FOX News

Democracy dies in darkness.

May 1, 2022Finally, a publication digging deep and giving light to the social and cultural cancer that is Rupert Murdoch’s FOX news and specifically to the hate and darkness that is Tucker Carlson. This is the first of three parts, available to all, that is, not blocked by a pay wall.

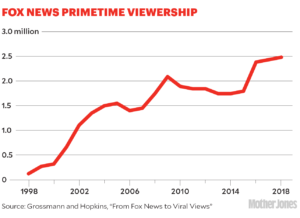

Please read and discover how a man who inherited his father’s broadcast talent only to turn his platform into a vehicle for hate and meanness to weaken, perhaps destroy, the fabric of our democracy, “you vs. them”…distrust of other…night after night, reaching three million views each broadcast, with his poisoned tentacles of disinformation, lies, and clouded deceit reaching across platforms and computers. Ideology? Maybe. More likely because he found a message that gave him the opportunity he wanted, to make money, millions. This is what he always wanted to have, especially after being abandoned by his mother, who “didn’t like him.” He allowed this personal darkness to shape his destiny, and ours. -dayle

How Tucker Carlson Stoked White Fear to Conquer Cable

April 30, 2022

American Nationalist: part 1

Reporting was contributed by Larry Buchanan, Weiyi Cai, Ben Decker, Barbara Harvey, Candice Reed, Michael D. Shear and Karen Yourish. Julie Tate contributed research. Nicholas Confessore is a New York-based political and investigative reporter and a staff writer at the Times Magazine, covering the intersection of wealth, power and influence in Washington and beyond. He joined The Times in 2004.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/30/us/tucker-carlson-fox-news.html?smid=url-share

Often think back to this this post on Twitter from an encounter with Carlson at a fly fishing shop in Montana; it brings hope there are, could be, so many more democratic citizens in this country who feel, who know, the same. -dayle

“You are the worst human being known to man.”

—

“Moneyball” for television: a data-driven, audience-first approach to deciding what to cover and how to cover it.

Lachlan Murdoch — sole heir to the throne. He’s widely viewed as having more conservative politics than his father.’

Trevor Noah at the White House Correspondence Dinner, April 30th, 2022:

“What we’re here for is to honor and celebrate the 4th Estate…and what you stand for…what you stand for…an additional check and balance that holds power to account and gives voice to those who otherwise wouldn’t have one.”

[Pick up his closing remarks at 22:45.]

[Image: CNN]

‘Civil’ Society

October 8, 2021Kurt Thigpen was met with vitriol shortly after he became a school board member in Washoe County, Nevada. Credit: David Calvert, special to ProPublica

We’re Losing Our Humanity, and the Pandemic Is to Blame

“What the hell is happening? I feel like we are living on another planet. I don’t recognize anyone anymore.”

by Sarah Smith

Kurt Thigpen clenched his hands around the edge of the table because if he couldn’t feel the sharp edges digging into his palms, he would have to think about how hard his heart was beating. He was grateful that his mask hid his expression. He hoped that no one could see him sweat.

A woman approached the lectern in the center aisle, a thick American flag scarf looped around her neck.

“Do you realize the mask, the CDC said it’s only 2% effective?” she demanded. “You’re failing our children, you’re failing our country, you’re failing our students’ future ….”

Thigpen fixed his eyes on a spot in the back of the blue-and-green auditorium. He let the person speaking at the lectern fade. It will be over soon, he told himself.

“No, you’re not the boss of me, you work for us, I can’t breathe with it on —”

“Ma’am —”

“Don’t you dare cut my microphone —”

The crowd cheered. Thigpen focused on his breathing.

It will end soon, he told himself. It must. His sweat turned cold under his suit.

“The science isn’t there, take the kids outta the masks and let’s move on.”

When the eight-hour meeting finally ended, he would drive home and pull off the suit and rip off his shirt. He would only take care with his rainbow tie, resting it gently in the closet. It still hangs there today. He would close the door, lay down on his bed, and let himself cry.

