Jill Lapore

‘Don’t ask whether you need an umbrella. Go outside and stop the rain.’

January 27, 2020“It’s not too late,” Jimmy Stewart pleaded with Congress, rasping, exhausted, in “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” in 1939. “Great principles don’t get lost once they come to light.” It wasn’t too late. It’s still not too late.

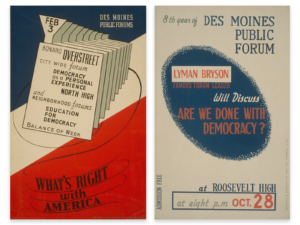

New Dealers were trying to save the economy; they ended up saving democracy. They built a new America; they told a new American story. On New Deal projects, people from different parts of the country labored side by side, constructing roads and bridges and dams, everything from the Lincoln Tunnel to the Hoover Dam, joining together in a common endeavor, shoulder to the wheel, hand to the forge. Many of those public-works projects, like better transportation and better electrification, also brought far-flung communities, down to the littlest town or the remotest farm, into a national culture, one enriched with new funds for the arts, theatre, music, and storytelling. With radio, more than with any other technology of communication, before or since, Americans gained a sense of their shared suffering, and shared ideals: they listened to one another’s voices.

This didn’t happen by accident. Writers and actors and directors and broadcasters made it happen. They dedicated themselves to using the medium to bring people together. Beginning in 1938, for instance, F.D.R.’s Works Progress Administration produced a twenty-six-week radio-drama series for CBS called “Americans All, Immigrants All,” written by Gilbert Seldes, the former editor of The Dial. “What brought people to this country from the four corners of the earth?” a pamphlet distributed to schoolteachers explaining the series asked. “What gifts did they bear? What were their problems? What problems remain unsolved?” The finale celebrated the American experiment: “The story of magnificent adventure! The record of an unparalleled event in the history of mankind!”

The year 1935 happened to mark the centennial of the publication of Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” an occasion that elicited still more lectures from European intellectuals coming to the United States to remark on its system of government and the character of its people, close on Tocqueville’s heels.

The endless train of academics were also called upon to contribute to the nation’s growing number of periodicals. In 1937, The New Republic, arguing that “at no time since the rise of political democracy have its tenets been so seriously challenged as they are today,” ran a series on “The Future of Democracy,” featuring pieces by the likes of Bertrand Russell and John Dewey. “Do you think that political democracy is now on the wane?” the editors asked each writer. The series’ lead contributor, the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce, took issue with the question, as philosophers, thankfully, do. “I call this kind of question ‘meteorological,’ ” he grumbled. “It is like asking, ‘Do you think that it is going to rain today? Had I better take my umbrella?’ ” The trouble, Croce explained, is that political problems are not external forces beyond our control; they are forces within our control. “We need solely to make up our own minds and to act.”

Don’t ask whether you need an umbrella. Go outside and stop the rain.

Here are some of the sorts of people who went out and stopped the rain in the nineteen-thirties: schoolteachers, city councillors, librarians, poets, union organizers, artists, precinct workers, soldiers, civil-rights activists, and investigative reporters. They knew what they were prepared to defend and they defended it, even though they also knew that they risked attack from both the left and the right. Charles Beard (Mary Ritter’s husband) spoke out against the newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, the Rupert Murdoch of his day, when he smeared scholars and teachers as Communists. “The people who are doing the most damage to American democracy are men like Charles A. Beard,” said a historian at Trinity College in Hartford, speaking at a high school on the subject of “Democracy and the Future,” and warning against reading Beard’s books—at a time when Nazis in Germany and Austria were burning “un-German” books in public squares. That did not exactly happen here, but in the nineteen-thirties four of five American superintendents of schools recommended assigning only those U.S. history textbooks which “omit any facts likely to arouse in the minds of the students question or doubt concerning the justice of our social order and government.”

