totalitarianism

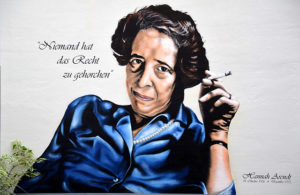

Hannah Arendt

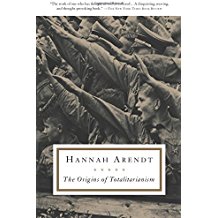

July 28, 2018“She wrote in her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism, going on to elaborate that this “mixture of gullibility and cynicism… is prevalent in all ranks of totalitarian movements”:

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

“The great analysts of truth and language in politics”—writes McGill University political philosophy professor Jacob T. Levy—including “George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, Vaclav Havel—can help us recognize this kind of lie for what it is…. Saying something obviously untrue, and making your subordinates repeat it with a straight face in their own voice, is a particularly startling display of power over them. It’s something that was endemic to totalitarianism.”

Arendt and others recognized, writes Levy, that “being made to repeat an obvious lie makes it clear that you’re powerless.” She also recognized the function of an avalanche of lies to render a populace powerless to resist, the phenomenon we now refer to as “gaslighting”:

The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end—is being destroyed.

Arendt’s analysis of propaganda and the function of lies seems particularly relevant at this moment. The kinds of blatant lies she wrote of might become so commonplace as to become banal. We might begin to think they are an irrelevant sideshow. This, she suggests, would be a mistake.

Open Culture, Michiko Kakutani