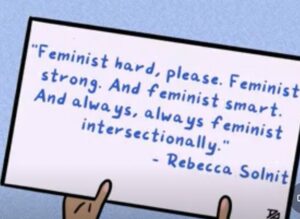

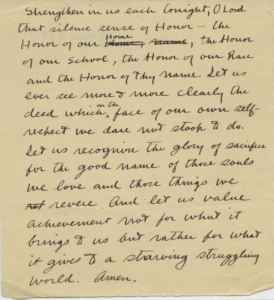

Rebecca Solnit

The New Yorker/Houston

MUST

L

I

S

T

E

N

Ezra Klein and Dahlia Lithwick, NYTimes podcast, ‘The Ezra Klein Show.’

The Dobbs Decision Isn’t Just About Abortion. It’s About Power.

The legal journalist Dahlia Lithwick breaks down the Dobbs decision and considers the “raw power” of the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority.

I’m Ezra Klein. This is “The Ezra Klein Show.”

On Friday, June 24, a Supreme Court majority voted to overturn Roe v Wade. I am recording this on Saturday evening, and abortion is now banned in at least nine states. More likely to follow in the coming days. The way to understand this moment goes beyond any one case. This is a moment of legal regime change. This has made clearest in a concurring opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts. He charges — it’s really an extraordinary document. He charges the other five Republican appointees with abandoning judicial restraint. He writes quote, “If it is not necessary to decide more to dispose of a case, then it is necessary not to decide more.”

Perhaps we’re not always perfect and following that command, and certainly, there are cases that warrant an exception, but this is not one of them. There are now six Republican appointees on the Supreme Court to three Democratic appointees. That is true despite Republicans losing the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections. The Supreme Court is our least Democratic branch, but it has become unbelievably undemocratic, maybe even anti-democratic.

[…]

I’m joined today by Dahlia Lithwick. She covers the Supreme Court for Slate, she hosts the legal podcast “Amicus.” she’s a person I turn to whenever I need to understand the court, and she brings her clarity and passion in spades here today. As always, my email is ezrakleinshow@nytimes.com.

[…]

Well, this is where we get back to that. I remember a couple of years ago, you and I chatted about this minoritarian rule problem that leaches its way not just through the filibuster, which means the WHPA, the Women’s Health Protection Act, didn’t even come to a vote that would have codified Roe or the filibuster rule, the John Lewis Act, which would have reinstated the parts of the Voting Rights Act that Shelby County gutted.

And I think that part of the thing that we need to really wrap our heads around is what do you do when Republicans currently sitting on the court were seated by presidents who, in fact, lost the popular vote but won the electoral college and the electoral college is massively weighted towards rural agrarian states and that in turn is reaffirmed by a Senate that massively, massively malapportioned in the interests of rural agrarian states. And they then, once they get on the court, become a party too exactly what you’re describing, which is shrinking the vote whether it’s Shelby County, or Brnovich last year.

Whatever it is, it feels as though this really does feel like the doom loop of minority rule right now.

Dahlia Lithwick’s three book recommendations:

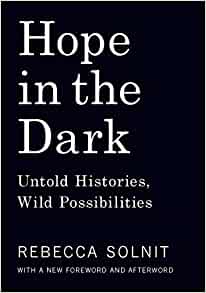

- Hope in the Dark – – “Profound meditation.”

- Man’s Search for Meaning – – “A lodestar to purpose.”

- You Can’t be Neutral on a Moving Train – – She quotes Zinn:

“To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives. If we see only the worst, it destroys our capacity to do something.

If we remember those times and places, and there are so many where people have behaved magnificently, this gives us the energy to act and at least the possibility of sending this spinning top of a world in a different direction. And if we do act in however smaller way, we don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents. And to live now as we think human beings should live in defiance of all that is bad around us is itself a marvelous victory.” Howard Zinn, “You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train.”

Full podcast:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/26/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-dahlia-lithwick.html

—

POLITICO

The Supreme Court dissenting opinion on Roe v. Wade

The dissent was authored by Justice Stephen Breyer.

“With sorrow — for this Court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection — we dissent.”

-Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan

Full text, 66 pages:

“Today’s Supreme Court decision is wrong.”

June 24, 2022“With sorrow — for this Court, but more, for the many millions of American women who have today lost a fundamental constitutional protection — we dissent.”

-Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan

❧

Progress isn’t always a straight line.

Today’s Supreme Court decision is wrong

but Congress passing the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act is a modest but real step forward. And the fight will go on, thanks to the activists, survivors, and families who continue to demand action.

Today, the Supreme Court not only reversed nearly 50 years of precedent, it relegated the most intensely personal decision someone can make to the whims of politicians and ideologues—attacking the essential freedoms of millions of Americans.

-President Barack Obama

♡ ‘Culture of Care’ @AnaMariaforNY

Timeline: America’s Long Civil Rights March

By Nikole Hannah-Jones and Al Shaw, ProPublica

[2013]

Ever since the War of the States, Congress and the Supreme Court have clashed over the question of civil rights. When considering the recent rulings on affirmative action, the Voting Rights Act and the Defense of Marriage Act, it is useful to take the long view of the push and pull between Congress and the Supreme Court when it comes to civil rights. The long arc of history might bend toward justice, but there’s always been a lot of pendulum swinging along the way.

https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/vra

GALLUP

WASHINGTON, D.C. — With the U.S. Supreme Court expected to overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision before the end of its 2021-2022 term, Americans’ confidence in the court has dropped sharply over the past year and reached a new low in Gallup’s nearly 50-year trend. Twenty-five percent of U.S. adults say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the U.S. Supreme Court, down from 36% a year ago and five percentage points lower than the previous low recorded in 2014.

Abortion is a fundamental right for all women. It must be protected. I wish to express my solidarity with the women whose liberties are being undermined by the Supreme Court of the United States.

-French President Emmanuel Macron

P

E

A

C

E

Non-violence.

K

I

N

D

The Kindness Bonus

Seth Godin

“Please be kind” sounds like a moral imperative. And in some ways, it is.

But behind the theory of the firm and a key building block of successful communities is the idea that kind interactions are significantly more productive.

When people feel seen and respected, they’re more likely to focus on what needs to be done, instead of taking umbrage or being defensive.

When we leave opportunities and pathways for others, they can move forward with less friction.

And when we’re enjoying our days, we’ve created a posture that spreads.

Hockey games aren’t supposed to be kind. But just about everything else works better when we don’t throw elbows.

“CARE is the antidote to violence.”

– Saidiya Hartman

From Jon Meacham’s podcast today, June 24th, 2022

On June 24th, 1990, The Catholic Church discusses excommunicating politicians who disagree with the church on abortion rights.

Important listen for history, and in this moment.

Reflections of History

From former Governor Mario Cuomo in 1984, at Notre Dame:

“I speak here as a politician and also as a Catholic, raised as a Catholic, pre-Vatican II church, educated in Catholic schools, attached to the church first by birth and then by choice, now by love. […] The Catholic church is my spiritual home. My heart is there. And my hope. The Catholic who holds political office in a pluralistic democracy, who was elected to serve Jews and Muslims, atheists, and protestants, as well as Catholics, bear special responsibility. He or she undertakes to help to create conditions under which all can live with a maximum of dignity and with a reasonable degree of freedom. Where everyone who chooses can hold beliefs different from specifically Catholic ones, sometimes contradictory to them, with laws that protect people’s rights to divorce, use birth control, and even to choose abortion. I protect my right to be a Catholic by preserving your right to believe as a Jew, a protestant, or non-believer, or anything else you choose. I accept the church’s teaching on abortion, must I insist you do, by law? By denying you Medicaid funding, by a Constitutional amendment? If so, which one? Would that be the best way to avoid abortions, or prevent them? […] We should understand whether abortion is outlawed or not, our work has barely begun. The work of creating a society where the right to life doesn’t end at the moment of birth. Where an infant isn’t helped into a world that doesn’t care if it’s fed properly, housed decently, educated adequately.”

“Search for the means of grace, and the hope of glory.” -Jon Meacham

S A N C T U A R Y

California Governor Gavin Newsom:

Abortion is legal in California.

It will remain that way.

I just signed a bill that makes our state a safe haven for women across the nation.

We will not cooperate with any states that attempt to prosecute women or doctors for receiving or providing reproductive care.

—

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

The news coming out of the United States is horrific. My heart goes out to the millions of American women who are now set to lose their legal right to an abortion. I can’t imagine the fear and anger you are feeling right now.

