Roman Empire

Dangerous Ambiguities

February 10, 2020‘As a nation, we have begun to float off into a moral void, and all the sermons of all the priests in the country (if they preach at all) are not going to help much.

We have got to the point where the promulgation of any kind of moral standard automatically releases an anti-moral response in a whole lot of people. It is not with them, above all, that I am concerned but with the ‘good’ people, the right-thinking people, who stick to principle, all right, except where it conflicts with the chance to make money.

It seems to me that there are very dangerous ambiguities about our democracy in its actual present condition. I wonder to what extent our ideals are not a front for organized selfishness and systematic irresponsibility.

If our affluent society ever breaks down and the facade is taken away, what are we going to have left?

-Thomas Merton, 1961

Image credit: Anna Washington Derry (detail), Laura Wheeler Waring, 1927, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The vast majority of people throughout history have been poor, disabled, or oppressed in some way (i.e., “on the bottom”) and would have read history in terms of a need for change, but most of history has been written and interpreted from the side of the winners.

Every viewpoint is a view from a point.

We must be able to critique our own perspective if we are to see a fuller truth.

Liberation theology—which focuses on freeing people from religious, political, social, and economic oppression—is mostly ignored by Western Christianity. Perhaps that’s not surprising when we consider who interpreted the Scriptures for the last seventeen hundred years. The empowered clergy class enforced their own perspective instead of that of the marginalized, who first received the message with such excitement and hope. Once Christianity became the established religion of the Roman Empire (after 313), we largely stopped reading the Bible from the side of the poor and the oppressed. We read it from the side of the political establishment and the usually comfortable priesthood instead of from the side of people hungry for justice and truth. Shifting our priorities to make room for the powerless instead of accommodating the powerful is the only way to detach religion from its common marriage to power, money, and self-importance.

When Scripture is read through the eyes of vulnerability—what we call the “preferential option for the poor” or the “bias from the bottom”—it will always be liberating and transformative. Scripture will not be used to oppress or impress. The question is no longer, “How can I maintain the status quo?” (which just happens to benefit me), but “How can we all grow and change together?” Now we would have no top to protect, and the so-called “bottom” becomes the place of education, real change, and transformation for all.

Dorothy Day (1897–1980): “The only way to live in any true security is to live so close to the bottom that when you fall you do not have far to drop, you do not have much to lose.” [1] From that place, where few would expect or choose to be, we can be used as instruments of transformation and liberation for the rest of the world.

-Fr Richard Rohr

Dorothy Day, Loaves and Fishes: The Inspiring Story of the Catholic Worker Movement (Orbis Books: 1997), 86.

Decadent Cultures

What’s new:

The truth of the first decades of the 21st century, a truth that helped give us the Trump presidency but will still be an important truth when he is gone, is that we probably aren’t entering a 1930-style crisis for Western liberalism or hurtling forward toward transhumanism or extinction.

Instead, we are aging, comfortable and stuck, cut off from the past and no longer optimistic about the future, spurning both memory and ambition while we await some saving innovation or revelation, growing old unhappily together in the light of tiny screens.

Why it matters:

[T]rue dystopias are distinguished, in part, by the fact that many people inside them don’t realize that they’re living in one, because human beings are adaptable enough to take even absurd and inhuman premises for granted.

If we feel that elements of our own system are, shall we say, dystopia-ish — from the reality-television star in the White House to the addictive surveillance devices always in our hands; from the drugs and suicides in our hinterlands to the sterility of our rich cities — then it’s possible that an outsider would look at our decadence and judge it more severely still. [AXIOS]

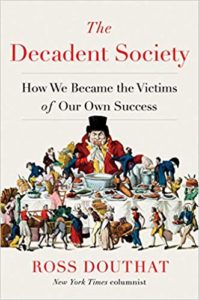

The Age of Decadence

Cut the drama. The real story of the West in the 21st century is one of stalemate and stagnation.

An Opinion columnist and the author of the forthcoming book “The Decadent Society,” from which this essay is adapted.

“…civilization has entered into decadence,” in the classic sense of the word — “a lack of resolution in the face of threats,” with “hints at exhaustion, finality.”

Following in the footsteps of the great cultural critic Jacques Barzun, we can say that decadence refers to economic stagnation, institutional decay and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development. Under decadence, Barzun wrote, “The forms of art as of life seem exhausted, the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result.” He added, “When people accept futility and the absurd as normal, the culture is decadent.” And crucially, the stagnation is often a consequence of previous development: The decadent society is, by definition, a victim of its own success.

Note that this definition does not imply a definitive moral or aesthetic judgment. (“The term is not a slur,” Barzun wrote. “It is a technical label.”) A society that generates a lot of bad movies need not be decadent; a society that makes the same movies over and over again might be. A society run by the cruel and arrogant might not be decadent; a society where even the wise and good can’t legislate might be. A crime-ridden society isn’t necessarily decadent; a peaceable, aging, childless society beset by flares of nihilistic violence looks closer to our definition.

Nor does this definition imply that decadence is necessarily an overture to a catastrophe, in which Visigoths torch Manhattan or the coronavirus has dominion over all. History isn’t always a morality play, and decadence is a comfortable disease: The Chinese and Ottoman empires persisted for centuries under decadent conditions, and it was more than 400 years from Caligula to the actual fall of Rome.

“What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman Empire is not that it finally went smash,” wrote W.H. Auden of that endless autumn, but rather that “it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth, or hope.”

[…]

Close Twitter, log off Facebook, turn off cable television, and what do you see in the Trump-era United States? Campuses in tumult? No: The small wave of campus protests, most of them focused around parochial controversies, crested before Trump’s election and have diminished since. Urban riots? No: The post-Ferguson flare of urban protest has died down. A wave of political violence? A small spike, maybe, but one that’s more analogous to school shootings than to the political clashes of the 1930s or ’60s, in the sense that it involves disturbed people appointing themselves knights-errant and going forth to slaughter, rather than organized movements with any kind of concrete goal.

The madness of online crowds, the way the internet has allowed the return of certain forms of political extremism and the proliferation of conspiracy theories — yes, if our decadence is to end in the return of grand ideological combat and street-brawl politics, this might be how that ending starts.

But our battles mostly still reflect what Barzun called “the deadlocks of our time” — the Kavanaugh Affair replaying the Clarence Thomas hearings, the debates over political correctness cycling us backward to fights that were fresh and new in the 1970s and ’80s. The hysteria with which we’re experiencing them may represent nothing more than the way that a decadent society manages its political passions, by encouraging people to playact extremism, to re-enact the 1930s or 1968 on social media, to approach radical politics as a sport, a hobby, a kick to the body chemistry, that doesn’t put anything in their relatively comfortable late-modern lives at risk.

Complaining about decadence is a luxury good — a feature of societies where the mail is delivered, the crime rate is relatively low, and there is plenty of entertainment at your fingertips. Human beings can still live vigorously amid a general stagnation, be fruitful amid sterility, be creative amid repetition. And the decadent society, unlike the full dystopia, allows those signs of contradictions to exist, which means that it’s always possible to imagine and work toward renewal and renaissance.

‘…thinking seriously about how to rebuild after DT leaves office, and how to create a political life that exists outside him and is not dependent on him as its source of terrible gravity.’

[full read]