shootings

‘What are we going to do?’

July 9, 2016Emphasis on ‘we.’ This is a sentiment, ‘What are we going to do?’ that is being shared again and again after our nation’s week of heartbreak, confusion, frustration, anger, fear, pain, and sorrow. Deep sorrow. Many posts and articles I have read often start with the same words: ‘I don’t know how to express how I am feeling.’

(Interfaith prayer vigil in Dallas the morning after the shootings.)

For the third time in as many days, President Obama has made public comments in response to our nation’s shock and sorrow. Today he said from Poland, ‘We cannot let the actions of a few define all of us’ and that the ‘human responsible for killing five Dallas police officers does not represent black Americans any more than a white man accused of killing blacks at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, represents whites (AP).

When he first learned of the attack, his social media comment from the White House was that he was ‘deeply disturbed.’ My initial reaction to these words were of course, we are all deeply disturbed. What now? What? So many are asking what can we do? Enough. We are hurting. And we want to do something.

“If you are a normal, white American, the truth is you don’t understand being black in America and you instinctively under-estimate the level of discrimination and the level of additional risk.”

-Newt Gingrich (R), Former US Representative

Author Michelle Alexander writes:

“In recent years, I have come to believe that truly transformative change depends more on thoughtful creation of new ways of being than reflexive reactions to the old. What is happening now is very, very old. We have some habits of responding to this familiar pain and trauma that are not serving us well. In many respects it’s amazing that we endure at all. I am inspired again and again by so much of the beautiful, brilliant and daring activism that is unfolding all over the country. Yet I also know that more is required than purely reactive protest and politics. A profound shift in our collective consciousness must occur, a shift that makes possible a new America.

I know many people believe that our criminal justice system can be “fixed” by smart people and smart policies. President Obama seems to think this way. He suggested yesterday that police-community relations can be improved meaningfully by a task force he created last year. Yes, a task force. I used to think like that. I don’t anymore. I no longer believe that we can “fix” the police, as though the police are anything other than a mirror reflecting back to us the true nature of our democracy. We cannot “fix” the police without a revolution of values and radical change to the basic structure of our society. Of course important policy changes can and should be made to improve police practices. But if we’re serious about having peace officers — rather than a domestic military at war with its own people— we’re going to have to get honest with ourselves about who our democracy actually serves and protects.”

My sentiments echoes her’s. A task force? Really? We are so far beyond needing yet another task force. When my daughter’s college recently was dealing with unrest regarding social inequalities and racial frustrations, the president decided to cancel classes one day a schedule a day of ‘inclusion.’ There was a microphone. There were a few speakers, but mostly it was a chance for everyone to congregate and share…vent…express. It was cathartic. This day of inclusion is to become an annual event. To check in. Push the ‘pause’ button. Connect.

Maybe we need one of these in our country. Everybody just stop. Nobody goes to work. Nobody goes to school. We all meet in our neighborhoods, our communities and talk. Share. Express. Embrace. Weep. And name our fears. We ask the difficult questions. We acknowledge our sense of ‘other.’ This happened in our country immediately following the terrorists attacks on 9/11 – – until we were invited to ‘go shopping’ (President George W. Bush). And then war. And we lost a timely opportunity to unite and change.

The white police officer in Minnesota who killed the young black man in his car was seemingly petrified with fear after the shooting. He couldn’t move, or drop his gun. His voiced seemed distraught with what he had done, and didn’t know what to do, or how to proceed, his voice violent with emotion.

The girlfriend who was seemingly calm enough to share the event live via social media, was told not to move…to keep her hands where they were…as your young daughter observed, and absorbed, every word and action in the backseat of the car. And while her boyfriend moaned in agony. Until he was silent.

I have thought so much about this woman. How could she remain so calm? I would be crazed. Weeping. Screaming. And it occurred to me as I have been reading Isabel Wilkerson’s book, The Warm of Other Suns/The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, that quite possibly what she had just observed were similar scenarios to those she has observed again and again in her culture and community. Reportedly, her boyfriend who was shot and killed, had been stopped 31 times and charged with more than 60 minor violations – resulting in thousands of dollars in fines – before his last, fatal encounter with the police http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3679678/Man-shooting-death-hand-cop-streamed-live-pulled-31-times-charged-63-times-officers-near-home.html.

