NY Times

1918 & 2020

April 8, 2020Credit…via Library of Congress, via Associated Press

Why Is This Happening with Chris Hayes

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/msnbc/why-is-this-happening

The Last Great Pandemic with John M. Barry

‘What did we learn from the last great pandemic? You don’t have to dig deep into the 1918 influenza before finding eerie similarities to today – be it the White House downplaying the severity of the virus or the social distancing measures recommended by public health officials. Author John M. Barry’s meticulously researched account of the 1918 pandemic in his book “The Great Influenza” was so affecting that it inspired then President George W. Bush to develop a comprehensive pandemic plan after reading it. There’s no one better to discuss the similarities and differences to what played out a century ago – and the far reaching reverberations this moment will have – than John M. Barry.’

“The failure of the government in this is incomprehensible.

We don’t have a plan.”

-John M. Barry

#MustListen #COVID19US #withpod

NYTimes

The Single Most Important Lesson From the 1918 Influenza

Dark Waters

December 15, 2019See it. #MustSee Excellent.

“The system is rigged. “They want us to think they protect us, but that’s a lie. WE protect us. We do. Nobody else.”

The film is based on the NYTimes article:

“The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare”

Jan. 6, 2016

Rob Bilott on land owned by the Tennants near Parkersburg, W.Va.Credit…Bryan Schutmaat for The New York Times

The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare

Rob Bilott was a corporate defense attorney for eight years. Then he took on an environmental suit that would upend his entire career — and expose a brazen, decades-long history of chemical pollution.

Rob Bilott on land owned by the Tennants near Parkersburg, W.Va.Credit…Bryan Schutmaat for The New York Times

By

‘Just months before Rob Bilott made partner at Taft Stettinius & Hollister, he received a call on his direct line from a cattle farmer. The farmer, Wilbur Tennant of Parkersburg, W.Va., said that his cows were dying left and right. He believed that the DuPont chemical company, which until recently operated a site in Parkersburg that is more than 35 times the size of the Pentagon, was responsible. Tennant had tried to seek help locally, he said, but DuPont just about owned the entire town. He had been spurned not only by Parkersburg’s lawyers but also by its politicians, journalists, doctors and veterinarians. The farmer was angry and spoke in a heavy Appalachian accent. Bilott struggled to make sense of everything he was saying. He might have hung up had Tennant not blurted out the name of Bilott’s grandmother, Alma Holland White.

White had lived in Vienna, a northern suburb of Parkersburg, and as a child, Bilott often visited her in the summers. In 1973 she brought him to the cattle farm belonging to the Tennants’ neighbors, the Grahams, with whom White was friendly. Bilott spent the weekend riding horses, milking cows and watching Secretariat win the Triple Crown on TV. He was 7 years old. The visit to the Grahams’ farm was one of his happiest childhood memories.

When the Grahams heard in 1998 that Wilbur Tennant was looking for legal help, they remembered Bilott, White’s grandson, who had grown up to become an environmental lawyer. They did not understand, however, that Bilott was not the right kind of environmental lawyer. He did not represent plaintiffs or private citizens. Like the other 200 lawyers at Taft, a firm founded in 1885 and tied historically to the family of President William Howard Taft, Bilott worked almost exclusively for large corporate clients. His specialty was defending chemical companies. Several times, Bilott had even worked on cases with DuPont lawyers. Nevertheless, as a favor to his grandmother, he agreed to meet the farmer. ‘‘It just felt like the right thing to do,’’ he says today. ‘‘I felt a connection to those folks.’’’

Credit…Bryan Schutmaat for The New York Times.]

The connection was not obvious at their first meeting. About a week after his phone call, Tennant drove from Parkersburg with his wife to Taft’s headquarters in downtown Cincinnati. They hauled cardboard boxes containing videotapes, photographs and documents into the firm’s glassed-in reception area on the 18th floor, where they sat in gray midcentury-modern couches beneath an oil portrait of one of Taft’s founders. Tennant — burly and nearly six feet tall, wearing jeans, a plaid flannel shirt and a baseball cap — did not resemble a typical Taft client. ‘‘He didn’t show up at our offices looking like a bank vice president,’’ says Thomas Terp, a partner who was Bilott’s supervisor. ‘‘Let’s put it that way.’’

VOX

Dark Waters isn’t your typical Todd Haynes movie. The director of a varied array of movies like Velvet Goldmine, Far From Heaven, and Carol is known for his pioneering queer cinema and lush, haunting tales of love and fear.