—

Signal App post today on twitter:

@signalapp

Here is your friendly reminder that we built Signal for private, secure communication. It’s built so you can communicate individually and in groups, through text and calls, without fear of interference or data collection. Free to use and not for profit.

#protectwomen

‘Dear neighbors…’

March 14, 2020Don’t forget: disasters and crises bring out the best in people

Rutger Bregman

“Dear neighbours. If you’re over 65 and your immune system is weak, I’d like to help you. Since I’m not in the risk group, I can help you in the coming weeks by doing chores or running errands. If you need help, leave a message by the door with your phone number. Together, we can make it through anything. You’re not alone!”

“We’ve learned how to accept help from others,” writes a woman living in Wuhan.“Because of this quarantine, we have bonded with and supported each other in ways that I’ve never experienced in nine years of living here.” Millions of Chinese people are encouraging each other to stand strong, using the Cantonese expression “jiayou” (“don’t give up”). YouTube videos show people in Wuhan singing from the windows of their homes, joined by numerous neighbours nearby, their voices rising in chorus and echoing amongst the soaring towers of Chinese cities. In Siena and Naples, both on complete lockdown, people are singing together from the balconies of their homes.

Children in Italy are writing “andrà tutto bene” (“everything will be all right”) on streets and walls, while countless neighbours are helping each other. On Thursday, an Italian journalist told the Guardian about what he had witnessed with his own eyes: “After a moment of panic in the population, there is now a new solidarity. In my community the drugstores bring groceries to people’s homes, and there is a group of volunteers that visit houses of people over 65.” A tour guide from Venice notes: “It’s human to be scared, but I don’t see panicking, nor acts of selfishness.”

The words “andrà tutto bene” – everything will be all right – were first used by a few mothers from the province of Puglia, who posted the slogan on Facebook. From there, it spread across the country, going viral almost as fast as the pandemic. The coronavirus isn’t the only contagion – kindness, hope and charity are spreading too.

As a species of animal that evolved to make connections and work together, it feels strange to suppress our desire for contact. People enjoy touching each other, and find joy in seeing each other in person – but now we have to keep our physical distance.

Still, I believe we can grow closer in the end, finding each other in this crisis. As Giuseppe Conte, the Italian prime minister, said this week: “Let’s distance ourselves from each other today so that we can embrace each other more warmly […] tomorrow.”

The pandemic has exposed how interconnected and interdependent we are as humans. Everyday practices, like handwashing and covering our sneezes, have become the most basic duty we owe to friends and strangers alike. And we’re finding thoughtful ways to care for another amidst the tumult.

Kristin Lin

Editor, The On Being Project

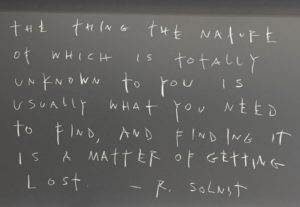

“Hope, for me, just means … coming to terms with the fact that we don’t know what will happen and that there’s maybe room for us to intervene.”

~Rebecca Solnit

“Great literature will come from this. Great art will come from this. Great awareness will come from this. Great love will come from this. More than anything else, great people will come from this – if we allow it to expand our hearts and minds.”

~Marianne Williamson

Seattle Times

Naomi Ishisaka

‘In the days since the Seattle area became the epicenter of the outbreak, the outpouring of support has been moving and inspiring. On an individual level, people have offered free babysitting, cooking and food delivery for harried parents and medically vulnerable older adults.

After racist coronavirus fears drove down business in Seattle’s Chinatown International District, Bill Tashima, a board member for the local Japanese American Citizens League, created a Facebook group on Sunday to share ways to support small restaurants. Within days, the group had nearly 5,000 members, sharing ideas for restaurant takeout to boost business in the struggling district and creating a virtual “tip jar” that one member was using to collect donations for restaurant workers.

The artistic community, which already experiences economic insecurity in good times due to unpredictable contract-based work, saw all public events canceled like dominoes in the past week. Seattle-area author Ijeoma Oluo quickly set up a GoFundMe on Monday to raise and distribute funds for artists. Within days, the fund raised $80,000 and distributed $10,000 and was in the process of distributing another $30,000 to artists directly impacted by loss of income due to the coronavirus. Another group of people started a live-performance streaming site on Facebook called “The Quarantine Sessions,” where artists can perform and the audience can tip the band before their performance starts.