As a nation, we are seemingly are able to show unity and prayer in the aftermath of tragedies. It isn’t long before we fall back into our lives, our political ideologies, and our short news cycles with ‘hashtags’ and rants. This time, though, the words are embedded with a plea for action. I heard it in the words at the interfaith prayer vigil in downtown Dallas, blocks away from where President Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963. All creeds and ethnicities were represented. Even watching on television, the energy, the empathy and compassion were palpable.

I heard an interview today, Saturday, July 9th, (NPR) with Poet Claudia Rankine. She spoke about Timothy McVey (Oklahoma City bombing) and Micah Johnson (Dallas shootings) who she said seem to be ‘cut of the same cloth.’ Both had served in the military, and both knew how to deliver carnage with their expertise, weapons, and training, for war.

I mean, you know, for me, Micah Johnson and Timothy McVeigh are not very different. They’re both war vets who were clearly unstable in a certain way and trained in the use of guns. And, you know, why somebody was able to have an automatic gun in their home – I’m not sure why that’s possible.

But in any case, those two gentlemen are the – you know, they’re cut from the same cloth, but in no way does Johnson represent black people in America. And, you know, what we’ve seen with the police is that black people have been seen as one person. And so consequently their level of vengeance against what they assume to be the black body as a criminal body allows them to behave in a way that costs the lives of innocent people. http://www.npr.org/2016/07/09/485356173/poet-claudia-rankine-on-latest-racial-violence

One white. One black. Both angry. And both disenfranchised from their society and country. Where was the disconnect? How do we mend and reach out to those who have lost connection to their humanity to stop senseless carnage and loss?

Author and journalist George Sanders recently said that the only tool we have is ‘empathy.’ Interesting. Can we teach to empathy? What about compassion? Can we teach compassion? Is compassion, or empathy, a natural law?

Harvard Social Ethics professor Mahzarin Banaji spoke to Krista Tippet recently on her podcast, On Being, and shared she prefers the word ‘understanding’ to tolerance. How do we learn to understand each other? How do we move beyond our implicit biases, generations of racist DNA, to seek understanding? She has co-written a new book called, Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People, and she is the co-founder of the implicit bias research organization Project Implicit. She says,

‘The good people is extremely important to me. I do believe that we have changed over the course of our evolutionary history into becoming better and better people who have higher and higher standards for how we treat others. And so we are good. And we must recognize that, and yet, ask people the question, “Are you the good person you yourself want to be?” And the answer to that is no, you’re not. And that’s just a fact. And we need to deal with that if we want to be on the path of self-improvement.’

Self-improvement, I offer, is defined as ‘understanding’ of other.

I am a big Krista Tippet fan, read all of her books, including her latest, Becoming Wise.

I have learned so much from her over the many years I have listened to her radio show and podcasts. She is often the starting point for study and research in my dissertation program at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. She is brilliant and truly a gifted communicator.

Recently, she re-aired a dialogue she had with John A. Powell, a legal scholar and director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at the University of California at Berkeley. He’s previously taught in Africa and across the United States.

She spoke with Powell in 2015 in Minneapolis before a live audience. This has been an especially difficult time for Tippet – – the shooting in Minneapolis took place only a block away from her home. Powell speaks to race, which he equates to gravity, meaning, a very ‘heavy’ topic for many people to face and discuss. His mother and father where sharecroppers in the South and his father is a Christian Minister.

“Scientists say there are probably twelve people in the world that really understand gravity. And I would say there’s only a few more in the world that understand race. But it’s actually incredibly complex once we start peeling it back. I’m old enough to have been born colored. And then I became a negro. And then I became black. And then I became African-American. And then I became afro. And people are just now confused, like, so what are we? You know?And part of the confusion — and each of those terms are significant. But also, race is deeply relational. And it’s interesting if you go back and think about how whiteness was early defined in America. It was defined largely as not black. And so, James Baldwin reminds us that blackness is in whiteness, that whiteness is in blackness, that these are these complicated dances, these — that we — most of us don’t understand.”