The federal government stopped funding the forum program in 1941. Americans would take up their debate about the future of democracy, in a different form, only after the defeat of the Axis. For now, there was a war to fight. And there were still essays to publish, if not about the future, then about the present. In 1943, E. B. White got a letter in the mail, from the Writers’ War Board, asking him to write a statement about “The Meaning of Democracy.” He was a little weary of these pieces, but he knew how much they mattered. He wrote back, “Democracy is a request from a War Board, in the middle of a morning in the middle of a war, wanting to know what democracy is.” It meant something once. And, the thing is, it still does. ♦

[full article]

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/03/the-last-time-democracy-almost-died?

Needed: Informed Thinkers

January 22, 2019[updated 1.23.19]

“Another brutal day for journalism.”

[Poynter]

by, Tom Jones

“Gannett began slashing jobs all across the country Wednesday in a cost-cutting move that was anticipated even before the recent news that a hedge-fund company was planning to buy the chain.”

~

A Hedge Fund Known for ‘Milking’ Newspapers

Takes Aim at Gannett

By~

Does Journalism Have a Future?

In an era of social media and fake news, journalists who have survived the print plunge have new foes to face.

The New Yorker

Between 1970 and 2016, the year the American Society of News Editors quit counting, five hundred or so dailies went out of business; the rest cut news coverage, or shrank the paper’s size, or stopped producing a print edition, or did all of that, and it still wasn’t enough.

Between January, 2017, and April, 2018, a third of the nation’s largest newspapers, including the Denver Post and the San Jose Mercury News, reported layoffs.

Media companies that want to get bigger tend to swallow up other media companies, suppressing competition and taking on debt, which makes publishers cowards. In 1986, the publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle bought the Worcester Telegram and the Evening Gazette, and, three years later, right about when Time and Warner became Time Warner, the Telegram and the Gazette became

“We are, for the first time in modern history, facing the prospect of how societies would exist without reliable news,” Alan Rusbridger, for twenty years the editor-in-chief of the Guardian, writes in “Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now.”

The big book that inspired Jill Abramson to become a journalist was David Halberstam’s “The Powers That Be,” from 1979, a history of the rise of the modern, corporate-based media in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Halberstam, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting from Vietnam for the New York Times, took up his story more or less where Villard left off. He began with F.D.R. and CBS radio; added the Los Angeles Times, Time Inc., and CBS television; and reached his story’s climax with the Washington Post and the New York Times and the publication of the Pentagon Papers, in 1971.

In 1969, Nixon’s Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, delivered a speech drafted by the Nixon aide Pat Buchanan accusing the press of liberal bias. It’s “good politics for us to kick the press around,” Nixon is said to have told his staff. The press, Agnew said, represents “a concentration of power over American public opinion unknown in history,” consisting of men who “read the same newspapers” and “talk constantly to one another.”

The present crisis, which is nothing less than a derangement of American life, has caused many people in journalism to make decisions they regret, or might yet. In the age of Facebook, Chartbeat, and DT, legacy news organizations, hardly less than startups, have violated or changed their editorial standards in ways that have contributed to political chaos and epistemological mayhem. Do editors sit in a room on Monday morning, twirl the globe, and decide what stories are most important? Or do they watch DT’s Twitter feed and let him decide? It often feels like the latter. Sometimes what doesn’t kill you doesn’t make you stronger; it makes everyone sick. The more adversarial the press, the more loyal DT’s followers, the more broken American public life. The more desperately the press chases readers, the more our press resembles our politics.

This book by Robert W. McChesney and John Nichols (2011) is an important read as pretext to Lapore’s piece.

“Journalism cannot lose 30 percent of its reporting and editing capacity and continue to provide the information needed to maintain a realistic democratic discourse, open government and outlines of civil society at the federal, state and local levels.”

The United States is not experiencing a brief recession for journalism as the silliest commentator continue to suggest; newsrooms will not be repopulated, let along restored to their previous vigor, with an economic recovery. Instead it is an existential crisis, one decades in the making and as we argue heron, it goes directly to the issue of whether this nation can remain a democratic state with liberties and freedoms many take for granted.