To support those who are most vulnerable in an emergency, a grassroots effort formed in Seattle called “Covid19MutualAid,” centered on people with disabilities, people of color, undocumented people, older adults and others. In addition to recruiting volunteers for direct support such as food and grocery deliveries, the group is also advocating for systemic changes that would make communities less vulnerable in the first place.

When Seattle Public Schools announced Wednesday they would be closing abruptly the next day, people across the city jumped into action, knowing that for the 32% of Seattle school district families that are low income, school lunches are a critical part of how children stay fed. Volunteers and staff distributed school lunches for pickup at Highland Park Elementary in West Seattle on Thursday and in Rainier Beach, Washington Building Leaders of Change or WA-BLOC and food justice organization FEEST planned a free hot lunch called “Feed the Beach” for families on Friday with additional lunches twice a week after that.

These are just a few of the many grassroots efforts that are just getting started in our region. Larger entities like the Seattle Foundation are also taking action, with rapid response resources like the COVID-19 Response Fund quadrupling to $9 million in a few days.

The coming months will challenge us in ways we have never before imagined. But if we continue, as writer Sonya Renee Taylor said, to “put radical love into practice,” we might emerge stronger than we began.’

______

Editor’s note: The spread of novel coronavirus has left the state of Washington in a state of uncertainty. But amid the growing pandemic, members of the community have shown remarkable acts of kindness and efforts to take care of each other. From crowdsourced relief funds for local artists, to readers sending our own newsroom pizza after a long day, many people are rising to the occasion to uplift one another.

Boston Globe

Mattia Ferraresi is a writer for the Italian newspaper Il Foglio.

A message from Italy

‘So here’s my warning for the United States: It didn’t have to come to this.

We of course couldn’t stop the emergence of a previously unknown and deadly virus. But we could have mitigated the situation we are now in, in which people who could have been saved are dying. I, and too many others, could have taken a simple yet morally loaded action: We could have stayed home.

What has happened in Italy shows that less-than-urgent appeals to the public by the government to slightly change habits regarding social interactions aren’t enough when the terrible outcomes they are designed to prevent are not yet apparent; when they become evident, it’s generally too late to act. I and many other Italians just didn’t see the need to change our routines for a threat we could not see.

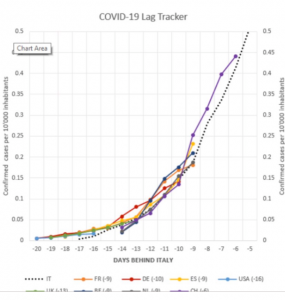

Italy has now been in lockdown since March 9; it took weeks after the virus first appeared here to realize that severe measures were absolutely necessary.

According to several data scientists, Italy is about 10 days ahead of Spain, Germany, and France in the epidemic progression, and 13 to 16 days ahead of the United Kingdom and the United States. That means those countries have the opportunity to take measures that today may look excessive and disproportionate, yet from the future, where I am now, are perfectly rational in order to avoid a health care system collapse. The United States has some 45,000 ICU beds, and even in a moderate outbreak scenario, some 200,000 Americans will need intensive care.

The way to avoid or mitigate all this in the United States and elsewhere is to do something similar to what Italy, Denmark, and Finland are doing now, but without wasting the few, messy weeks in which we thought a few local lockdowns, canceling public gatherings, and warmly encouraging working from home would be enough stop the spread of the virus. We now know that wasn’t nearly enough.

Life in lockdown is hard, but it is also an exercise in humility. Our collective well-being makes our little individual wishes look a bit whimsical and small-minded. My wife and I work from home, or at least we try to. We help the kids with their homework, following the instructions their teachers send every morning via voice messages and video, in a moving attempt to keep alive their relationships with their students.

Strangely, it’s also a moment in which our usual individualistic, self-centered outlook is waning a bit. In the end, each of us is giving up our individual freedom in order to protect everybody, especially the sick and the elderly. When everybody’s health is at stake, true freedom is to follow instructions.’

NYTimes

Eric Klinenberg, NYU Social Sciences Professor

‘It’s an open question whether Americans have enough social solidarity to stave off the worst possibilities of the coronavirus pandemic. There’s ample reason to be skeptical. We’re politically divided, socially fragmented, skeptical of one another’s basic facts and news sources. The federal government has failed to prepare for the crisis. The president and his staff have repeatedly dissembled about the mounting dangers to our health and security. Distrust and confusion are rampant. In this context, people take extreme measures to protect themselves and their families. Concern for the common good diminishes. We put ourselves, not America, first.