The stories of cruel, seemingly irrational and sometimes-violent conflicts over coronavirus regulations have become lingering symptoms of the pandemic as it drags through its second year. Two men on a Mesa-to-Provo flight got into a cross-aisle fight after one refused to wear a mask. A Tennessee teenager asking his school board to impose a mask mandate in honor of his grandmother who died of COVID-19 got jeered by the crowd. A California parent angered by the requirement that his child wear a mask allegedly beat up a teacher so badly that the teacher had to go to the emergency room. An Arizona father showed up to an elementary school with zip ties, allegedly intending to make a “citizen’s arrest” over COVID-19 rules. A Missouri medical center has distributed panic buttons to about 400 employees after an increase in assaults on health care workers by people frustrated over coronavirus-induced visitation restrictions and long wait times.

“What the hell is happening?” said Rachel Patterson, who owns a hair salon in Huntsville, Alabama, and who has been screamed at, cussed out and walked out on for asking clients to don a mask. “Like, I feel like we are living on another planet. Like I don’t — I don’t recognize anyone anymore.”

Full piece: https://www.propublica.org/article/were-losing-our-humanity-and-the-pandemic-is-to-blame

Upworthy:

The National School Boards Association sent a letter to the Biden Administration stating that, “These heinous actions could be the equivalent to a form of domestic terrorism and hate crimes.”

The threats have prompted U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland to address the issue. In response, Garland directed federal authorities to meet with local law enforcement over the next month to discuss strategies for addressing the increase in “harassment, intimidation and threats of violence against school board members, teachers and workers” in public schools across the country.

Just about every American would agree that we should work to protect school board members from threats of violence. However, Fox News reporter Peter Doocy used Garland’s decision to crack down on violent threats as a way to rile up conservatives.

Just about every American would agree that we should work to protect school board members from threats of violence. However, Fox News reporter Peter Doocy used Garland’s decision to crack down on violent threats as a way to rile up conservatives.

He completely mischaracterized Garland’s directive in a question he asked White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki on Wednesday.

“Does the administration agree that parents upset about their kids’ curriculums could be considered domestic terrorists?” he asked.

“Let me unravel this a little bit,” Psaki answered, saying that Garland is “correct” to say that threats of violence against public servants “run counter to our nation’s core values.”

“Regardless of the reasoning,” she said, “threats and violence against public servants is illegal.”

FOX NEWS mandate from TV host Tucker Carlson [HuffPost]

Your response when you see children wearing masks as they play should be no different from your response when you see someone beat a kid in Walmart. Call the police immediately. Contact child protective services. Keep calling until someone arrives. What you’re looking at is abuse, it’s child abuse, and you’re morally obligated to attempt to prevent it.”

MOTHER JONES:

September/October issue

The Real Source of America’s Rising Rage

We are at war with ourselves, but not for the reasons you think.

by Kevin Drum

Americans sure are angry these days. Everyone says so, so it must be true.

But who or what are we angry at? Pandemic stresses aside, I’d bet you’re not especially angry at your family. Or your friends. Or your priest or your plumber or your postal carrier. Or even your boss.

Unless, of course, the conversation turns to politics. That’s when we start shouting at each other. We are way, way angrier about politics than we used to be, something confirmed by both common experience and formal research.

When did this all start? Here are a few data points to consider. From 1994 to 2000, according to the Pew Research Center, only 16 percent of Democrats held a “very unfavorable” view of Republicans, but then these feelings started to climb. Between 2000 and 2014 it rose to 38 percent and by 2021 it was about 52 percent. And the same is true in reverse for Republicans: The share who intensely dislike Democrats went from 17 percent to 43 percent to about 52 percent.

Likewise, in 1958 Gallup asked people if they’d prefer their daughter marry a Democrat or a Republican. Only 28 percent cared one way or the other. But when Lynn Vavreck, a political science professor at UCLA, asked a similar question a few years ago, 55 percent were opposed to the idea of their children marrying outside their party.

Or consider the right track/wrong track poll, every pundit’s favorite. Normallythis hovers around 40–50 percent of the country who think we’re on the right track, with variations depending on how the economy is doing. But shortly after recovering from the 2000 recession, this changed, plunging to 20–30 percent over the next decade and then staying there.

Finally, academic research confirms what these polls tell us. Last year a team of researchers published an international study that estimated what’s called “affective polarization,” or the way we feel about the opposite political party. In 1978, we rated people who belonged to our party 27 points higher than people who belonged to the other party. That stayed roughly the same for the next two decades, but then began to spike in the year 2000. By 2016 it had gone up to 46 points—by far the highest of any of the countries surveyed—and that’s beforeeverything that has enraged us for the last four years.

