Compassion among the homeless.

NPR/Fresh Air

Tues., Sept. 29th, 2015

http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=444214320

In this excerpt, Dr. O’Connell shares a story of a homeless woman, in need of a liver transplant, who makes an unusual, and tender request:

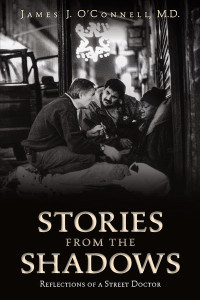

“Stories From The Shadows: Reflections Of A Street Doctor.”

GROSS:You have treated a lot of patients who have died – not necessarily died under your care directly, but eventually died from living on the street. And you write about how some of the shelters do funeral services or memorial services. And I would like you to describe one of the funerals that you’ve attended for a homeless person who you treated that you found especially moving.

O’CONNELL: One woman who was from the streets who used to describe herself as a bag lady. And she would keep you and I away by having just the smelliest clothes she could. And her belongings were smelly, and she would put those around her so that it would protect her from anyone coming near her. And she developed – she drank and had gotten hepatitis C from a blood transfusion many years ago, and she needed a liver transplant. And it turns out if you’re homeless, you have a very hard time getting a life-saving liver transplant unless you can show at least six months of residential stability and at least six months of being clean and sober. So we kept her in our facility for that time so that the transplant surgeons could have the documentation they needed. And I remember just before she was at the top the list, she called me over one Sunday morning and asked if I would take her picture. And I was not used to taking pictures of people’s faces at that time. I used to take pictures of, you know, feet – frostbitten feet, et. cetera – that I can use for teaching medical students and residents how to handle some of those problems. But I took a picture and brought it back to her. She got all dressed up – put on a dress, put lipstick on, tied her hair up. She had a Styrofoam cup in which she put some flowers and put it next to her bedside table. And I took the picture, and I brought it back to her a couple of days later in a little frame and asked her what was going on. And she told me that she was facing this major liver transplantation, didn’t know whether she’d live or die, but that she had not seen her daughters – two daughters – since they were 4 and 5 years old, and that was 25 years ago. And she wanted to be sure there was a picture of her in case her two daughters wanted to look and see what their mother – what had happened to their mother someday, and she wanted to be presentable. So I was blown away mostly because she was telling me – I think in graphic ways – what it’s like to experience illness, suffering and the specter of death when you are homeless and have lost everything. And what I have learned about homelessness in our city and I think across America that it is about as lonely a situation as you can have. People are alone, ignored, kind of abandoned. And I think when they face death, they look at their lives and wonder, you know, what could’ve been – think about what could have been, wonder about stuff. And I shudder every time I think about what that must be like to really have lost even touch with your own children, have no family members, have no money and really no hope for a future that looks any better than living on the streets. But anyway, what was striking to me is when I came back into – I gave her that picture when I came back to – our McInnis House is what we call it – I think there were 22 people the next day that asked me to take their portraits. And it’s…

GROSS: You have a lot of these photos in your book. Is that – so this is how you started doing that?

O’CONNELL: That’s exactly how I started doing it. I was always – I thought it was being kind of voyeuristic to take pictures of homeless people. I didn’t want to take advantage of the privilege I had of being in their lives to also take pictures, so I was kind of – it’s all upside-down from what I would’ve once thought. But that was a long-winded way of saying that death – when people die, we really try hard to mark their death and to gather people around and celebrate and memorialize these folks. Many, as you know, we don’t know where their families are. We don’t know if that was even their real name. And when they die, they’re in the morgue – the city morgue – until someone claims them. And if no one does, then they will be buried in a pauper’s grave somewhere in the city, so we try hard to not only one – try to find the families – but two – if no family is found, make sure we have a memorial and mark the burial and passage of that person. And it’s the other homeless people who really cherish and value that.

GROSS: So let me ask you, this – this photo that got you started taking pictures of the homeless patients that you treat, she wanted the photo taken so if she died, her daughters who she had lost touch with would see what their mother looked like.

O’CONNELL: Yes.

GROSS: Did anyone come looking for her?

O’CONNELL: No one ever came.

GROSS: That must have made you sad.

O’CONNELL: It did. It was really sad.

Leave a Reply