A whistleblower drama based on a real-life story — more a work of social realism and protest than anything else — isn’t an obvious fit for his style, then. Yet Dark Waters still works, thanks to a compelling story and performance from Mark Ruffalo. Based on a New York Times article titled “The Lawyer Who Became DuPont’s Worst Nightmare,” the movie tells the story of Rob Bilott, an attorney at a large corporate firm in Cincinnati who discovers that the people in his West Virginia hometown are becoming ill and dying from mysterious causes that seem linked to the DuPont Chemical plant in town.

https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/12/3/20970804/dark-waters-interview-todd-haynes-mark-ruffalo

“I am wise, but it’s wisdom born of pain.”

January 9, 2019[Helen Reddy on the Midnight Special, 1971.]

I Am (an Older) Woman. Hear Me Roar.

Nancy Pelosi, Glenn Close, Susan Zirinsky of CBS: The news has been filled with powerful women over 60.

NYTIMES

When Susan Zirinsky takes over CBS News in March, she will be the first woman to hold the job. She will also be the oldest person to assume the role, at 66.

Her appointment was announced just days after Nancy Pelosi, 78, was re-elected Speaker of the House of Representatives — making her the most powerful elected woman in United States history — and Representative Maxine Waters became the first woman and African-American to lead the Financial Services Committee, at age 80.

News of Ms. Zirinsky’s ascension broke on the same evening that 71-year-old Glenn Close bested four younger women to win the Golden Globe for best actress.

It seems that older women, long invisible or shunted aside, are experiencing an unfamiliar sensation: power.

There are more women over 50 in this country today than at any other point in history, according to data from the United States Census Bureau. Those women are healthier, are working longer and have more income than previous generations.

That is creating modest but real progress in their visibility and stature.

“Age — don’t worry about it. It’s a state of mind,” Ms. Zirinsky said on Tuesday when asked about the effect of her age on her new job. “I have so much energy that my staff did an intervention when I tried a Red Bull.”

[Susan Zirinsky at CBS News on Monday.]

Susan Douglas, a professor of communication studies at the University of Michigan who is writing a book on the power of older women, said “a demographic revolution” was occurring — both in the number of women who are working into their 60s and 70s and in the perception, in the wake of #MeToo, of their expertise and value.

“Older women are now saying ‘No, I’m still vibrant, I still have a lot to offer, and I’m not going to be consigned to invisibility,’ ” she said. “These women are reinventing what it means to be an older woman.”

“Ageism is one of the last acceptable biases in our culture, but it powerfully intersects with sexism,” Professor Douglas said.

But the arc of women’s working lives is changing, as is the broader perception of them. Many older women like to work, demographers say, a reality they first experienced decades ago, when opportunities began to open to them in the 1970s and 1980s.

“What the women’s movement did was develop generations of strong women,” said Representative Donna Shalala, Democrat of Florida, who became the oldest freshman in her House class when she took office a little over a month before her 78th birthday. “We had professional careers, we were achievers in our fields, and you’re seeing the result of that now. And we’re comfortable in our own skin, and we don’t put up with nonsense, and we have a sisterhood.”

[“Age is just a number,” said Representative Donna Shalala of Florida, center, who became the oldest freshman in her House class when she took office a little over a month before her 78th birthday.]

‘Freedom. And community.’

August 24, 2016‘Millennials are oriented around neighborhood hospitality, rather than national identity or the borderless digital world. […] I get the sense a lot of people are actually about to make the break and immerse themselves in demanding local community movements. […] If millennials are heading anywhere, it seems to be in the direction of community.’

Full article:

“In 18th-century America, colonial society and Native American society sat side by side. The former was buddingly commercial; the latter was communal and tribal. As time went by, the settlers from Europe noticed something: No Indians were defecting to join colonial society, but many whites were defecting to live in the Native American one.

This struck them as strange. Colonial society was richer and more advanced. And yet people were voting with their feet the other way.

The colonials occasionally tried to welcome Native American children into their midst, but they couldn’t persuade them to stay. Benjamin Franklin observed the phenomenon in 1753, writing, “When an Indian child has been brought up among us, taught our language and habituated to our customs, yet if he goes to see his relations and make one Indian ramble with them, there is no persuading him ever to return.”

During the wars with the Indians, many European settlers were taken prisoner and held within Indian tribes. After a while, they had plenty of chances to escape and return, and yet they did not. In fact, when they were “rescued,” they fled and hid from their rescuers.

Sometimes the Indians tried to forcibly return the colonials in a prisoner swap, and still the colonials refused to go. In one case, the Shawanese Indians were compelled to tie up some European women in order to ship them back. After they were returned, the women escaped the colonial towns and ran back to the Indians.

Even as late as 1782, the pattern was still going strong. Hector de Crèvecoeur wrote, “Thousands of Europeans are Indians, and we have no examples of even one of those aborigines having from choice become European.”

I first read about this history several months ago in Sebastian Junger’s excellent book “Tribe.” It has haunted me since. It raises the possibility that our culture is built on some fundamental error about what makes people happy and fulfilled.

