Because it’s not personal. And a caste system is a structure that we have inherited, that we did not create, that we don’t — there’s no point in pointing fingers about it, but it’s something that we — recognizing it is the first step toward dismantling it.

Isabel Wilkerson

Isabel Wilkerson

January 21, 2021“Just now starting to realize the emotional toll, the psychic weight we have carried, what it does to the spirit to hold your breath for this long.”

Newspapers this morning from around the country, January 21st, 2021.

President Biden and First Lady Dr. Jill Biden watch fireworks from the balcony of their new home last night.

Photo: Tom Brenner/Reuters

Racial Privilege and Chords of Memory

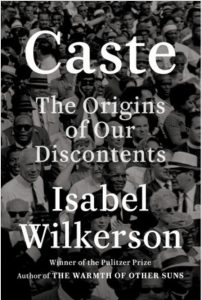

July 7, 2020Isabel Wilkerson’s follow-up to The Warmth of Other Suns will be released on August 20th.

She wrote an essay on July 1st for the New York Times called,

America’s Enduring Caste System

Our founding ideals promise liberty and equality for all. Our reality is an enduring racial hierarchy that has persisted for centuries.

[link]

“[Caste] should be at the top of every American’s reading list.”—Chicago Tribune

“As we go about our daily lives, caste is the wordless usher in a darkened theater, flashlight cast down in the aisles, guiding us to our assigned seats for a performance. The hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality. It is about power—which groups have it and which do not.”

‘In this brilliant book, Isabel Wilkerson gives us a masterful portrait of an unseen phenomenon in America as she explores, through an immersive, deeply researched narrative and stories about real people, how America today and throughout its history has been shaped by a hidden caste system, a rigid hierarchy of human rankings.

Beyond race, class, or other factors, there is a powerful caste system that influences people’s lives and behavior and the nation’s fate. Linking the caste systems of America, India, and Nazi Germany, Wilkerson explores eight pillars that underlie caste systems across civilizations, including divine will, bloodlines, stigma, and more. Using riveting stories about people—including Martin Luther King, Jr., baseball’s Satchel Paige, a single father and his toddler son, Wilkerson herself, and many others—she shows the ways that the insidious undertow of caste is experienced every day. She documents how the Nazis studied the racial systems in America to plan their out-cast of the Jews; she discusses why the cruel logic of caste requires that there be a bottom rung for those in the middle to measure themselves against; she writes about the surprising health costs of caste, in depression and life expectancy, and the effects of this hierarchy on our culture and politics. Finally, she points forward to ways America can move beyond the artificial and destructive separations of human divisions, toward hope in our common humanity.

Beautifully written, original, and revealing, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents is an eye-opening story of people and history, and a reexamination of what lies under the surface of ordinary lives and of American life today.’ [Amazon]

From writer Eula Biss, posted on Dec. 2, 2015.

White Debt

Reckoning with what is owed–and what can never be repaid–for racial privilege.

[link]

The word for debt in German also means guilt.

Only something that continues to hurt stays in the memory,’’ Nietzsche observes in ‘On the Genealogy of Morality.’

The power to punish, Nietzsche notes, can enhance your sense of social status, increasing the pleasure of cruelty.

“I read several hundred pages of ‘‘Little House on the Prairie’’ to my 5-year-old son one day when he was home sick from school. Near the end of the book, when the Ingalls family is reckoning with the fact that they built their little house illegally on Indian Territory, and just after an alliance between tribes has been broken by a disagreement over whether or not to attack the settlers, Laura watches the Osage abandoning their annual buffalo hunt and leaving Kansas. Her family will leave, too. At this point, my son asked me to stop reading. ‘‘Is it too sad?’’ I asked. ‘‘No,’’ he said, ‘‘I just don’t need to know any more.’’ After a few moments of silence, he added, ‘‘I wish I was French.’’

The Indians in ‘‘Little House’’ are French-speaking, so I understood that my son was saying he wanted to be an Indian. ‘‘I wish all that didn’t happen,’’ he said. And then: ‘‘But I want to stay here, I love this place. I don’t want to leave.’’ He began to cry, and I realized that when I told him ‘‘Little House’’ was about the place where we live, meaning the Midwest, he thought I meant it was about the town where we live and the house we had just bought. Our house is not that little house, but we do live on the wrong side of what used to be an Indian boundary negotiated by a treaty that was undone after the 1830 Indian Removal Act. We live in Evanston, Ill., named after John Evans, who founded the university where I teach and defended the Sand Creek massacre as necessary to the settling of the West. What my son was expressing — that he wants the comfort of what he has but that he is uncomfortable with how he came to have it — is one conundrum of whiteness.