Journalism Professors Unite

April 4, 2020Every pandemic in history has been followed by a cultural and social blossoming. This one can too, but only if we use this time to reflect on what that blossoming might look like. In the midst of the darkness that’s our slice of light.

~Marianne Williamson

From Journalists and Teachers of Journalism

“Americans consistently rate the Fox News Channel as one of the most trusted TV channels. The average age of Fox News viewers is 65. It is well established that this population incurs the greatest risk from the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, Fox News viewers are at special risk from the coronavirus.

But viewers of Fox News, including the president of the United States, have been regularly subjected to misinformation relayed by the network — false statements downplaying the prevalence of COVID-19 and its harms; misleading recommendations of activities that people should undertake to protect themselves and others, including casual recommendations of untested drugs; false assessments of the value of measures urged upon the public by their elected political leadership and public health authorities.

The misinformation that reaches the Fox News audience is a danger to public health. Indeed, it is not an overstatement to say that your misreporting endangers your own viewers — and not only them, for in a pandemic, individual behavior affects significant numbers of other people as well.

Yet by commission as well as omission — direct, uncontested misinformation as well as failure to report the true dimensions of the crisis — Fox News has been derelict in its duty to provide clear and accurate information about COVID-19. As the virus spread across the world, Fox News hosts and guests minimized the dangers, accusing Democrats and the media of inflating the dangers (in Sean Hannity’s words) to “bludgeon Trump with this new hoax.” Such commentary encouraged President Trump to trivialize the threat and helped obstruct national, state, and local efforts to limit the coronavirus.

The network’s delinquency was effective. According to a YouGov/Economist poll conducted March 15–17, Americans who pay the most attention to Fox News are much less likely than others to say they are worried about the coronavirus. A Pew Research poll found that 79% of Fox News viewers surveyed believed the media had exaggerated the risks of the virus. 63% of Fox viewers said they believed the virus posed a minor threat to the health of the country. As recently as Sunday, March 22, Fox News host Steve Hilton deplored accurate views of the pandemic, which he attributed to “our ruling class and their TV mouthpieces — whipping up fear over this virus.”

Fox News reporters have done some solid reporting. And the network has recently given some screen time to medical and public health professionals. But Fox News does not clearly distinguish between the authority that should accrue to trained experts, on the one hand, and the authority viewers grant to pundits and politicians for reasons of ideological loyalty. There is a tendency to accept (or reject) them all indiscriminately, for after all, they are talking heads who appear on Fox News, a trusted source of news. When the statements of knowledgeable experts are surrounded by false claims made by pundits and politicians, including President Trump — claims that are not rebutted by knowledgeable people in real time — the overall effect is to mislead a vulnerable public about risks and harms. Misinformation furthers the reach and the dangers of the pandemic. For example, the day after Tucker Carlson touted a flimsy French study on the use of two drugs to treat COVID-19, President Trump touted “very, very encouraging early results” from those drugs, and promoted a third as a possible “game changer.”

The basic purpose of news organizations is to discover and tell the truth. This is especially necessary, and obvious, amid a public health crisis. Television bears a particular responsibility because even more millions than usual look there for reliable information.

Inexcusably, Fox News has violated elementary canons of journalism. In so doing, it has contributed to the spread of a grave pandemic. Urgently, therefore, in the name of both good journalism and public health, we call upon you to help protect the lives of all Americans — including your elderly viewers — by ensuring that the information you deliver is based on scientific facts.”

Signed*,

(If you are a journalist or teacher of journalism and would like to add your name, click here.)

Todd Gitlin, Professor, Chair, Ph. D. Program in Communications, Columbia Journalism School

Mark Feldstein, Eaton Chair of Broadcast Journalism, University of Maryland

Frances FitzGerald, Pulitzer Prize-winning author

Adam Hochschild, Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley

Edward Wasserman, Dean, Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley

Lisa R. Cohen; Columbia Journalism School

Gerald Johnson, Texas Student Media

Susan Moeller, Professor, Merrill College of Journalism, UMD, College Park

Maurine Beasley, University of Maryland College Park

Michael Deas, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University

Ivan Meyers, Medill School at Northwestern University

Helen Benedict, Professor, Graduate School of Journalism, Columbia University

Hendrik Hertzberg, longtime staff writer and editor, The New Yorker

Lewis Friedland, Vilas Distinguished Achievement Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Com, UW-Madison