The native cultures were more communal. As Junger writes, “They would have practiced extremely close and involved child care. And they would have done almost everything in the company of others. They would have almost never been alone.

If colonial culture was relatively atomized, imagine American culture of today. As we’ve gotten richer, we’ve used wealth to buy space: bigger homes, bigger yards, separate bedrooms, private cars, autonomous lifestyles. Each individual choice makes sense, but the overall atomizing trajectory sometimes seems to backfire. According to the World Health Organization, people in wealthy countries suffer depression by as much as eight times the rate as people in poor countries.

There might be a Great Affluence Fallacy going on — we want privacy in individual instances, but often this makes life generally worse.

Every generation faces the challenge of how to reconcile freedom and community — “On the Road” versus “It’s a Wonderful Life.” But I’m not sure any generation has faced it as acutely as millennials.

In the great American tradition, millennials would like to have their cake and eat it, too. A few years ago, Macklemore and Ryan Lewis came out with a song called “Can’t Hold Us,” which contained the couplet: “We came here to live life like nobody was watching/I got my city right behind me, if I fall, they got me.” In the first line they want complete autonomy; in the second, complete community.

But, of course, you can’t really have both in pure form. If millennials are heading anywhere, it seems to be in the direction of community. Politically, millennials have been drawn to the class solidarity of the Bernie Sanders campaign. Hillary Clinton — secretive and a wall-builder — is the quintessence of boomer autonomy. She has trouble with younger voters.

Professionally, millennials are famous for bringing their whole self to work: turning the office into a source of friendships, meaning and social occasions.

I’m meeting more millennials who embrace the mentality expressed in the book “The Abundant Community,” by John McKnight and Peter Block. The authors are notably hostile to consumerism.

They are anti-institutional and anti-systems. “Our institutions can offer only service — not care — for care is the freely given commitment from the heart of one to another,” they write.

Millennials are oriented around neighborhood hospitality, rather than national identity or the borderless digital world. “A neighborhood is the place where you live and sleep.” How many of your physical neighbors know your name?

Maybe we’re on the cusp of some great cracking. Instead of just paying lip service to community while living for autonomy, I get the sense a lot of people are actually about to make the break and immerse themselves in demanding local community movements. It wouldn’t surprise me if the big change in the coming decades were this: an end to the apotheosis of freedom; more people making the modern equivalent of the Native American leap.”

-David Brooks

Bernie supporters at a rally in the Bronx, NY. (NY TIMES)

‘…the task of making amends.’

April 16, 2016NYTimes

—

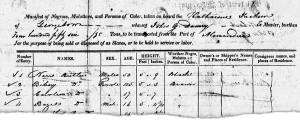

‘272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does It Owe Their Descendants

More than a dozen universities — including Brown, Columbia, Harvard and the University of Virginia — have publicly recognized their ties to slavery and the slave trade. But the 1838 slave sale organized by the Jesuits, who founded and ran Georgetown, stands out for its sheer size, historians say.

At Georgetown, slavery and scholarship were inextricably linked. The college relied on Jesuit plantations in Maryland to help finance its operations, university officials say. (Slaves were often donated by prosperous parishioners.) And the 1838 sale — worth about $3.3 million in today’s dollars — was organized by two of Georgetown’s early presidents, both Jesuit priests.

[…]

“This is not a disembodied group of people, who are nameless and faceless,” said Mr. Cellini, 52, whose company, Briefcase Analytics, is based in Cambridge, Mass. “These are real people with real names and real descendants.”

Within two weeks, Mr. Cellini had set up a nonprofit, the Georgetown Memory Project, hired eight genealogists and raised more than $10,000 from fellow alumni to finance their research.

Dr. Rothman, the Georgetown historian, heard about Mr. Cellini’s efforts and let him know that he and several of his students were also tracing the slaves. Soon, the two men and their teams were working on parallel tracks.

What has emerged from their research, and that of other scholars, is a glimpse of an insular world dominated by priests who required their slaves to attend Mass for the sake of their salvation, but also whipped and sold some of them. The records describe runaways, harsh plantation conditions and the anguish voiced by some Jesuits over their participation in a system of forced servitude.

“A microcosm of the whole history of American slavery,” Dr. Rothman said.

The enslaved were grandmothers and grandfathers, carpenters and blacksmiths, pregnant women and anxious fathers, children and infants, who were fearful, bewildered and despairing as they saw their families and communities ripped apart by the sale of 1838.

The researchers have used archival records to follow their footsteps, from the Jesuit plantations in Maryland, to the docks of New Orleans, to three plantations west and south of Baton Rouge, La.

158.

October 10, 2015The number of families that have contributed to nearly half of early money efforts to capture the Whitehouse. They are ‘white, rich, and older male.’

-NYTimes

NYTimes…

April 13, 2015Cycle of low wages and federal aid…