New York Lands in Boise

“Dawn Whitson, a shelter resident making $12 an hour as a hotel receptionist, said she wanted to know why the city was spending potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight the suit instead of putting the money toward more shelter beds or homeless services.”

NYTimes

How Far Can Cities Go to Police the Homeless? Boise Tests the Limit

A decade-old legal fight shapes a mayoral race and offers the Supreme Court a chance to weigh in.

BOISE, Idaho — During a recent mayoral debate at a Boise homeless shelter, after disposing of icebreakers like the candidates’ favorite Metallica album, the moderator turned to something more contentious: a decade-old lawsuit, now a step away from the Supreme Court. The case, Boise v. Martin, is examining whether it’s a crime for someone to sleep outside when they have nowhere else to go.

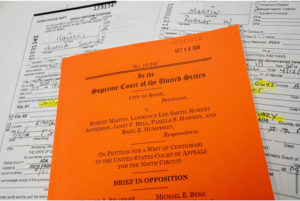

The suit arose when a half-dozen homeless people claimed that local rules prohibiting camping on public property violated the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment. The plaintiffs prevailed at the appellate level last year, putting the city at the center of a national debate on how to tackle homelessness. Now Boise — after hiring a powerhouse legal team that includes Theodore B. Olson and Theane Evangelis of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher — has asked the Supreme Court to take the case, a decision that could come within days.

Nobody at Interfaith Sanctuary, a shelter for 164 with bunk beds in neat rows, needed a primer. They had been talking about it for weeks. Before the debate, Dawn Whitson, a shelter resident making $12 an hour as a hotel receptionist, said she wanted to know why the city was spending potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight the suit instead of putting the money toward more shelter beds or homeless services.

In the course of the one-hour event organized by the shelter, the two candidates, competing in a runoff election on Tuesday, heard plenty more about the issue. One person said there was a misconception that all homeless people are drug addicts. A veteran said he had $771 left over from his disability check each month but couldn’t find a room for less than $500, and asked what he was supposed to do.

Even before the answers, everyone knew who the room was for. Lauren McLean, the City Council president and top vote-getter in an inconclusive November election, opposes the city’s quest for leeway in policing the homeless. She says the solution should come from tackling poverty.

“Each of us, no matter our situation, has to sleep,” she said. “We need more beds. We need to create homes for our residents.”

Her opponent, Mayor David Bieter, seeking his fifth term, was unapologetic about fighting the lawsuit, despite the shelter crowd. Echoing the position of various Western cities that support Boise’s stand, Mr. Bieter argued that the ability to issue citations for sleeping outside is a little-used but necessary tool to keep homelessness in check.

“I’m really concerned when I see Seattle or Portland or San Francisco,” he said. “I go there and I see a city that’s overwhelmed by the problem, and people tell me all the time, ‘Don’t allow us to be like those other cities.’”

On the surface, Boise, a city of about 230,000 whose modest downtown does little to obscure the mountain views, is an odd point of origin for such a debate. Its annual homeless counthas found about 50 to 100 unsheltered people for the past seven years. A drive around town turned up a handful of people sleeping outside, a far cry from the blocklong tent cities in California.

But the city’s decision to appeal Boise v. Martin has elevated homelessness to a focus of an increasingly ugly campaign. Third-party mailers have put Ms. McLean’s picture next to a homeless encampment with the words, “Lauren McLean’s Future Boise.” She recently posted on Facebook that someone in a pickup truck was putting tents and sleeping bags next to “McLean for Boise” yard signs.

The city’s relatively modest homeless problem is cited by both candidates to bolster their positions. Each is essentially campaigning on the idea that rapid growth needn’t produce streets of destitution as it has in California — but the two diverge on the role that law enforcement should play.

To Mr. Bieter, the homeless crises in Los Angeles and San Francisco prove that the city’s power to issue citations and shoo sleeping people off sidewalks is needed to prevent larger camps from forming.

Ms. McLean calls for a different approach. “I think other cities got to the point where it was too late,” she said in an interview. “So let’s say right now we’re actually going to get to work to prevent homelessness instead of hanging our hat on getting the right to ticket people.”

The road to the Supreme Court’s doorstep began in the office of Howard Belodoff, a Boise civil rights lawyer. In 2009, after a local shelter closed, Mr. Belodoff filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of six homeless men and women who had been cited for violating city ordinances that prohibit sleeping on public property. Most of the plaintiffs were prosecuted and pleaded guilty, with the exception of Robert Martin, whose case was dismissed.

Mr. Martin and the other plaintiffs subsequently filed suit challenging the constitutionality of the city’s ordinances. The case was litigated for several years before being appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Last year, in a decision that reverberated across the West Coast, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional to cite someone for sleeping outdoors if there wasn’t any shelter available.

In August, Boise formally asked the Supreme Court to hear the case. While the Ninth Circuit has described its decision as “narrow,” the city’s petition portrays it as anything but, using words like “vast,” “far-reaching” and “catastrophic” to depict a picture of mass confusion and lawlessness arising from the court’s ruling. The filing goes on to say that the Ninth Circuit’s ruling could also imperil a host of other public health laws “such as those prohibiting public defecation and urination.”

“Public encampments, now protected by the Constitution under the Ninth Circuit’s decision, have spawned crime and violence, incubated disease and created environmental hazards that threaten the lives and well-being both of those living on the streets and the public at large,” it declares.

In an interview, Ms. Evangelis, from Gibson Dunn, said: “I don’t think that fighting for someone’s right to live and die in squalor is helping.”

In response, lawyers for the plaintiffs, quoting an earlier Ninth Circuit decision, argue that the court’s ruling in the Boise case merely “reflects the ought-to-be uncontroversial principle that a person may not be charged with a crime for engaging in activity that is simply ‘a universal and unavoidable consequence of being human.’”

Dozens of cities have filed briefs backing Boise’s position, saying that they are confused as to how broadly the Ninth Circuit ruling applies and that the decision has impeded enforcement of basic health and safety laws. In some cases, the cities contend, the decision has actually made it harder to build housing meant for the homeless.

Among Boise’s allies is Los Angeles, which has passed more than $1 billion in bonds for permanent supportive housing but has found steep neighborhood resistance. Mike Feuer, the Los Angeles city attorney, said the Ninth Circuit decision raised as many questions as it answered. For instance, to determine whether or not is in compliance with the ruling, does the city have to constantly count how many beds there are and compare it to the homeless population? Can Los Angeles prohibit sleeping in sensitive locations, such as next to new homeless shelters?

“The language, rather than citing clear principles where constitutional questions are at stake, makes local jurisdictions vulnerable to lawsuits as they struggle to achieve a balance between the legitimate rights and interests of homeless people and the legitimate rights and interests of other residents and businesses,” he said.

Whatever happens in the Boise mayor’s race, Boise v. Martin is far enough along that its fate now rests with the Supreme Court: Even if she is elected mayor, Ms. McLean said, she has no plans to withdraw from the case. “The case is moving forward — that ship has sailed,” she said. “I just still maintain that we can do this without ticketing folks and moving them into the criminal justice system, which will make it harder to find shelter, home and work.”

#

Leave a Reply