The Gospel

…”damaging to the Gospel.”

November 4, 2019Josh Harris: Evangelical support for Trump “incredibly damaging to the Gospel”

[Josh Harris, once one of America’s most famous evangelical pastors, admitted in his first interview since renouncing Christianity that he ruined lives and marriages, so he excommunicated himself from the faith that made him famous.- AXIOS]

Asked how much of a connection he sees between the fundamentalist doctrine of fear and the current political climate, Harris replied: “Fear is easily manipulated by political leaders. The more chaotic the world is, the more people want someone to tell them what to do. And when people are afraid, they latch on to people who say, ‘I have the answers.’ […] I don’t think it’s going to end well. To have a leader like DT is part of the indictment. This is the leader you want and deserve; it represents a lot of who you are.”

The gospel of giving.

September 10, 2018Exploiting tax codes in the name of philanthropy.

“For every foundation that existed in 1930, there are now five hundred.”

Just Giving: Why Philanthropy is Failing Democracy and How It can Do Better,

Rob Reich, Stanford political science professor

David Callahan:

“It’s not just that the megaphones operated by 5019c0(3) groups and financed by a sliver of rich donors have gotten louder and louder, making it harder for ordinary citizens to be heard. These citizens are helping foot the bill.

When it comes to who gets heard in the public square ordinary citizens can’t begin to compete with an activist donor classes. How many very rich people need to care intensely about a cause to finance megaphones that drown out the voices of everyone else? Not many.”

Gospels of Giving For the New Gilded Age/Are today’s donor classes solving problems, or creating new ones?

By, Elizabeth Kolbert

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/gospels-of-giving-for-the-new-gilded-age

Kolbert:

The idea that both liberals and conservatives are exploiting the tax code is small consolation.

In the spring of 1889, Andrew Carnegie published an essay on money. If possession confers knowledge, then there was no greater expert on the subject: Carnegie was possibly the richest American who ever lived.

The “Gospel” opened with a discussion of inequity. This was the Gilded Age, and, even as most Americans were struggling to get by, the one-per-centers were putting up “cottages” in Newport. The disparity was, in Carnegie’s view, unavoidable. It was the price of progress, and progress, ultimately, benefitted everyone.

“The Gospel of Wealth” has been called the “ur-text of modern philanthropy.” It advocated a new kind of giving, a form of charity that wasn’t charity but something more pragmatic and, at the same time, more ambitious—a giving aimed, in Carnegie’s words, at improving “the general condition of the people.” Acting on his own advice, Carnegie went on to endow Carnegie Hall, the Carnegie Foundation, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now part of Carnegie Mellon University), and more than twenty-five hundred local libraries. His contemporaries financed the Rockefeller Foundation, the Russell Sage Foundation, the Field Museum, and the University of Chicago.

The “Gospel” also prompted the ur-critiques of philanthropy. In 1890, the Reverend Hugh Price Hughes, a Methodist minister, wrote that, while he was sure Carnegie was “a most estimable and generous man,” his “Gospel” represented a “social monstrosity” and a “grave political peril.” William Jewett Tucker, a professor of religion who would later become the president of Dartmouth, was no less horrified. What the “Gospel” advocated, Tucker wrote, was “a vast system of patronage,” and nothing could “in the final issue create a more hopeless social condition.” To assume that “wealth is the inevitable possession of the few” was to evade the essential issue: “The ethical question of today centres, I am sure, in the distribution rather than in the redistribution of wealth.”

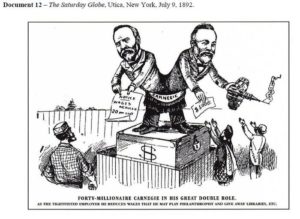

To critics, the Homestead strike made explicit the inconsistency of Carnegie’s position. How could a person ruthlessly exploit his employees and, at the same time, claim to be a benefactor of the toiling masses? The Saturday Globe, a Utica-based weekly, published a cartoon showing two Carnegies, conjoined at the hip. One, smiling, handed out a library and a check; the other held out a notice telling workers that their pay had been slashed. “As the tight-fisted employer he reduces wages that he may play philanthropist,” the caption read.

It is difficult to say what fraction of philanthropic giving goes toward shaping public policy. Callahan estimates that the figure is somewhere around ten billion dollars a year. Such an amount, he says, might not sound huge, but it’s more than the annual contributions made to candidates, parties, and super-pacs combined. The result is doubly undemocratic. For every billion dollars spent on advocacy tricked out as philanthropy, several hundred million dollars in uncaptured taxes are lost to the federal treasury.

Instead of promoting equality, Reich worries, tax subsidies for philanthropy may actually be doing the reverse. He cites, in particular, local-education foundations, or lefs. These are, essentially, souped-up PTAs, formed to supplement public-school budgets, and they’ve grown dramatically in recent years. Some lefs raise only enough money to buy paint sets or musical instruments, but some, in more affluent districts, raise thousands of dollars a pupil. In the town of Hillsborough, California, just north of Stanford, Reich reports, parents of public-school students get a letter at the start of the year asking for a contribution of twenty-three hundred dollars for each child enrolled. While the contributing parents can’t dictate exactly how the money will be spent, Reich writes, it’s easy to imagine groups of parents pressing the district to hire specialized teachers or to purchase sophisticated equipment that “can be targeted to benefit their own children.” This arrangement, in his view, exacerbates existing inequities in school funding, and, since contributions to lefs are tax deductible, rich districts are, in effect, receiving a subsidy from other taxpayers.

The New Yorker/The Mail

Sept. 10, 2018:

As someone who is working to elect a Democrat in a Republican-held congressional district, I asked myself why none of the philanthropists mentioned in Kolbert’s article are working to protect the most basic mechanism of democracy: the right to vote. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, forty-one states have outdated voting machines that are vulnerable to hacking and breakdowns. Officials in thirty-three states told researchers that they didn’t have enough funds to upgrade their systems before 2020. If Silicon Valley is happy to sell voting systems to the government, shouldn’t tech billionaires feel some responsibility for safeguarding them and fixing them, since hacking threatens the liberal, free-market democracy that enabled their companies to succeed in the first place? My first thought upon finishing Kolbert’s article was: Will anyone rescue our democracy with a funds-for-secure-elections drive? Because the federal government hasn’t done so, and apparently won’t.

Sharona Muir

Perrysburg, Ohio