‘‘Tell me again about the liar who lied about a lie,’’ my son said recently. It took me a moment to register that he meant Rachel Dolezal. He had heard me talking about her with Noel Ignatiev, author of ‘‘How the Irish Became White.’’ I had said: ‘‘She might be a liar, but she’s a liar who lied about a lie. The original fraud was not hers.’’ Because I was talking to Noel, who sent me to James Baldwin’s essay ‘‘On Being White … and Other Lies’’ when I was in college, I didn’t have to clarify that the lie I was referring to was the idea that there is any such thing as a Caucasian race. Dolezal’s parents had insisted to reporters that she was ‘‘Caucasian’’ by birth, though she is not from the Caucasus region, which includes contemporary Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. Outside that context, the word ‘‘Caucasian’’ is a flimsy and fairly meaningless product of the 18th-century pseudoscience that helped invent a white race.

Whiteness is not a kinship or a culture. White people are no more closely related to one another, genetically, than we are to black people. American definitions of race allow for a white woman to give birth to black children, which should serve as a reminder that white people are not a family. What binds us is that we share a system of social advantages that can be traced back to the advent of slavery in the colonies that became the United States. ‘‘There is, in fact, no white community,’’ as Baldwin writes. Whiteness is not who you are. Which is why it is entirely possible to despise whiteness without disliking yourself.

When he was 4, my son brought home a library book about the slaves who built the White House. I didn’t tell him that slaves once accounted for more wealth than all the industry in this country combined, or that slaves were, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, ‘‘the down payment’’ on this country’s independence, or that freed slaves became, after the Civil War, ‘‘this country’s second mortgage.’’ Nonetheless, my overview of slavery and Jim Crow left my son worried about what it meant to be white, what legacy he had inherited. ‘‘I don’t want to be on this team,’’ he said, with his head in his hands. ‘‘You might be stuck on this team,’’ I told him, ‘‘but you don’t have to play by its rules.’’

Even as I said this, I knew that he would be encouraged, at every juncture in his life, to believe wholeheartedly in the power of his own hard work and deservedness, to ignore inequity, to accept that his sense of security mattered more than other people’s freedom and to agree, against all evidence, that a system that afforded him better housing, better education, better work and better pay than other people was inherently fair.

My son’s first week in kindergarten was devoted entirely to learning rules. At his school, obedience is rewarded with fake money that can be used, at the end of the week, to buy worthless toys that break immediately. Welcome to capitalism, I thought when I learned of this system, which produced, that week, a yo-yo that remained stuck at the bottom of its string. The principal asked all the parents to submit a signed form acknowledging that they had discussed the Code of Conduct with their children, but I didn’t sign the form. Instead, my son and I discussed the civil rights movement, and I reminded him that not all rules are good rules and that unjust rules must be broken. This was, I now see, a somewhat unhinged response to the first week of kindergarten. I know that schools need rules, and I am a teacher who makes rules, but I still want my son to know the difference between compliance and complicity.”

‘Books change your mind.’

June 3, 2020“Where is our collective pain supposed to go when there’s no justice?”

-Wes Moore

The Aspen Institute

“Books are a form of political action. Books are knowledge. Books are reflection. Books change your mind.”

— Toni Morrison

‘At Aspen Words, we stand with all those fighting racism and injustice. We believe that words, sentences, and stories can lead to shifts in consciousness, to action and to change. Now and always, we hope you will join us in reading, following, sharing, and supporting black authors and poets whose works shine a spotlight on the structural racism and injustice in society. Here are just a few contemporary writers doing vital work through a variety of genres.’

#MustRead

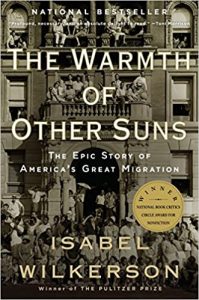

‘Pulitzer Prize–winning author Isabel Wilkerson chronicles one of the great untold stories of American history: the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South for northern and western cities, in search of a better life.

From 1915 to 1970, this exodus of almost six million people changed the face of America. Wilkerson compares this epic migration to the migrations of other peoples in history. She interviewed more than a thousand people, and gained access to new data and official records, to write this definitive and vividly dramatic account of how these American journeys unfolded, altering our cities, our country, and ourselves.’

‘caste system, the artificial hierarchy’

November 23, 2016You cannot diagnose a problem until you know the history of the problem that you’re trying to resolve.

The heart is the last frontier.

They were forced to seek political asylum within the borders of their own country because they were living in a caste system in the South that did not recognize their citizenship. And some of them travelled farther than current day immigrants might, but that was really not the point. The point was that the country actually was kind of two countries in one, and that’s what they had to do.

[…]

It’s about freedom and how far people are willing to go to achieve it. This is the means that they feel they must take in order to find freedom wherever they can find it.

[…]

George Swanson Starling. You asked him what he hoped for in leaving, and he said, “I was hoping I would be able to live as a man and express myself in a manly way” — I’m getting chills — “without the fear of getting lynched at night.”

[…]

These were refugee camps created in our American cities. And as they sought to expand, or if they managed to save whatever they could from these jobs — and a lot of them, new research about the Great Migration is coming out showing that they actually worked multiple jobs.