Dr. Tom Mascaro, Ph.D. Bowling Green State University, School of Media & Communication

Tom Bettag, Visiting Fellow, University of Maryland

Betty H Winfield University of Missouri Curators’ Professor Emerita

Frank D. Durham, University of Iowa

Dennis Darling Professor, School of Journalism, The University of Texas at Austin

Jonathan Weiner, Maxwell M. Geffen Professor of Medical and Scientific Journalism Columbia Journalism School

Ari L. Goldman, professor, Columba University Graduate School of Journalism

Jennifer Kahn, Narrative Program Lead, Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley

Meenakshi Gigi Durham, Professor, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Iowa

Deirdre English, Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley

Rosental C Alves, University of Texas at Austin

Pauline Dakin, Ass. Professor, University of King’s College, Halifax, Nova Scotia

Nina Alvarez, Assistant Professor, Columbia Journalism School

Travis Vogan, University of Iowa

Ali Noor Mohamed, United Arab Emirates University

Linda Steiner, Acting Director, Ph.D. Studies; Professor, Phillip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland, College Park

Lucas Graves, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, UW — Madison

Anna Everett, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Santa Barbara

Richard Appelbaum, Fielding Graduate University; UCSB Emeritus

Tom Collinger, Northwestern University, Medill School of Journalism

Wenhong Chen, Founding Co-director, Center for Entertainment and Media Industries Associate Professor ofMedia Studies and Sociology, Moody College of Communication The University of Texas at Austin

LynNell Hancock, Professor, Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

Donna DeCesare, Associate Professor, School of Journalism, University of Texas at Austin

Barbie Zelizer, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania

Michael Murray, UM Curators Distinguished Professor Emeritus, UM-St. Louis

Michael Schudson, Columbia University

Martin Kaplan, Norman Lear Chair in Entertainment, Media and Society, USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Brian Ekdale, University of Iowa

Gina Masullo, University of Texas at Austin

Krishnan Vasudevan, Assistant Professor, Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland at College Park

Harold Evans, former editor Sunday Times and The Times, London

Chuck Howell, Librarian for Journalism & Communication Studies, University of Maryland

Clarke L. Caywood Ph.D, Professor Medill School of Journalism Media Integrated Marketing Communications

Andie Tucher, Director, PhD program in Communications, Columbia Journalism School

Kalyani Chadha, Associate Professor, University of Maryland

Denis P. Gorman, Freelance Journalist

Jon Marshall, Northwestern University

Kevin Lerner, Marist College

Joel Whitebook, Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research

Abe Peck, Prof. Emeritus in Service, Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications, Northwestern University

Carrie Lozano, Graduate School of Journalism, UC Berkeley

Susie Linfield, Dept of Journalism, New York University

Charles Berret, University of British Columbia

Jay Rosen, Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, New York University

Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, Professor of Journalism, The University of Texas at Austin

Joseph Straubhaar, Professor, School of Journalism, University of Texas, Austin

Edward C Malthouse, Haven Professor, Medill School of Journalism, Media and IMC, Northwestern University

Mitchell Stephens, Professor of Journalism, New York University

Patricia Loew, Ph.D. Professor, Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University

Richard Fine, Professor of English, Virginia Commonwealth University

John E. Newhagen Associate Prof. Emeritus University of Marylans

Caryn Ward, Northwestern University, Medill School of Journalism, Media and Integrated Marketing and Communication

David Hajdu, Professor, Columbia Graduate School of Journalism

Naeemul Hassan, Assistant Professor, University of Maryland

Stephen D. Reese, School of Journalism & Media, U of Texas at Austin

Kevin Klose, Professor, University of Maryland

John Vivian, Winona State University

Sue Robinson, Helen Firstbrook Franklin Professor of Journalism, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Thomas P. Oates, University of Iowa

Samuel Freedman, Columbia Journalism School

Susan Mango Curtis, Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University

Prof. Robert S. Boynton, Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at NYU

Leonard Steinhorn, Professor of Communication and Affiliate Professor of History, American University

J.A. Adande, Medill School, Northwestern

Victor Pickard, University of Pennsylvania

Summer Harlow, Assistant Professor, University of Houston

Danielle K. Kilgo, Ph.D., Indiana University

Jack Doppelt, Northwestern University

Gerry Lanosga, The Media School, Indiana University

Martin Riedl, PhD Candidate, School of Journalism, The University of Texas at Austin

