Yegor Zhukov

‘Responsibility & Love’

December 7, 2019The New Yorker

By Masha Gessen

[Yegor Zhukov’s message about responsibility and love at his trial, for “extremism,” shows what political resistance can be and seems to describe American reality as accurately as the Russian one.]

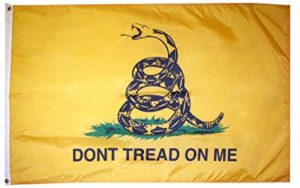

I was going to write a column about Wednesday’s impeachment hearing, about the way it once again showcased the two non-overlapping realities into which American politics has split. But then I caught up on another hearing that took place on Wednesday, this one in a Moscow court. A twenty-one-year-old university student named Yegor Zhukov stood accused of “extremism,” for posting YouTube videos in which he talked about nonviolent protest, his campaign for a seat on the Moscow City Council, and different approaches to political power. In his most recent video, recorded four months ago, he suggested that “madmen” like Vladimir Putin view power as an end in itself, while political activists view it as an instrument of common action. In many of his vlog entries, Zhukov is seated against the backdrop of the Gadsden flag—“Don’t Tread on Me”—which appears to hang in his bedroom in his parents’ apartment.

The prosecutor had asked for four years of prison time for Zhukov. On Friday, a Moscow court sentenced Zhukov to three years’ probation—an unusually light punishment probably explained by the public response to Zhukov’s speech, which several Russian media outlets dared to publish. Hundreds of people gathered in front of the courthouse on the day of the sentencing. As a condition of his probation, Zhukov is banned from posting to the Internet. The judge also ordered that the flag, which was confiscated by police, be destroyed.

Instead of writing my own column, I have translated Zhukov’s final statement, delivered in court on Wednesday. I did it because it is a beautiful text that makes for instructive reading. Parts of it seem to describe American reality as accurately as the Russian one. Parts of it show what resistance can be. All of it, I hope, will make readers think twice before they use the word “Russians” to mean goons. I also hope it will serve as a reminder of what we miss while we are—rightly—obsessed with American politics, which is made more provincial every day by its isolationist President and the need to try to reduce the harm he causes. As for the column I was going to write, I will still have plenty of opportunities to write it, while the very young man who spoke the following words will be unable to publish for the next three years.

“This court hearing is concerned primarily with words and their meaning. We have discussed specific sentences, the subtleties of phrasing, different possible interpretations, and I hope that we have succeeded at showing to the honorable court that I am not an extremist, either from the point of view of linguistics or from the point of view of common sense. But now I would like to talk about a few things that are more basic than the meaning of words. I would like to talk about why I did the things I did, especially since the court expert offered his opinion on this. I would like to talk about my deep and true motives. The things that have motivated me to take up politics. The reasons why, among other things, I recorded videos for my blog.

“But first I want to say this. The Russian state claims to be the world’s last protector of traditional values. We are told that the state devotes a lot of resources to protecting the institution of the family, and to patriotism. We are also told that the most important traditional value is the Christian faith. Your Honor, I think this may actually be a good thing. The Christian ethic includes two values that I consider central for myself. First, responsibility. Christianity is based on the story of a person who dared to take up the burden of the world. It’s the story of a person who accepted responsibility in the greatest possible sense of that word. In essence, the central concept of the Christian religion is the concept of individual responsibility.

“The second value is love. ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’ is the most important sentence of the Christian faith. Love is trust, empathy, humanity, mutual aid, and care. A society built on such love is a strong society—probably the strongest of all possible societies.

“To understand why I’ve done what I’ve done, all you have to do is look at how the Russian state, which proudly claims to be a defender of these values, does in reality. Before we talk about responsibility, we have to consider what the ethics of a responsible person is. What are the words that a responsible individual repeats to himself throughout his life? I think these words are, ‘Remember that your path will be difficult, at times unbearably so. All your loved ones will die. All your plans will go awry. You will be betrayed and abandoned. And you cannot escape death. Life is suffering. Accept it. But once you accept it, once you accept the inevitability of suffering, you must still accept your cross and follow your dream, because otherwise things will only get worse. Be an example, be someone on whom others can depend. Do not obey despots, fight for the freedom of body and soul, and build a country in which your children can be happy.’

“Is this really what we are taught? Is this really the ethics that children absorb at school? Are these the kinds of heroes we honor? No. Our society, as currently constituted, suppresses any possibility of human development. [Fewer than] ten per cent of Russians possess ninety per cent of the country’s wealth. Some of these wealthy individuals are, of course, perfectly decent citizens, but most of this wealth is accumulated not through honest labor that benefits humanity but, plainly, through corruption.

“An impenetrable barrier divides our society in two. All the money is concentrated at the top and no one up there is going to let it go. All that’s left at the bottom—and this is no exaggeration—is despair. Knowing that they have nothing to hope for, that, no matter how hard they try, they cannot bring happiness to themselves or their families, Russian men take their aggression out on their wives, or drink themselves to death, or hang themselves. Russia has the world’s [second] highest rate of suicide among men. As a result, a third of all Russian families are single mothers with their kids. I would like to know: Is this how we are protecting the institution of the family?