Spanish Flu

COVID COMPASSION

May 9, 2020As individuals and communities, we can respond with justice and compassion, or we can double down on the pursuit of accumulation and power, with no more than a return to business as usual.

-Father Richard Rohr

Center for Action & Contemplation

‘The pandemic has severely attacked vulnerable communities of color, including tribal communities whose members may not have access to adequate health care nor clean water, we turn to a young voice from the Navajo Nation.’

[Desperado Philosophy]

Aware that the pandemic has severely attacked vulnerable communities of color, including tribal communities whose members may not have access to adequate health care nor clean water, we turn to a young voice from the Navajo Nation (Diné), Alastair Lee Bitsóí, relayed from the pages of the Navajo Times. Excerpts below, with images from the studio of Tony Abeyta.

https://desperadophilosophy.net/2020/05/09/nature-in-control/amp/?__twitter_impression=true

[Investigative, compassionate journalism. -dayle]

‘Life expectancy gap between black & white Chicagoans, largest in the country: Structural racism, concentrated poverty, economic exploitation & chronic stress cause what’s known as biological weathering.’

ProPublica

ProPublica is an independent, non-profit newsroom that produces investigative journalism in the public interest. THE FIRST 100 COVID-19 Took Black Lives First. It Didn't Have To.

“We’re not going to reverse this in a moment, overnight, but we have to say it for what it is and move forward decisively as a city, and that’s what we will do,” she said. “This is about health care accessibility, life expectancy, joblessness and hunger.”

ProPublica’s reporting also revealed other patterns, factors that could — and should — have been addressed and which almost certainly exist in other communities experiencing similar disparities. Even though many of these victims had medical conditions that made them particularly susceptible to the virus, they didn’t always get clear or appropriate guidance about seeking treatment. They lived near hospitals that they didn’t trust and that weren’t adequately prepared to treat COVID-19 cases. And perhaps most poignantly, the social connections that gave their lives richness and meaning — and that played a vital role in helping them to navigate this segregated city that can at times feel hostile to black residents — made them more likely to be exposed to the virus before its deadly power became apparent.

The city [Chicago] announced the Racial Equity Rapid Response Team in partnership with West Side United, with a goal to “bring a hyper local public health strategy to targeted communities.” In the weeks since, the team has held tele-town halls, delivered thousands of door hangers and postcards with targeted information, and distributed 60,000 masks for residents in the predominantly black communities of Austin, Auburn Gresham and South Shore.

https://features.propublica.org/chicago-first-deaths/covid-coronavirus-took-black-lives-first/

So much new & good is going to come from this. We can stop deluding ourselves that our current way of organizing our society is either sane or even survivable! That had to come first in order to rock us to our core, to humble us. Now we’ll be open to new ideas in a whole new way.

-Marianne Williamson

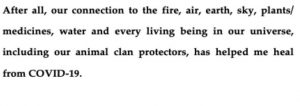

A poster from 1918 asks Chicagoans to self-quarantine if they have symptoms of the flu. For more, see “Don’t Spit! Pandemic Posters Through the Years.” (Courtesy National Library of Medicine)

The Atlantic

Disaster Studies

Pandemics Leave Us Forever Altered

by Charles C. Mann

What history can tell us about the long-term effects of the coronavirus

Just a few decades after the pandemic, American-history textbooks by the distinguished likes of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Richard Hofstadter, Henry Steele Commager, and Samuel Eliot Morison said not a word about it. The first history of the 1918 flu wasn’t published until 1976—I drew some of the above from it. Written by the late Alfred W. Crosby, the book is called America’s Forgotten Pandemic.

Americans may have forgotten the 1918 pandemic, but it did not forget them. Garthwaite matched NHIS respondents’ health conditions to the dates when their mothers were probably exposed to the flu. Mothers who got sick in the first months of pregnancy, he discovered, had babies who, 60 or 70 years later, were unusually likely to have diabetes; mothers afflicted at the end of pregnancy tended to bear children prone to kidney disease. The middle months were associated with heart disease.

Other studies showed different consequences. Children born during the pandemic grew into shorter, poorer, less educated adults with higher rates of physical disability than one would expect. Chances are that none of Garthwaite’s flu babies ever knew about the shadow the pandemic cast over their lives. But they were living testaments to a brutal truth: Pandemics—even forgotten ones—have long-term, powerful aftereffects.

[…]

The convulsive social changes of the 1920s—the frenzy of financial speculation, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the explosion of Dionysian popular culture (jazz, flappers, speakeasies)—were easily attributed to the war, an initiative directed and conducted by humans, rather than to the blind actions of microorganisms. But the microorganisms likely killed more people than the war did. And their effects weren’t confined to European battlefields, but spread across the globe, emptying city streets and filling cemeteries on six continents.

