Reparations

#MustListen

June 25, 2020NPR

A Call for Reparations: How America Might Narrow the Racial Wealth Gap

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones on the racial wealth gap — and why she believes it’s time for reparations. Her new piece published in New York Times magazine.

The killing of George Floyd has ignited protests and inspired conversations — and changes — across the globe. But New York Times Magazine writer Nikole Hannah-Jones says more needs to be done to address America’s racial wealth gap.

“Very few Americans have created all of their wealth on their own; it’s passed down through generations and then built upon,” Hannah-Jones says. “Black Americans never really had a chance to do that.”

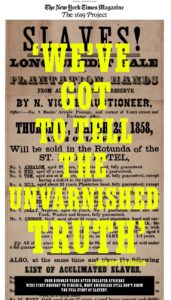

Hannah-Jones traces the wealth gap to slavery, and the fact that enslaved people were not allowed to own property. She notes that the legalized segregation and racial terrorism that followed slavery exacerbated the problem and “prevented generation after generation of Black Americans from acquiring the type of wealth or foothold in the economy that allows you to live a life that is much more typical of white Americans.”

Hannah-Jones won a Pulitzer Prize for creating the 1619 project at The New York Times, which tracks the legacy of slavery. Her latest article for the Times Magazine, What is Owed, makes the case for economic reparations for Black Americans.

Nikole Hannah-Jones:

Very few Americans have created all of their wealth on their own; it’s passed down through generations and then built upon. Black Americans never really had a chance to do that.

There are stories of mass starvation of Black people after they had been freed, having to leave the plantation and find shelter in burned out buildings, trying to forage for food in burned-out fields. It was a devastating period for Black people. This country decided that it was going to do nothing, that it owed these people nothing.

1619

August 14, 2019The N.Y. Times launches the 1619 Project, “observing the 400th anniversary of the beginning of American slavery.”

- Late August of 1619 “was when a ship arrived at Point Comfort in the British colony of Virginia, bearing a cargo of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans.”

- Why it matters: The project “aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.”

[NYTimes prescription needed to view full article…Dayle’s Community Cafe does not subscribe to for-profit/elitist journalism.]

The reparations plan.

Race Relations, Reconciliation and Reparations

At the time when slaves were first emancipated at the end of the Civil War, there are estimated to have been between 4 to 5 million enslaved persons in the American South. General Tecumseh Sherman promised to every former slave family of four, forty acres and a mule. While this would have provided a way to make a living and feed one’s family, integrating economically into life as a freed citizen, only a few actually received the acreage and among those who received it most had it then taken away.

As Martin Luther King, Jr. would ask a hundred years later, “They were freed, but what were they freed to?” It was a full hundred years after the end of the Civil War before the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 to dismantle segregation, and only in 1965 did the Voting Rights Act insure equal access to black people at the polls.

The issue of the economic gap that existed at the end of the Civil War, however, was never addressed beyond Sherman’s promise. And the gap has never been closed.

I have advocated for broad scale reparations for slavery since the 1990’s, and was the first candidate in this presidential primary season to make it a pillar of my campaign.

The issue of reparations is not a fringe notion. Germany has paid over $89 Billion to Jewish organizations since the end of WW2 and, while they do not erase the horror of the Holocaust, reparations have gone far towards establishing reconciliation between Germany and the Jews of Europe. Similarly, in 1988 Ronald Reagan signed the American Civil Liberties Act assigning between $20,000 to $22,000 to surviving prisoners of the Japanese internment camps during WW2. The idea that a people which has wronged another people should then pay economic restitution as payment for that wrong, is a civilized notion long considered reasonable.

#CivilObligation

July 4, 2019

Thursday, July 4, 2019

Sister Simone Campbell, SSS—known as “the nun on the bus”—is someone I consider a modern prophet. She is the Executive Director of NETWORK, an organization that lobbies for socially just federal policies. On this “Independence Day” (in the United States), reflect on Sr. Simone’s invitation to co-create our collective freedom.

In the last half of the twentieth century, thankfully, our society began to engage in a serious process of trying to atone for the sin of slavery, and in doing so much emphasis was placed on promoting civil rights. An unintended consequence of this important movement was a heightened focus on individuals and individual exercise of the freedoms guaranteed in the Constitution. The civil rights movement came out of community, but the legal expression focused on individuals’ capacity to exercise their freedoms. Some fearful Americans—largely white men who professed a conservative version of Christianity—felt threatened, as if there were not enough rights to go around. They sought to create their own “movement.” This reaction in part fueled the rise of the tea party movement. . . .

But a democracy cannot survive if various groups and individuals only pull away in different directions. Such separation will not guarantee that all are allowed the opportunity for “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” All people must be recognized for their inherent dignity and gifts regardless of the color of their skin, their religious beliefs, or their place of origin. And all these gifts need to be shared in order to build up the whole.

So I have begun to wonder if the new task of the first half of the twenty-first century should be a commitment to civil obligations as a balance to the focus on civil rights.

Civil obligations call each of us to participate out of a concern and commitment for the whole. Civil obligations call us to vote, to inform ourselves about the issues of the day, to engage in serious conversation about our nation’s future and learn to listen to various perspectives. To live our civil obligations means that everyone needs to be involved and that there needs to be room for everyone to exercise this involvement. This is the other side of civil rights. We all need our civil rights so that we can all exercise our civil obligations.

The mandate to exercise our civil obligations means that we can’t be bystanders who scoff at the process of politics while taking no responsibility. We all need to be involved. Civil obligations mean that we must hold our elected officials accountable for their actions, and we must advocate for those who are struggling to exercise their obligations. The 100 percent needs the efforts of all of us to create a true community.

It is an unpatriotic lie that we as a nation are based in individualism. The Constitution underscores the fact that we are rooted and raised in a communal society and that we each have a responsibility to build up the whole. The Preamble to the Constitution could not be any clearer: “We the People” are called to “form a more perfect Union.”

-Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation

Simone Campbell with David Gibson, A Nun on the Bus: How All of Us Can Create Hope, Change, and Community (HarperOne: 2014), 180-182.

Image credit: Frieze of the Prophets (detail), John Singer Sargent, circa 1892, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.