Because it’s not personal. And a caste system is a structure that we have inherited, that we did not create, that we don’t — there’s no point in pointing fingers about it, but it’s something that we — recognizing it is the first step toward dismantling it.

‘caste system, the artificial hierarchy’

You cannot diagnose a problem until you know the history of the problem that you’re trying to resolve.

The heart is the last frontier.

They were forced to seek political asylum within the borders of their own country because they were living in a caste system in the South that did not recognize their citizenship. And some of them travelled farther than current day immigrants might, but that was really not the point. The point was that the country actually was kind of two countries in one, and that’s what they had to do.

[…]

It’s about freedom and how far people are willing to go to achieve it. This is the means that they feel they must take in order to find freedom wherever they can find it.

[…]

George Swanson Starling. You asked him what he hoped for in leaving, and he said, “I was hoping I would be able to live as a man and express myself in a manly way” — I’m getting chills — “without the fear of getting lynched at night.”

[…]

These were refugee camps created in our American cities. And as they sought to expand, or if they managed to save whatever they could from these jobs — and a lot of them, new research about the Great Migration is coming out showing that they actually worked multiple jobs.

So they were actually making more money, but it wasn’t going as far because there were so many coming in, flooding these neighborhoods that were being hemmed in and pressed against. And that was the world that they had entered. They were living in the Vice Districts. I mean, all of the things that make for every possible disadvantage that you can have going in — that’s what they were facing.

Your existence, by definition, prohibited you from getting a standard mortgage. And so they would then get mortgages on the second market — secondary market which meant they were paying exorbitant rates. This is sounding very much like 2006 and 2007 for us now. And so this is all setting in motion all of these forces that were making it even more difficult for people to succeed in these big places, the cities of refuge for the people of the Great Migration.

[…]

[…]

Because, ultimately, what this migration was — and I think people are identifying it — is that it’s an unleashing of this pent-up creativity and genius, in many cases, of people miscast in this caste system.

You think about those cotton fields, and those rice plantations, and those tobacco fields, and on all of those cotton fields, and tobacco plantations, and rice plantations were opera singers, and jazz musicians, and poets, and professors, defense attorneys, doctors — I mean, that’s — this is the manifestation of the desire to be free and what was lost to the country. Because for centuries, for 246 years of enslavement — and I have to remind people — 12 generations of enslavement, 12 generations of enslavement. How many “greats” do you add to “grandparent” to get that back to 1619 until 1863? And that gives you a sense of how long all of these people were miscast into an artificial hierarchy as to what they were permitted to do, or risk death if they did not do that.

And one fact about this whole idea of where we are right now just sort of cosmically, I think, in terms of this — let me put it this way: no adult alive today will live to see a time when the time of enslavement was equal to the time of freedom. And so that shows you that this history is long, and the history is deep.

[…]

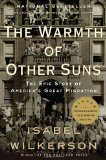

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. It is, hands down, the best work of nonfiction I have ever read. It tells the story of how the Jim Crow laws and their accompanying attitudes shaped the lives of three black Americans who came north during the 20th century. When I was reading it, I kept saying over and over again” — just like — “‘I had no idea. I had no idea.’”

And then, “We may be clueless and awkward around the subject of race, but we know what the Gospel demands. That we keep working at being better neighbors.” I think about that so much these days, about this work of knowing our neighbors who are strangers, and that that, in fact, is the immediate work that, in fact, is not evident how we do it because we’re so segregated in so many ways in our communities, but it’s possible. People must ask you this question. I wonder how — if there’s advice you give or thoughts you — that’s terrible — or thoughts you have about this work of coming to know our neighbors who are strangers, of being neighbors, just that.

[…]

I also believe that, in the time of working on this book — it’s multi-disciplinary. There’s sociology, there’s psychology, there’s economics. All of these things are in there. But I think the foundation of all of those disciplines comes down to the history. When you go to the doctor, before you can even see the doctor, the very first thing they do is they give you all of these pages to fill out. And they — before the doctor will even see you, he wants to know your history. He doesn’t want to know just your history, he wants to know your mother’s history. He wants to know your father’s history. They may go back to your grandmother and your grandfather on both sides. And that’s before he will even see you. You cannot diagnose a problem until you know the history of the problem that you’re trying to resolve.

[…]

“Over the decades, perhaps the wrong questions have been asked about the Great Migration. Perhaps it is not a question of whether the migrants brought good or will so the cities they fled to or were pushed or pulled to their destinations, but a question of how they summoned the courage to leave in the first place or how they found the will to press beyond the forces against them and the faith in a country that had rejected them for so long. By their actions, they did not dream the American Dream, they willed it into being by a definition of their own choosing. They did not ask to be accepted but declared themselves the Americans that perhaps few others recognized but that they had always been deep within their hearts.”

[…]

Our country is like a really old house. I love old houses. I’ve always lived in old houses. But old houses need a lot of work. And the work is never done. And just when you think you’ve finished one renovation, it’s time to do something else. Something else has gone wrong.

And that’s what our country is like. And you may not want to go into that basement, but if you really don’t go into that basement, it’s at your own peril. And I think that whatever you are ignoring is not going to go away. Whatever you’re ignoring is only going to get worse. Whatever you’re ignoring will be there to be reckoned with until you reckon with it. And I think that that’s what we’re called upon to do where we are right now.

[…]

I came to believe and to know that we all have so much more in common than we’ve been led to believe and that we’ve been sadly, tragically assigned roles as if we’re in a play, and this is what these people do, and this is what these people do, and this is what these people do. And the tragedy is that, regardless of which assignment that you had been put into, that might not have been your strength at all.

Every time I talk about it, I gain new appreciation and gratitude and amazement at what they were able to do. One of the things that I hope to do was to bring invisible people into the light. They never were being written about.

http://www.onbeing.org/program/isabel-wilkerson-the-heart-is-the-last-frontier/9043

[photo: A group of migrants from Florida rest near Shawboro, North Carolina on their way to work on a potato farm in Cranberry, New Jersey. July 1940. Jack Delano, photographer/Library of Congress]

Leave a Reply