Rich Shumate, School of Media, Western Kentucky University

Mac McKerral, School of Media, Western Kentucky University

Mel Coffee, University of Maryland

David J. Vergobbi, University of Utah

Tom Boll, part-time instructor, S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University

Dannagal G. Young, Associate Professor of Communication and Political Science, University of Delaware

Ken Light, Reva and David Logan Professor of Photojournalism, UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism

George Harmon, emeritus faculty, Medill School of Journalism

Rachel Young, University of Iowa

Carol M. Liebler, Professor, Newhouse School, Syracuse University

Kyu Ho Youm, University of Oregon

Julianne H Newton, University of Oregon

Bethany Swain, University of Maryland

Gi Woong Yun, Reynolds School of Journalism, University of Nevada, Reno

Thomas E. Winski, MJE Retired Assistant Professor of Journalism, Emporia State University

Roy L Moore, Professor (retired), Middle TN State University

Ira Chinoy, Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland

Jay Edwin Gillette, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Information and Communication Sciences Center for Information and Communication Sciences, Ball State University

Michael Anderson, retired journalist

Kimberley Shoaf, Professor of Public Health, University of Utah

Erica Ciszek, University of Texas at Austin

Daniel C. Hallin, University of California, San Diego

Keith W. Strandberg, Webster University, Geneva

Sophie Furley, Editor

Frank Sesno, Director, George Washington University School of Media and Public Affairs

Timothy V. Klein, Louisiana State University

*Affiliations listed for identification only.

https://medium.com/@journalismprofs/open-letter-to-the-murdochs-9334e775a992

Cancel Everything

March 11, 2020The Atlantic

Social distancing is the only way to stop the coronavirus. We must start immediately.

The first fact is that, at least in the initial stages, documented cases of COVID-19 seem to increase in exponential fashion. On the 23rd of January, China’s Hubei province, which contains the city of Wuhan, had 444 confirmed COVID-19 cases. A week later, by the 30th of January, it had 4,903 cases. Another week later, by the 6th of February, it had 22,112.

The same story is now playing out in other countries around the world. Italy had 62 identified cases of COVID-19 on the 22nd of February. It had 888 cases by the 29th of February, and 4,636 by the 6th of March.

Because the United States has been extremely sluggish in testing patients for the coronavirus, the official tally of 604 likely represents a fraction of the real caseload. But even if we take this number at face value, it suggests that we should prepare to have up to 10 times as many cases a week from today, and up to 100 times as many cases two weeks from today.

The second fact is that this disease is deadlier than the flu, to which the honestly ill-informed and the wantonly irresponsible insist on comparing it. Early guesstimates, made before data were widely available, suggested that the fatality rate for the coronavirus might wind up being about 1 percent. If that guess proves true, the coronavirus is 10 times as deadly as the flu.

But there is reason to fear that the fatality rate could be much higher. According to the World Health Organization, the current case fatality rate—a common measure of what portion of confirmed patients die from a particular disease—stands at 3.4 percent. This figure could be an overstatement, because mild cases of the disease are less likely to be diagnosed. Or it could be an understatement, because many patients have already been diagnosed with the virus but have not yet recovered (and may still die).

When the coronavirus first spread to South Korea, many observers pointed to the comparatively low death rates in the country to justify undue optimism. In countries with highly developed medical systems, they claimed, a smaller portion of patients would die. But while more than half of all diagnosed patients in China have now been cured, most South Korean patients are still in the throes of the disease. Of the 7,478 confirmed cases, only 118 have recovered; the low death rate may yet rise.

Meanwhile, the news from Italy, another country with a highly developed medical system, has so far been shockingly bad. In the affluent region of Lombardy, for example, there have been 7,375 confirmed cases of the virus as of Sunday. Of these patients, 622 had recovered, 366 had died, and the majority were still sick. Even under the highly implausible assumption that all of the still-sick make a full recovery, this would suggest a case fatality rate of 5 percent—significantly higher, not lower, than in China.

The third fact is that so far only one measure has been effective against the coronavirus: extreme social distancing.

Before China canceled all public gatherings, asked most citizens to self-quarantine, and sealed off the most heavily affected region, the virus was spreading in exponential fashion. Once the government imposed social distancing, the number of new cases leveled off; now, at least according to official statistics, every day brings more news of existing patients who are healed than of patients who are newly infected.