[…]

I remember being 12 years old in Detroit. He, like most people from the South, he did everything himself. So, he’s fixing the furnace, and it blew up. It cindered all the hair on his body, so he had burns all over his body. We’re driving around the city trying to find a hospital who would accept a black man and getting turned away, and then going on to the next hospital, getting turned away. And as I tell these stories, again, they are sad stories. But when you meet my dad, he just radiates love. I mean, he literally attracts people. And he has this quality of appreciating life, and I feel like a little of that has fallen to me. My interest in social justice — I don’t know where it comes from, really, except I would say part of it’s the family. Part of it’s — to me, it’s an expression of caring, just caring about people and saying that you are connected to people in other life forms and then giving it voice. And I think if we do that, we not only lean into what’s called social justice, but deeply into spirituality and religion as well.

[…]

So when we talk about the appropriation of Native American land or when we talk about slavery, we’re not talking about the history of black people, we’re talking about the history of this country.

And Toni Morrison made the observation. She said we’ve had all of these studies on what the institution of slavery has done to mark the black identity. She says it’s about time we look at what it’s done to mark the white identity. It’s America. That’s what slavery is about. It’s about America. And I don’t care if you came here last week or ten days ago, you can’t understand this country without understanding the institution of slavery. It was pivotal.”

US Representative John Lewis (D-Ga), who marched and organized during the Civil Rights Movement, often speaks, as did Martin Luther Kind, Jr., to the ‘beloved community.’ In the context of social alchemy he asks, “What if the beloved community were already a reality? A true reality? And we embodied it before everyone else could see it? He reiterates again and again, we need to teach peace and live non-violence. And to visualize a ‘beloved community.’

We need the ability to have uncomfortable conversations between races and cultures. We need to understand our implicit, or un-conscious biases. Does this happen through policy? Mandates from our government? Or from our communities and each other?

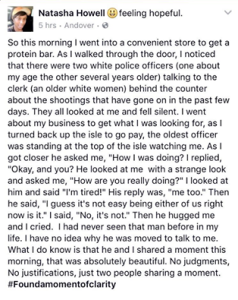

Posted recently on social media:

We cannot have these conversations if we do not connect with each other and ask the tough questions. The questions that seemingly make us vulnerable and uncomfortable.

What are communities doing now? How are we making connections locally?

The City of Seattle has budgeted funds to explore and research implicit bias in their community and police force, training some 10,000 citizens.

In Baltimore, volunteers are working together in a program called ‘Thread’ to change the social fabric of their community by mentoring high school students who are failing school and displaying destructive behaviors. Volunteers commit to work with students over a 10 year period of time. Hundreds of students have been guided and encouraged to find their sense of purpose of contribution. http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/07/09/484053257/prove-that-struggling-high-students-can-succeed

Powell shares an anecdote from a community in Oak Park, Illinois:

“So Oak Park is in Chicago. Chicago’s one of the most segregated areas in the country. Cook County has the largest black population of any county in the United States, and a lot of studying of segregation takes place in Chicago. So here you have Oak Park, this precious little community. And they were liberal whites there, and blacks started moving in. And they were saying, “Look, we actually don’t mind blacks moving in, but we’re concerned that we’re going to lose the value of our home. That’s the only wealth we have. And if we don’t sell now, we’re going to lose.” And it basically said, “If that’s the real concern, not that blacks are moving in, that you’re going to lose the value of your home, what if we were to ensure that you would not lose the value of your home? We’ll literally create an insurance policy that the value of your home — we will compensate you if the value of your home goes down.” And they put that in place.

