‘Don’t ask whether you need an umbrella. Go outside and stop the rain.’

“It’s not too late,” Jimmy Stewart pleaded with Congress, rasping, exhausted, in “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” in 1939. “Great principles don’t get lost once they come to light.” It wasn’t too late. It’s still not too late.

New Dealers were trying to save the economy; they ended up saving democracy. They built a new America; they told a new American story. On New Deal projects, people from different parts of the country labored side by side, constructing roads and bridges and dams, everything from the Lincoln Tunnel to the Hoover Dam, joining together in a common endeavor, shoulder to the wheel, hand to the forge. Many of those public-works projects, like better transportation and better electrification, also brought far-flung communities, down to the littlest town or the remotest farm, into a national culture, one enriched with new funds for the arts, theatre, music, and storytelling. With radio, more than with any other technology of communication, before or since, Americans gained a sense of their shared suffering, and shared ideals: they listened to one another’s voices.

This didn’t happen by accident. Writers and actors and directors and broadcasters made it happen. They dedicated themselves to using the medium to bring people together. Beginning in 1938, for instance, F.D.R.’s Works Progress Administration produced a twenty-six-week radio-drama series for CBS called “Americans All, Immigrants All,” written by Gilbert Seldes, the former editor of The Dial. “What brought people to this country from the four corners of the earth?” a pamphlet distributed to schoolteachers explaining the series asked. “What gifts did they bear? What were their problems? What problems remain unsolved?” The finale celebrated the American experiment: “The story of magnificent adventure! The record of an unparalleled event in the history of mankind!”

The year 1935 happened to mark the centennial of the publication of Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” an occasion that elicited still more lectures from European intellectuals coming to the United States to remark on its system of government and the character of its people, close on Tocqueville’s heels.

The endless train of academics were also called upon to contribute to the nation’s growing number of periodicals. In 1937, The New Republic, arguing that “at no time since the rise of political democracy have its tenets been so seriously challenged as they are today,” ran a series on “The Future of Democracy,” featuring pieces by the likes of Bertrand Russell and John Dewey. “Do you think that political democracy is now on the wane?” the editors asked each writer. The series’ lead contributor, the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce, took issue with the question, as philosophers, thankfully, do. “I call this kind of question ‘meteorological,’ ” he grumbled. “It is like asking, ‘Do you think that it is going to rain today? Had I better take my umbrella?’ ” The trouble, Croce explained, is that political problems are not external forces beyond our control; they are forces within our control. “We need solely to make up our own minds and to act.”

Don’t ask whether you need an umbrella. Go outside and stop the rain.

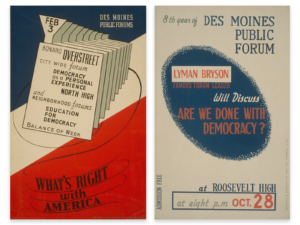

Here are some of the sorts of people who went out and stopped the rain in the nineteen-thirties: schoolteachers, city councillors, librarians, poets, union organizers, artists, precinct workers, soldiers, civil-rights activists, and investigative reporters. They knew what they were prepared to defend and they defended it, even though they also knew that they risked attack from both the left and the right. Charles Beard (Mary Ritter’s husband) spoke out against the newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, the Rupert Murdoch of his day, when he smeared scholars and teachers as Communists. “The people who are doing the most damage to American democracy are men like Charles A. Beard,” said a historian at Trinity College in Hartford, speaking at a high school on the subject of “Democracy and the Future,” and warning against reading Beard’s books—at a time when Nazis in Germany and Austria were burning “un-German” books in public squares. That did not exactly happen here, but in the nineteen-thirties four of five American superintendents of schools recommended assigning only those U.S. history textbooks which “omit any facts likely to arouse in the minds of the students question or doubt concerning the justice of our social order and government.”

The federal government stopped funding the forum program in 1941. Americans would take up their debate about the future of democracy, in a different form, only after the defeat of the Axis. For now, there was a war to fight. And there were still essays to publish, if not about the future, then about the present. In 1943, E. B. White got a letter in the mail, from the Writers’ War Board, asking him to write a statement about “The Meaning of Democracy.” He was a little weary of these pieces, but he knew how much they mattered. He wrote back, “Democracy is a request from a War Board, in the middle of a morning in the middle of a war, wanting to know what democracy is.” It meant something once. And, the thing is, it still does. ♦

[full article]

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/03/the-last-time-democracy-almost-died?

Leave a Reply