Trees for Jane

A million trees by 2030.

October 2, 2021When you donate to Trees for Jane or plant your own tree, you will receive a digital certificate in recognition of your simple but essential contribution to helping our planet become green again!

Each certificate will include your name, donation or tree registration date, and a personal serial number used to track global participation. Each certificate will also be electronically signed by Jane.

OUR MISSION

“Our global mission is to help everyone to support broad-scale community-based forest protection and restoration efforts. We also want to inspire individuals of all walks of life, everywhere, to plant and care for their own trees.

Our mission is aligned with the United Nations’ Decade on Ecosystem Restoration initiative and the Trillion Tree Campaign with 1t.org—a global call to action to protect and restore one trillion trees by 2030.”

“Planting one tree might seem like a small thing to do as we face such an enormous crisis. But Trees for Jane believes that everyone can make a difference. You plant one tree, but then thousands, maybe millions more like you around the world do the same—it all adds up to a more healthy and sustainable planet.

Beyond helping to save the climate and the environment, planting trees can be good for personal health, especially in urban areas where trees provide shade, beauty, joy, and many other benefits. Planting and caring for a tree can also be a great way to connect to nature.

Trees, like all living creatures, require ongoing care. And on a social level, tree planting can bring people together, serve to commemorate a special occasion, or be an excellent gift for someone special.”

#TreesForJane

Tree Planting Guide

UPWORTHY

These organizations are planting trees to combat the “urban heat island effect” in Richmond

America’s urban areas are often known as concrete jungles due to their abundance of asphalt and lack of parks and natural grassy areas. These neighborhoods are often populated by low-income, communities of color because of discriminatory lending practices known as redlining. These policies, which date back to the 1930s, were put in place to reinforce racial segregation and reallocate city funds to white neighborhoods.

Redlining policies perpetuated inequality that was not only economic but environmental as well.

The buildings, roads, and unnatural infrastructure that make up urban areas absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes. This turns urbanized areas into “heat islands” that experience warmer temperatures than greener, less populated neighborhoods.

Richmond, Virginia’s urban heat islands can reach temperatures as much as 20 degrees warmer than the greener areas of the city. Heat islands look to become an even greater problem in the coming years as extreme temperature shifts caused by climate change become more common.

To help create green space in heat-island communities, Capital One is supporting the Arbor Day Foundation and Groundwork RVA with $75,000 in grant funding to plant and distribute roughly 300 trees in affected neighborhoods across Richmond.

“Greenspace and access to fresh food [are] vital to the communities we serve. We are proud to work with Groundwork RVA and the Arbor Day Foundation to help address those needs here in Richmond,” said Andrew Green, Director of Capital One’s Office of Environmental Sustainability.

Together, the three organizations will strive to improve green infrastructure in three areas that have been identified as some of the hottest, least-resourced in Richmond.

This is just one isolated reason as to why we need to…must…plant trees. -dayle

WBUR Boston

Sandy Brook in the Bobryk forest, which sits between Sandisfield and New Marlborough, Mass. in the Berkshires. (Courtesy Markelle Smith/The Nature Conservancy)

“In the big scheme of things, the Bobryk forest is pretty small potatoes. It’s about 300 acres of birch, hemlock and other hardwood trees, sandwiched between two larger state forests in western Massachusetts.

“It feels weird to say this forest isn’t special because that’s not what I mean,” says Laura Marx, a forest ecologist at The Nature Conservancy in Massachusetts. Rather, says Marx, Bobryk forest is “a really cool example” of things gone right, and an illustration of exactly how preserving forests might help slow climate change.

When the privately owned forest went on the market in 2020, The Nature Conservancy, the Berkshire Natural Resources Council and the state of Massachusetts put Bobryk forest into conservation to protect it from development.

That means that about 136,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide already stored in the trunks and roots of Bobryk trees stayed there, says Marx. And each year going forward, the trees should remove and store another 190 metric tons of carbon dioxide. That’s roughly equal to the emissions of 58 cars and trucks.

Sandy Brook in the Bobryk forest, which sits between Sandisfield and New Marlborough, Mass. in the Berkshires. (Courtesy Markelle Smith/The Nature Conservancy)

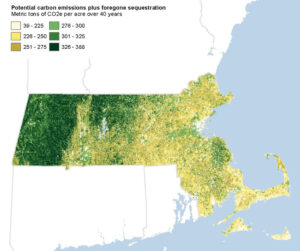

Marx drew these numbers from a report released Tuesday that attempts to quantify exactly how much carbon dioxide could be kept out of the sky by preserving forests in the region.

The report by researchers at Clark University, called “Avoided Deforestation: A Climate Mitigation Opportunity in New England and New York,” provides hard numbers for officials trying to hit their climate goals — for instance, Massachusetts’ ambitious plan to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

[…]

Massachusetts is losing about 5,000 acres of forest each year, according to Mass Audubon. That’s an area about half the size of Provincetown cut down, mostly for housing developments, commercial sites and solar farms. By doing this, the state adds the equivalent of about 1.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year.

“In the state of Massachusetts, that’s equal to 2% of the state’s fossil fuel emissions across all sectors in the year 2018,” says study author Christopher Williams, a professor in Clark University’s Graduate School of Geography. “Even though it’s only 5,000 acres per year, it still adds up.”

Map of “carbon consequences.” If any given point on the map is deforested, the map shows the net carbon dioxide emission equivalents over the next 40 years. (Courtesy The Nature Conservancy)