A few other countries have taken energetic steps to increase social distancing before the epidemic reached devastating proportions. In Singapore, for example, the government quickly canceled public events and installed medical stations to measure the body temperature of passersby while private companies handed out free hand sanitizer. As a result, the number of cases has grown much more slowly than in nearby countries.

These three facts imply a simple conclusion. The coronavirus could spread with frightening rapidity, overburdening our health-care system and claiming lives, until we adopt serious forms of social distancing.

This suggests that anyone in a position of power or authority, instead of downplaying the dangers of the coronavirus, should ask people to stay away from public places, cancel big gatherings, and restrict most forms of nonessential travel.

Given that most forms of social distancing will be useless if sick people cannot get treated—or afford to stay away from work when they are sick—the federal government should also take some additional steps to improve public health. It should take on the costs of medical treatment for the coronavirus, grant paid sick leave to stricken workers, promise not to deport undocumented immigrants who seek medical help, and invest in a rapid expansion of ICU facilities.

The past days suggest that this administration is unlikely to do these things well or quickly (although the administration signaled on Monday that it will seek relief for hourly workers, among other measures). Hence, the responsibility for social distancing now falls on decision makers at every level of society.

Do you head a sports team? Play your games in front of an empty stadium.

Are you organizing a conference? Postpone it until the fall.

Do you run a business? Tell your employees to work from home.

Are you the principal of a school or the president of a university? Move classes online before your students get sick and infect their frail relatives.

Are you running a presidential campaign? Cancel all rallies right now.

All of these decisions have real costs. Shutting down public schools in New York City, for example, would deprive tens of thousands of kids of urgently needed school meals. But the job of institutions and authorities is to mitigate those costs as much as humanly possible, not to use them as an excuse to put the public at risk of a deadly communicable disease.

Finally, the most important responsibility falls on each of us. It’s hard to change our own behavior while the administration and the leaders of other important institutions send the social cue that we should go on as normal. But we must change our behavior anyway. If you feel even a little sick, for the love of your neighbor and everyone’s grandpa, do not go to work.

When the influenza epidemic of 1918 infected a quarter of the U.S. population, killing tens of millions of people, seemingly small choices made the difference between life and death.

As the disease was spreading, Wilmer Krusen, Philadelphia’s health commissioner, allowed a huge parade to take place on September 28; some 200,000 people marched. In the following days and weeks, the bodies piled up in the city’s morgues. By the end of the season, 12,000 residents had died.

In St. Louis, a public-health commissioner named Max Starkloff decided to shut the city down. Ignoring the objections of influential businessmen, he closed the city’s schools, bars, cinemas, and sporting events. Thanks to his bold and unpopular actions, the per capita fatality rate in St. Louis was half that of Philadelphia. (In total, roughly 1,700 people died from influenza in St Louis.)

In the coming days, thousands of people across the country will face the choice between becoming a Wilmer Krusen or a Max Starkloff.

In the moment, it will seem easier to follow Krusen’s example. For a few days, while none of your peers are taking the same steps, moving classes online or canceling campaign events will seem profoundly odd. People are going to get angry. You will be ridiculed as an extremist or an alarmist. But it is still the right thing to do.

Rupert Murdoch could save lives by forcing Fox News to tell the truth about coronavirus — right now

By

There’s one person who could transform all that in an instant: Fox founder Rupert Murdoch, the Australian-born media mogul who, at 89, still exerts his influence on the leading cable network — and thus on the president himself.

Chris Wallace, the independent and tough-minded Fox News interviewer who serves as the network’s chief reality officer, has revealed that the executive chairman of News Corp and co-chairman of Fox Corporation likes to give feedback on what he sees on the network.

“He cares tremendously about the news,” Wallace said, according to the Guardian. “When I have contact with him, he never is asking about ideology, just: ‘What’s going on? What’s happening? Tell me.’ ”

That’s a little hard to believe, given the network’s long history of Clinton-bashing and birtherism lies about Barack Obama, and its peddling of conspiracy theories. But Murdoch’s ultimate power at the network is not in question.

So imagine if the word flowed down from on high that Fox News should communicate to Trump that he needs to take an entirely new tack on the virus. Imagine if Murdoch ordered the network to end its habit of praising him as if he were the Dear Leader of an authoritarian regime and to instead use its influence to drive home the seriousness of the moment.