[…]

Think about Katrina. So these examples are all around us, and yet, we don’t tell stories about them. Katrina — the face of Katrina, when you remember it, it was blacks stuck on roofs as the water was rising. What’s not told is that Americans, all Americans, gave to those people. It was the largest civilian giving of one population to another in the history of the United States. So here you had white Americans, Latino-Americans, Asian-Americans trying to reach out to what they saw as black Americans. They were actually saying — they were claiming we have a shared humanity. And they actually did a poll asking people if they were willing to raise taxes to rebuild. 70 percent of Americans said, “Yes, we would tax ourselves to help those people.” The pundits and the politicians ignored it. And so that story simply didn’t get told. The fastest growing demographic in the United States, the fastest growing demographic in United States is not Latinos. It’s actually interracial couples and interethnic couples. That’s people themselves right now, not tomorrow, trying to imagine a different America, trying to say, “I can love anyone. I can be with anyone.”

There is a lot we can do, if we come together and have the conversations that our difficult to have. I am hopeful. No more task forces. We need to find a way to dialogue, to question, to understand in our own communities and neighborhoods.

Powell:

“People are looking for community. Right now, though, we don’t have confidence in love. You mentioned love earlier. We have much more confidence in anger and hate. We believe anger is powerful. We believe hate is powerful. And we believe love is wimpy. And so if we’re engaged in the world, we believe it’s much better to sort of organize around anger and hate. And yet, we see two of the most powerful expressions, certainly Gandhi, certainly the Reverend Dr. King — and I always remind people he was a reverend. It wasn’t just Dr. King. Even though he came out of a violent revolution — Nelson Mandela — he just — again, I met him personally — he just exuded love. And as you know, he had a chance to leave prison early. He refused to unless it included structuring the country. He actually tried to actually lean into a notion of beloved community. He actually didn’t want the blacks to control or dominate the whites. He wanted to create — so his aspiration — and he’s loved. Even today, he’s loved in South Africa, and he’s loved around the world.”

So I think part of it is that we don’t have to imagine doing things one at a time. And the other thing is that it’s not that we necessarily get there, but we claim life, our own and others. We actually celebrate and engage in life. And so, to me, it’s like — it’s not like, “How do we get there?” It’s like, “How do we live?”

‘…what we’re finding now in the last 30 years is that much of the work, in terms of our cognitive and emotional response to the world, happens at the unconscious level.

We move from race, the discussion of race — it was partially because we were trying to move from the Jim Crow era and the white supremacy era. And we said, “OK, that’s bad.” So to notice race is bad, so let’s not notice it anymore.’

[…]

The human condition is one about belonging. We simply cannot thrive unless we are in relationship. I just gave a lecture on health. And if you’re isolated, the negative health condition is worse than smoking, obesity, high blood pressure — just being isolated.

[…]

So we need to be in relationship with each other. And so, when you look at what groups are doing, whether they are disability groups or whether they’re groups organized around race, they are really trying to make us — a claim of, “I belong. I’m a member.” So if you think about Black Lives Matter, it’s really just saying, “We belong.” How we define the other affects how we define ourselves.

Tippet’s foundational question:

‘We’re not defined by the worst that happens but we struggle to know how to rise to our best; so what if we opened the question of race to the question of belonging?’

Carolyn Myss believes we can be the change in our own communities simply by being a light. This light, she believes, is enough to create change. We lead by example in our language and our behaviors, allowing a sense of belonging.

Again, Powell:

‘We’re talking about what I call a circle of human concern, a circle of concern for all life, human life, and our planetary life.’

Michelle Alexander:

“I think we all know, deep down, that something more is required of us now. This truth is difficult to face because it’s inconvenient and deeply unsettling. And yet silence isn’t an option. On any given day, there’s always something I’d rather be doing than facing the ugly, racist underbelly of America. I know that I am not alone. But I also know that the families of the slain officers, and the families of all those who have been killed by the police, would rather not be attending funerals. And I’m sure that many who refused to ride segregated buses in Montgomery after Rosa Parks stood her ground wished they could’ve taken the bus, rather than walk miles in protest, day after day, for a whole year. But they knew they had to walk. If change was ever going to come, they were going to have to walk. And so do we.”