Unlike the war, the flu was incomprehensible—the influenza virus wasn’t even identified until 1931. It inspired fear of immigrants and foreigners, and anger toward the politicians who played down the virus. Like the war, influenza (and tuberculosis, which subsequently hit many flu sufferers) killed more men than women, skewing sex ratios for years afterward. Can one be sure that the ensuing, abrupt changes in gender roles had nothing to do with the virus?

[…]

To save themselves from the disease, scared Europeans sought favor from the heavens, most famously taking off their clothes in groups and striking one another with whips and sticks. Images of half-nude flagellants have, since Monty Python, become a comic staple. Far less comical was the accompanying flood of anti-Semitic violence. As it spread through Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, and the Low Countries, it left behind a trail of beaten cadavers and burned homes.

Absent the diseases, it is difficult to imagine how small groups of poorly equipped Europeans at the end of very long supply chains could have survived and even thrived in the alien ecosystems of the Americas. “I fully support banning travel from Europe to prevent the spread of infectious disease,” the Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle remarked after President Trump announced his plan to do this. “I just think it’s 528 years too late.”

For Native Americans, the epidemic era lasted for centuries, as did its repercussions. Isolated Hawaii had almost no bacterial or viral disease until 1778, when the islands were “discovered” by Captain James Cook. Islanders learned the cruel facts of contagion so rapidly that by 1806, local leaders were refusing to allow European ships to dock if they had sick people on board. Nonetheless, Hawaii’s king and queen traveled from their clean islands to London, that cesspool of disease, arriving in May 1824. By July they were dead—measles.

Later it occurred to me that a possible legacy of Hong Kong’s success with SARS is that its citizens seem to put more faith in collective action than they used to. I’ve met plenty of people there who believe that the members of their community can work together for the greater good—as they did in suppressing SARS and will, with luck, keep doing with COVID-19. It’s probably naive of me to hope that successfully containing the coronavirus would impart some of the same faith in the United States, but I do anyway.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/pandemics-plagues-history/610558/

1918 & 2020

April 8, 2020Credit…via Library of Congress, via Associated Press

Why Is This Happening with Chris Hayes

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/msnbc/why-is-this-happening

The Last Great Pandemic with John M. Barry

‘What did we learn from the last great pandemic? You don’t have to dig deep into the 1918 influenza before finding eerie similarities to today – be it the White House downplaying the severity of the virus or the social distancing measures recommended by public health officials. Author John M. Barry’s meticulously researched account of the 1918 pandemic in his book “The Great Influenza” was so affecting that it inspired then President George W. Bush to develop a comprehensive pandemic plan after reading it. There’s no one better to discuss the similarities and differences to what played out a century ago – and the far reaching reverberations this moment will have – than John M. Barry.’

“The failure of the government in this is incomprehensible.

We don’t have a plan.”

-John M. Barry

#MustListen #COVID19US #withpod

NYTimes

The Single Most Important Lesson From the 1918 Influenza

Cultural Corona

March 17, 2020“Without trust and global solidarity we will not be able to stop the coronavirus epidemic we will not be able to stop the coronavirus epidemic, and we are likely to see more such epidemics in the future. But every crisis is also an opportunity.

-Yuval Noah Harari

Noah Harari is a historian, philosopher and the bestselling author of Sapiens, Homo Deusand 21 Lessons for the 21st Century.

Perhaps the most important thing people should realize about such epidemics, is that the spread of the epidemic in any country endangers the entire human species. This is because viruses evolve. Viruses like the corona originate in animals, such as bats. When they jump to humans, initially the viruses are ill-adapted to their human hosts. While replicating within humans, the viruses occasionally undergo mutations. Most mutations are harmless. But every now and then a mutation makes the virus more infectious or more resistant to the human immune system – and this mutant strain of the virus will then rapidly spread in the human population. Since a single person might host trillions of virus particles that undergo constant replication, every infected person gives the virus trillions of new opportunities to become more adapted to humans. Each human carrier is like a gambling machine that gives the virus trillions of lottery tickets – and the virus needs to draw just one winning ticket in order to thrive.

(Original Caption) Photo shows a scene in the influenza Camp at Lawrence, Maine, where patients are given fresh air treatment. this extreme measure was hit upon as the best way of curbing the epidemic. Patients are required to live in these camps until cured.