The crisis is right here, right now and unless there is forceful policy intervention, an unacceptable circumstance will grow dramatically worse.

In our view the evidence is overwhelming: If Americans are serious about reversing course and dramatically explained and improving journalism, the only way this can happen is with massive public subsidies.

The market is not getting it done, and there is no reason to think it is going to get it done. It will require a huge expansion of the nonprofit news media sector as well. It is imperative to discontinue the practice of regarding journalism as a “business” and evaluating it with business criteria. Instead, embracing the public good nature of journalism is necessary. That is the argument we make in this book.

If the U.S. government subsidized journalism today at the same level of GDP that it did in the 1840’s, the government would have to spend in the neighborhood of $30-35 billion annually. Subsidies are as American as maple pie; indeed, our democratic culture was built on them.

We met with a group of exceptional journalism students wo had read the book and wanted to talk about our proposals. They especially liked our proposal for a ‘Journalism for America’ initiative that would provide young people with stipends to cover underserved communities in the United States. By the end of the dinner they had framed out a plan for linking the ‘Journalism for America’ initiative to the Peace Corps so that young journalists could cover an immigrant community in the United States for a year and then travel wit the Peace Corps to foreign lands with connections to the American communities.

We came away with confidence that, when this great debate opens up, as it has begun to do, American journalism and American democracy will flourish.”

Ed Madison and Ben DeJarnette (2018) write,

“Fundamentally, journalists and teachers have similar roles within a society. They exist to educate us so we can collectively move our communities forward. Yet crises within K-12 education haunt our society’s future prospects: if we’re not raising generations of young people who are thoughtful and informed participants in our democratic process, then the future of journalism–and democracy–is very dark indeed.

The objective is not to spawn future journalists; the intent is to support students with becoming what we refer to as informed thinkers. Educators often speak about cultivating critical thinking, yet the term remains as elusive concept that does not fully encompass the levels of student engagement that young people need to navigate effectively in this increasingly complex and nuanced world.

Informed thinking articulates a clearer method and result than does critical thinking. Students learn to distinguish fact from fiction and to detect biases and agendas.

Our need to improve education is not optional; it is an obligation we must embrace.”

Wonderful book for reference and U.S. history, by Jill Lapore.

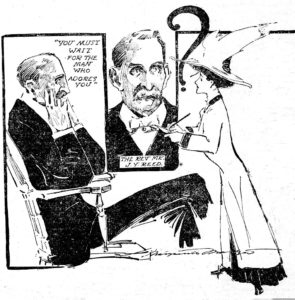

Journalist Marguerite Martyn of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch made this sketch of herself interviewing a Methodist minister in 1908 for his views on marriage.

Ezra Klein

January 7, 2019Too few named journalists have a thorough and deep knowledge of American history, even brilliant contemporary journalists, like Ezra Klein, which he acknowledges in this important podcast with Jill Lapore.

Jill Lapore’s new book, These Truths, A History of the United States [2018], is a one volume tomb far more complex and contemporarily contextualized study of American History than Howard Zinn’s well-known and beloved A People’s History of the United States [1980]. Recommending this book and podcast.

From Ezra:

Jill Lepore is a Harvard historian, a New Yorker contributor, and the author of These Truths, a dazzling one-volume synthesis of American history. She’s the kind of history teacher everyone wishes they’d had, able to effortlessly connect the events and themes of American history to make sense of our past and clarify our present.

“The American Revolution did not begin in 1775 and it didn’t end when the war was over,” Lepore writes. This is a conversation about those revolutions. But more than that, it’s a conversation about who we are as a country, and how that self-definition is always contested and constantly in flux.

And beyond all that, Lepore is just damn fun to talk to. Every answer she gives has something worth chewing over for weeks. You’ll enjoy this one.

Recommended books:

Fear Itself by Ira Katznelson

A Godly Hero by Michael Kazin

The Warmth of Other Sons by Isabel Wilkerson