Lead on.

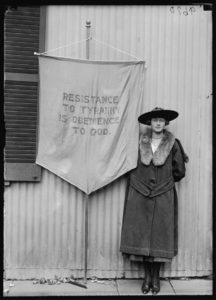

On the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage, it is worth considering what suffragists were fighting for, why they had to fight so hard, and who, exactly, was fighting against them.

-Margaret Talbot, The New Yorker

The Imperfect, Unfinished Work of Women’s Suffrage

A century after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, it’s worth remembering why suffragists had to fight so hard, and who was fighting against them.

In 1872, Susan B. Anthony’s attempt to vote and her subsequent arrest got the lion’s share of publicity, but Ware uses a carte de visite of the black activist Sojourner Truth to tell the story of how she, too, tried to vote in the Presidential election that year. A cookbook published as a fund-raiser by the Washington Equal Suffrage Association leads Ware to the story of one of its contributors, Cora Smith Eaton King, a physician and avid climber, who, with a recreational group called the Mountaineers, planted a “Votes for Women” banner at the summit of Mt. Rainier. Ware prefaces a reading of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist writings with a photograph of Gilman’s death mask, whose ghostly visage haunts a discussion of her lesser-known anti-immigrant and pro-eugenics politics. Alongside a front page of the Woman’s Exponent, one of the first women’s-media outlets west of the Mississippi—it was published, in Salt Lake City, from 1872 until 1914—Ware recounts the life of a contributor, Emmeline Wells, who advocated on behalf of women’s rights and the Mormon doctrine of plural marriage. (“Polygamy gives women more time for thought, for mental culture, more freedom of action, a broader field of labor,” she wrote.) A ballot box from Illinois appears with an account of the pioneering black women’s Alpha Suffrage Club, whose founder, the investigative journalist Ida Wells-Barnett, forcibly integrated the Woman Suffrage Procession—the original Women’s March—in 1913, after her white colleagues tried to segregate their protest of Woodrow Wilson’s Inauguration. “Either I go with you or not at all,” Wells-Barnett declared.

“I am not taking this stand because I personally wish for recognition. I am doing it for the future benefit of my whole race.”

The idea that women were always going to get the right to vote in the United States ignores the reality that they only got that right in Switzerland in 1971 and in Saudi Arabia in 2015. It also fails to explain why the right was granted to American women in 1920, as opposed to 1919 or 1918, or, perhaps more pointedly, 1776. Worse, the feeling of inevitability also conveys a sense of irreversibility, as if history always advances, and never stalls, or regresses.

Disenfranchisement can take many forms, and its most insidious manifestations are regrettably common: purging voter rolls, passing voter-identification requirements, understaffing or closing polling places, gerrymandering voting districts. Under the circumstances, perhaps the best way to celebrate the anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment is to remember all those who cannot vote, not only those who can. ♦

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/07/08/the-imperfect-unfinished-work-of-womens-suffrage

Leave a Reply