As you read these lines, perhaps a similar mutation is taking place in a single gene in the coronavirus that infected some person in Tehran, Milan or Wuhan. If this is indeed happening, this is a direct threat not just to Iranians, Italians or Chinese, but to your life, too. People all over the world share a life-and-death interest not to give the coronavirus such an opportunity. And that means that we need to protect every person in every country.

[…]

Today humanity faces an acute crisis not only due to the coronavirus, but also due to the lack of trust between humans. To defeat an epidemic, people need to trust scientific experts, citizens need to trust public authorities, and countries need to trust each other. Over the last few years, irresponsible politicians have deliberately undermined trust in science, in public authorities and in international cooperation. As a result, we are now facing this crisis bereft of global leaders that can inspire, organize and finance a coordinated global response.

[…]

What does this history teach us for the current Coronavirus epidemic?

First, it implies that you cannot protect yourself by permanently closing your borders. Remember that epidemics spread rapidly even in the Middle Ages, long before the age of globalization. So even if you reduce your global connections to the level of England in 1348 – that still would not be enough. To really protect yourself through isolation, going medieval won’t do. You would have to go full Stone Age. Can you do that?

Secondly, history indicates that real protection comes from the sharing of reliable scientific information, and from global solidarity. When one country is struck by an epidemic, it should be willing to honestly share information about the outbreak without fear of economic catastrophe – while other countries should be able to trust that information, and should be willing to extend a helping hand rather than ostracize the victim. Today, China can teach countries all over the world many important lessons about coronavirus, but this demands a high level of international trust and cooperation.

[…]

In this moment of crisis, the crucial struggle takes place within humanity itself. If this epidemic results in greater disunity and mistrust among humans, it will be the virus’s greatest victory. When humans squabble – viruses double. In contrast, if the epidemic results in closer global cooperation, it will be a victory not only against the coronavirus, but against all future pathogens.

https://time.com/5803225/yuval-noah-harari-coronavirus-humanity-leadership/

VOX

Scientists warn we may need to live with social distancing for a year or more

Researchers say we face a horrible choice: practice social distancing for months or a year, or let hundreds of thousands die.

Life in America — and in many countries around the world — is changing drastically. We’re physically distanced from our favorite people, we’re avoiding our favorite public places, and many are financially strained or out of work. The response to the Covid-19 pandemic is infiltrating every aspect of life, and we’re already longing for it to end. But this fight may not end for months or a year or even more.

We’re in this because public health experts believe social distancing is the best way to prevent a truly horrific crisis: perhaps hundreds of thousands or more if our health care system is overwhelmed with severe Covid-19 cases, people who require ventilators and ICU beds that are now growing limited in supply.

“Some may look at [the guidelines] … and say, well, maybe we’ve gone a little bit too far,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a member of the White House coronavirus task force, at a Monday White House press conference. “They were well thought out. And the thing that I want to reemphasize … when you’re dealing with an emerging infectious diseases outbreak, you are always behind where you think you are if you think that today reflects where you really are.”

How long, then, until we’re no longer behind and are winning the fight against the novel coronavirus? The hard truth is that it may keep infecting people and causing outbreaks until there’s a vaccine or treatment to stop it.

“I think this idea … that if you close schools and shut restaurants for a couple of weeks, you solve the problem and get back to normal life — that’s not what’s going to happen,” says Adam Kucharski, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of The Rules of Contagion, a book on how outbreaks spread. “The main message that isn’t getting across to a lot of people is just how long we might be in this for.”

Ugh, whyyyyy???

The reason we may be in for an extended period of disruption, Kucharski says, is that the main thing that seems to be working right now to fight this pandemic is severe social distancing policies.

Drop those measures — allow people to congregate in big groups again — while the virus is still out there, and it can start new outbreaks that gravely threaten public health, particularly the older and chronically ill people, those most vulnerable to severe illness. “There’s no way [the virus] is going to go away in the next few weeks,” he says.

The way things are looking now, we’ll need something to stop the virus to truly end the threat. That’s either a vaccine (there are some now entering clinical trials but it could be a year before they are approved) or herd immunity. This is when enough people have contracted the virus, and have become immune to it, to slow its spread.

Herd immunity is not guaranteed. Currently it’s unclear if, after a period of months or years, a person can lose their immunity and become reinfected with the virus (which would make achieving herd immunity more difficult). Also, herd immunity will come at the cost of millions of people becoming infected, and possibly millions of people dying.

A new scientific report stresses: Only the most severe distancing measures can prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths

A sobering new report from the COVID-19 Response Team at the Imperial College of London underscores the need to keep social distancing measures in place for a long period.

It outlines two scenarios for combating the spread of the outbreak. One is mitigation, which focuses on “slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread.” Another is suppression, “which aims to reverse epidemic growth.”