So they were actually making more money, but it wasn’t going as far because there were so many coming in, flooding these neighborhoods that were being hemmed in and pressed against. And that was the world that they had entered. They were living in the Vice Districts. I mean, all of the things that make for every possible disadvantage that you can have going in — that’s what they were facing.

Your existence, by definition, prohibited you from getting a standard mortgage. And so they would then get mortgages on the second market — secondary market which meant they were paying exorbitant rates. This is sounding very much like 2006 and 2007 for us now. And so this is all setting in motion all of these forces that were making it even more difficult for people to succeed in these big places, the cities of refuge for the people of the Great Migration.

[…]

[…]

Because, ultimately, what this migration was — and I think people are identifying it — is that it’s an unleashing of this pent-up creativity and genius, in many cases, of people miscast in this caste system.

You think about those cotton fields, and those rice plantations, and those tobacco fields, and on all of those cotton fields, and tobacco plantations, and rice plantations were opera singers, and jazz musicians, and poets, and professors, defense attorneys, doctors — I mean, that’s — this is the manifestation of the desire to be free and what was lost to the country. Because for centuries, for 246 years of enslavement — and I have to remind people — 12 generations of enslavement, 12 generations of enslavement. How many “greats” do you add to “grandparent” to get that back to 1619 until 1863? And that gives you a sense of how long all of these people were miscast into an artificial hierarchy as to what they were permitted to do, or risk death if they did not do that.

And one fact about this whole idea of where we are right now just sort of cosmically, I think, in terms of this — let me put it this way: no adult alive today will live to see a time when the time of enslavement was equal to the time of freedom. And so that shows you that this history is long, and the history is deep.

[…]

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. It is, hands down, the best work of nonfiction I have ever read. It tells the story of how the Jim Crow laws and their accompanying attitudes shaped the lives of three black Americans who came north during the 20th century. When I was reading it, I kept saying over and over again” — just like — “‘I had no idea. I had no idea.’”

And then, “We may be clueless and awkward around the subject of race, but we know what the Gospel demands. That we keep working at being better neighbors.” I think about that so much these days, about this work of knowing our neighbors who are strangers, and that that, in fact, is the immediate work that, in fact, is not evident how we do it because we’re so segregated in so many ways in our communities, but it’s possible. People must ask you this question. I wonder how — if there’s advice you give or thoughts you — that’s terrible — or thoughts you have about this work of coming to know our neighbors who are strangers, of being neighbors, just that.

[…]

I also believe that, in the time of working on this book — it’s multi-disciplinary. There’s sociology, there’s psychology, there’s economics. All of these things are in there. But I think the foundation of all of those disciplines comes down to the history. When you go to the doctor, before you can even see the doctor, the very first thing they do is they give you all of these pages to fill out. And they — before the doctor will even see you, he wants to know your history. He doesn’t want to know just your history, he wants to know your mother’s history. He wants to know your father’s history. They may go back to your grandmother and your grandfather on both sides. And that’s before he will even see you. You cannot diagnose a problem until you know the history of the problem that you’re trying to resolve.

[…]

“Over the decades, perhaps the wrong questions have been asked about the Great Migration. Perhaps it is not a question of whether the migrants brought good or will so the cities they fled to or were pushed or pulled to their destinations, but a question of how they summoned the courage to leave in the first place or how they found the will to press beyond the forces against them and the faith in a country that had rejected them for so long. By their actions, they did not dream the American Dream, they willed it into being by a definition of their own choosing. They did not ask to be accepted but declared themselves the Americans that perhaps few others recognized but that they had always been deep within their hearts.”

[…]

Our country is like a really old house. I love old houses. I’ve always lived in old houses. But old houses need a lot of work. And the work is never done. And just when you think you’ve finished one renovation, it’s time to do something else. Something else has gone wrong.

And that’s what our country is like. And you may not want to go into that basement, but if you really don’t go into that basement, it’s at your own peril. And I think that whatever you are ignoring is not going to go away. Whatever you’re ignoring is only going to get worse. Whatever you’re ignoring will be there to be reckoned with until you reckon with it. And I think that that’s what we’re called upon to do where we are right now.

[…]

I came to believe and to know that we all have so much more in common than we’ve been led to believe and that we’ve been sadly, tragically assigned roles as if we’re in a play, and this is what these people do, and this is what these people do, and this is what these people do. And the tragedy is that, regardless of which assignment that you had been put into, that might not have been your strength at all.

Every time I talk about it, I gain new appreciation and gratitude and amazement at what they were able to do. One of the things that I hope to do was to bring invisible people into the light. They never were being written about.

http://www.onbeing.org/program/isabel-wilkerson-the-heart-is-the-last-frontier/9043

[photo: A group of migrants from Florida rest near Shawboro, North Carolina on their way to work on a potato farm in Cranberry, New Jersey. July 1940. Jack Delano, photographer/Library of Congress]