of the Obama administration’s plans to change the currency, signaling that the plan might be halted.

Within Mr. Trump’s Treasury Department, some officials complained that Mr. Lew had politicized the currency with the plan and that the process of selecting Tubman, which included an online poll among other forms of feedback, was not rigorous or reflective of the country’s desires.

The uncertainty has renewed interest in the matter. This week, Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland, where Tubman was born, wrote a letter to Mr. Mnuchin urging him to find a way to speed up the process.

“I hope that you’ll reconsider your decision and instead join our efforts to promptly memorialize Tubman’s life and many achievements,” wrote Mr. Hogan, a Republican.

And last week, a group of House Democrats demanded that the Treasury secretary provide specific information about the security concerns that were impeding the currency redesign.

At the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which offers tours and an exhibit on the history of the currency, some visitors said they preferred tradition, while others were seeking change.

“For me, it’s not important enough to spend the money to change it,” said Jeff Dunyon, who was visiting Washington from Utah this week. “There are other ways to honor her.”

Charnay Gima, a tourist from Hawaii, had just finished a tour when she pulled aside a guide to ask a question that was bothering her. She wanted to know what became of the plan to make Tubman the face of the $20 bill.

To Ms. Gima’s dismay, there was no sign of Tubman in any of the bureau’s exhibits. The plan was scrapped, she was told, for political reasons.

“It’s kind of sad,” said Ms. Gima, who is black. “I was really looking forward to it because it was finally someone of color on the bill who paved the way for other people.”

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/05/22/when-every-day-is-memorial-day/?_r=0

NYTIMES

‘Use of the devices among middle- and high school students tripled from 2013 to 2014, according to federal data released on Thursday, bringing the share of high school students who use them to 13 percent — more than smoke traditional cigarettes. The sharp rise, together with a substantial increase in the use of hookah pipes, led to 400,000 additional young people using a tobacco product in 2014…’