In their analysis, isolation of confirmed cases and quarantine of older adults without social distancing would still result in hundreds of thousands of deaths, and an “eight-fold higher peak demand on critical care beds over and above the available surge capacity in both [Great Britain] and the US.”

(Remember, all projections of possible deaths come with uncertainty and are greatly dependent on how we respond. Estimates can change based on variables that are not quite yet understood: like the role kids play in transmitting the virus, and the potential for the virus to show seasonal effects.)

Bars and restaurants will become takeout-only, and businesses from movie theaters and casinos to gyms and beyond will be shuttered throughout New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, agrees that the social distancing measures might need to be in place for at least months. “I don’t think people are prepared for that and I am not certain we can bear it,” she writes in an email. “I have no idea what political leaders will decide to do. To me, even if this is needed, it seems unsustainable.” She adds that she might just be feeling pessimistic, but “it’s really hard for me to imagine this country staying home for months.”

“Once things get better, we will have to take a step-wise approach toward letting up on these measures and see how things go to prevent things from getting worse again,” says Krutika Kuppalli, an infectious disease physician and Emerging Leader in Biosecurity fellow at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

We also don’t know how long we’re in for because we don’t know how bad the outbreak is in the US — due to the lack of testing.

It’s okay to be upset by all of this. And there are still a lot of unknowns about this virus, and how it will all play out. Perhaps the worst will spare us. But we still need to prepare for it and tap into our resiliency. Life may feel very hard and very stressful over the next several months. It’s a real burden, and you don’t have to like it. But know: This pandemic will end eventually. What we don’t yet know is when.

“Although we may have to be physically apart… we can come together in ways we never have before”

WHO chief Dr Tedros says to overcome the coronavirus pandemic the “spirit of human solidarity must become even more infectious than the virus”

‘How Can I Make You Care?’ BuzzFeed Reporter & Idaho Native On Culture & Coronavirus

Molly Wampler

Anne Helen Petersen is a senior culture writer at BuzzFeed News, She’s based in Montana. Petersen has been covering the culture of the coronavirus, specifically how Americans got to this point in the crisis and why so many of us are having a hard time convincing loved ones to care about this pandemic.

Her recent articles (How Millennials Are Talking To Their Boomer Relatives About The Coronavirus, i don’t know how to make you care about other people) have struck a chord with folks across the country.

She joins Idaho Matters from Montana to talk about what she’s learned reporting on this pandemic in the U.S.

BUZZFEED

How Millennials Are Talking To Their Boomer Relatives About The Coronavirus

The big issue? So many of them don’t want to consider themselves “old” or “vulnerable.”

“There’s a general attitude that we are making a big deal out of nothing. A lot of ‘we deal with the flu every year.’”

There are multiple reasons for this split in approach, from general disposition (preparedness-minded to I’ll-deal-with-it-when-I-have-to) to one’s primary source of news and information. Add in inconsistent messaging from the government and differing “recommendations” from state to state, and it’s easy to understand why people have developed such disparate attitudes about how to proceed in their daily lives. There’s so much that’s unknown about how exactly the spread of the coronavirus will impact the United States, save to observe what’s happened in places that immediately launched extensive testing and quarantine efforts (like Hong Kong and South Korea, both of which have significantly mitigated the disease’s spread) and those that took longer (Italy and Iran).

But here’s what is clear: Even though many people who contract the coronavirus will only experience flulike symptoms, 15% to 20% will develop serious, life-threatening symptoms that demand hospitalization. The statistics from the outbreak in China are incredibly useful in figuring out who’s most at risk: “older adults” (anyone over 60); anyone with heart disease, diabetes, or lung disease; and anyone who is “immunocompromised” (a group that includes about 10 million people in the US, including those with cancer, HIV, and organ transplant recipients).

At this point, the resistance seems to be divided into three overarching areas: misinformation, disidentification, and general stubbornness. Like other types of contemporary misinformation, inaccurate and fake stories about COVID-19 has been spreading most aggressively on Facebook — where, as my colleague Craig Silverman has pointed out, older people are often purposefully targeted by sites and pages trafficking in hyperpartisan rhetoric and straight-up falsehoods.

“My parents and grandparents are on an IV drip of Fox News directly to their brains and believe COVID-19 is a hoax being used as a weapon against the president.”