Would it matter? No doubt.

The network’s influence on Trump is clear from the presidential tweets that follow fast on the heels of a Fox News broadcast. He was always a fan of Fox News, but after entering the White House, he made it even more of an obsessive daily habit, Bloomberg News reported in 2017, to the extent of blotting out dissenting voices from other sources.

Trump made specific reference to his reliance on Fox News during his misleading press event Friday, when he offered unwarranted reassurance rather than urging extreme caution and decisive action: “As of the time I left the plane . . . we had 240 cases — that’s at least what was on a very fine network known as Fox News.”

The message: Go about your business, America, and it will all disappear soon.

Days later, 30 deaths and more than 1,000 cases have been reported in the United States, with those numbers expected to grow exponentially. (By contrast, German Chancellor Angela Merkel is telling hard truths: As much as 70 percent of that country could end up being infected.)

Matt Gertz, a Media Matters senior fellow and the foremost chronicler of the insidious Trump-Fox News feedback loop, connected the dots: “Roughly an hour before his comments, a Fox News medical correspondent argued on-air that coronavirus was no more dangerous than the flu; a few hours later, the same correspondent argued that coronavirus fears were being deliberately overblown in hopes of damaging Trump politically.”

He added: “The network’s personalities have frequently claimed that the Trump administration has been doing a great job responding to coronavirus, that the fears of the disease are overblown, and that the real problem is Democrats and the media politicizing the epidemic to prevent Trump’s reelection.”

On Fox Business Channel, host Trish Regan drew widespread condemnation for her over-the-top rant in Trump’s defense: “The chorus of hate being leveled at the president is nearing a crescendo as Democrats blame him and only him for a virus that originated halfway around the world. This is yet another attempt to impeach the president.”

(By contrast, her Fox News colleague Tucker Carlson has taken the threat seriously, though using it as an excuse to stoke anti-China sentiment along the way.)

But it’s not just the opinionators such as Regan and Trump whisperer Sean Hannity who are at fault. The news segments — while certainly more tied to reality — seldom push back in a meaningful way against the Trump message.

On Tuesday, news anchors Bret Baier and Martha MacCallum docilely sat back and lobbed soft questions while the president’s son Eric praised his father’s crisis-management skills and blamed liberal media figures who criticize him: “He could cure cancer tomorrow and they’d say it wasn’t fast enough.”

Even if all that changed today, great harm has already been done. As The Washington Post and others have documented, the administration has repeatedly squandered chances to prepare for and manage the global epidemic.

But every moment still counts. Lives can be saved by prudent practices and aggressive government action — and lost by their absence.

But it takes leadership from the top. And so, let’s acknowledge the obvious: There is no more important player in influencing Trump than Fox News. And no more powerful figure at Fox than its patriarch.

Murdoch might consider, too, that with the median age of Fox’s viewers around 65, they are among the most vulnerable to the virus’s threats.

For Fox News, a late-breaking change of heart might finally combine a wise business decision with what’s good for the world.

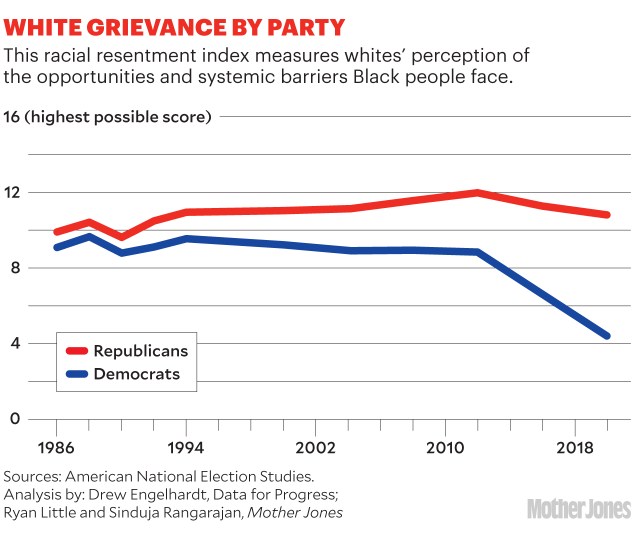

What do we know about more recent views of racism? One thing we know for sure is that both white and Black Americans have gotten

What do we know about more recent views of racism? One thing we know for sure is that both white and Black Americans have gotten