One person who’s been trying to get his grandfather to take the threat of COVID-19 seriously sent me a screenshot of his latest text, which featured a picture that he’d taken of an image on his own computer. The photo is of a whiteboard, with the dates of previous epidemics, and the caption “POSTED AT A DOCTORS OFFICE TODAY.” (The information in the image has been widely circulating across Facebook and Twitter, but has been officially debunked.) “I don’t think you have to be afraid of the coronavirus,” the grandfather said. “As this post says, diseases appear every year to disrupt the voting process. It is good to be cautious but I believe it’s just another of Satan’s tactics to prevent people from following Jesus.”

[…]

You can also attempt to show, not tell: Show what’s happening in Italy and how the hospitals are overwhelmed, despite full quarantine measures. Explain that if the same thing happens here, they’ll need to be prepared: with meds, with food, with supplies. (Then offer to help them get their hands on those items, as many might be reticent to navigate new systems, like online grocery ordering; one person told me it took an hour to complete her 96-year-old great-grandmother’s order, because she was specifying items like “five green bananas,” but it was worth it: She wasn’t going to the grocery store.)

[…]

Upsetting routine, and replacing it with social isolation for an unspecified amount of time — something that many older people work so hard to counteract — is incredibly difficult to stomach. You can make that easier by promising a whole lot of FaceTiming or video-chatting, and offering to show their friends how to do the same. One woman who works for a public health organization told me that she gradually seeded information to her grandparents and parents, getting them used to the idea of future self-quarantine, before they actually decided to take action.

Empty seats at Goodyear Ballpark in Goodyear, Arizona, March 12. The MLB suspended spring training due to the ongoing threat of the coronavirus outbreak. [Getty]

“My dad was harder,” she explained. “I had to emphasize just how much of a risk he was being to my mom by going out. And eventually I just told him that I know he doesn’t like to overreact, and just generally thinks he’s immune to things, but that I had never really asked him for a favor, and that I was now. I needed him to listen to me, even if he didn’t want to.”

“My mom told me, ‘We are not going to stop living,’ and I said, “That is the point!’”

In some cases, the only thing that will make people take action is others forcing them to. The woman whose immunocompromised mom wouldn’t stop volunteering at the hospital contacted me again today. “The hospital sent all the older volunteers home,” she said. “My mom was a little sad about it, but we had a good conversation about safety and being around for her grandkids.”

Our parents and grandparents have spent their lives being the ones giving us advice and telling us what to do. Reversing that dynamic can feel incredibly unnatural. But even if your parents or grandparents aren’t listening now, they’re going to need you later. Keep trying, keep talking — and, if all else fails, appeal to their parental instincts. “Telling my parents I’m scared has been helpful,” a woman named Mary told me. “They’re way more incentivized to protect me from the fear.” ●

[Important read-full link]

‘…because the government lied, more people died.’

February 28, 2020‘An expert on the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic wrote a piece 2 yrs ago on lessons of why that outbreak was so deadly.

His conclusion: govt officials, desperate to keep morale up during WWI, didn’t tell the truth.

And because the government lied, more people died.’

-Ian Bassin, former associate White House Council

How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America

The toll of history’s worst epidemic surpasses all the military deaths in World War I and World War II combined. And it may have begun in the United States

Although some researchers argue that the 1918 pandemic began elsewhere, in France in 1916 or China and Vietnam in 1917, many other studies indicate a U.S. origin. The Australian immunologist and Nobel laureate Macfarlane Burnet, who spent most of his career studying influenza, concluded the evidence was “strongly suggestive” that the disease started in the United States and spread to France with “the arrival of American troops.” Camp Funston had long been considered as the site where the pandemic started until my historical research, published in 2004, pointed to an earlier outbreak in Haskell County.

Wherever it began, the pandemic lasted just 15 months but was the deadliest disease outbreak in human history, killing between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide, according to the most widely cited analysis. An exact global number is unlikely ever to be determined, given the lack of suitable records in much of the world at that time. But it’s clear the pandemic killed more people in a year than AIDS has killed in 40 years, more than the bubonic plague killed in a century.

The impact of the pandemic on the United States is sobering to contemplate: Some 670,000 Americans died.

A ravaged lung (at the National Museum of Health and Medicine) from a U.S. soldier killed by flu in 1918.(Cade Martin)

We are arguably as vulnerable—or more vulnerable—to another pandemic as we were in 1918. Today top public health experts routinely rank influenza as potentially the most dangerous “emerging” health threat we face. Earlier this year, upon leaving his post as head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tom Frieden was asked what scared him the most, what kept him up at night. “The biggest concern is always for an influenza pandemic…[It] really is the worst-case scenario.” So the tragic events of 100 years ago have a surprising urgency—especially since the most crucial lessons to be learned from the disaster have yet to be absorbed.

Against this background, while influenza bled into American life, public health officials, determined to keep morale up, began to lie.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/