But crises can be switching points for states and societies, and the coronavirus pandemic could well be the moment when the United States rediscovers its better, collective self. Ordinary Americans, regardless of age or party, already have abundant will to promote public health and protect the most vulnerable. Although only a fraction of us are old, sick or fragile, nearly all of us love and care for someone who is.

Today Americans everywhere are worried about the fate of friends and family members. Without stronger solidarity and better leadership, though, millions of our neighbors may not get the support they need.

We’re not likely to get better leadership from the Trump administration, but there’s a lot we can do to build social solidarity. Develop lists of local volunteers who can contact vulnerable neighbors. Provide them companionship. Help them order food and medications. Recruit teenagers and college students to teach digital communications skills to older people with distant relatives and to deliver groceries to those too weak or anxious to shop. Call the nearest homeless shelter or food pantry and ask if it needs anything.

Why not begin right now?’

‘If you’re like me and worried about your favorite local businesses right now, buy their gift certificates. It will help with their immediate liquidity needs and you can use it later once we’re past this.’

CANTICLE 6

by May Sarton

Alone one is never lonely: the spirit

adventures, waking

In a quiet garden, in a cool house, abiding single there;

The spirit adventures in sleep, the sweet thirst-slaking

When only the moon’s reflection touches the wild hair.

There is no place more intimate than the spirit alone:

It finds a lovely certainty in the evening and the morning.

It is only where two have come together bone against bone

That those alonenesses take place, when, without warning

The sky opens over their heads to an infinite hole in space;

It is only turning at night to a lover that one learns

He is set apart like a star forever and that sleeping face

(For whom the heart has cried, for whom the frail hand burns)

Is swung out in the night alone, so luminous and still,

The waking spirit attends, the loving spirit gazes

Without communion, without touch, and comes to know at last

Out of a silence only and never when the body blazes

That love is present, that always burns alone, however steadfast.

Last night I watched a documentary on war,

and the part I carry with me today

was the spectacle of a line

of maybe 20 blinded soldiers

being led, single-file,

away from a yellow cloud of gas.

That must be what accounts

for this morning’s brightness—

sunlight slathered over everything

from the royal palms to the store awnings,

from the blue Corolla at the curb

to a purple flower climbing a fence,

one gift of sight after another.

I couldn’t see their bandaged faces,

but each man had one hand

resting on the shoulder

of the man in front of him

so that every man was guiding

and being guided at the same time,

and in the same tempo,

given the unison of their small, cautious steps.

~Billy Collins

Fire activity picked up across the United States this week. 45 new large fires were reported most of them in Oklahoma. Get more information a

Dorothy & Rebecca

March 9, 2020Dorothy Day [1997-1980], journalist and social activist, was 8 years old on the night of April 18th, 1906, living in Oakland, during the San Francisco earthquake.

‘There were broken dishes all over the floor, along with books, chandeliers, and pieces of the ceiling and chimney. The city was in ruins, too, temporarily reduced to poverty and need. But in the days after, Bay Area residents pulled together. “While the crisis lasted, people loved each other,” she wrote in her memoir decades later. “It was as though they were united in [compassionate] solidarity. It makes one think of how people could, if they would, care for each other in times of stress, unjudgingly in pity and love” [David Brooks, The Road to Character, 2015, pp. 74-75.].’

‘Writer and editor Paul Elie has said, “A whole life is prefigured in that episode”…the crisis, the tense of God’s nearness, the awareness of poverty, the feeling of loneliness and abandonment, but also the sense that that loneliness can be filled by love and community, especially through solidarity with those in the deepest need [Brooks, p. 75].’

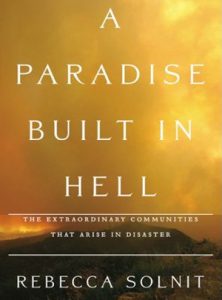

The most startling thing about disasters, according to award-winning author Rebecca Solnit, is not merely that so many people rise to the occasion, but that they do so with joy. That joy reveals an ordinarily unmet yearning for community, purposefulness, and meaningful work that disaster often provides.

A Paradise Built in Hell is an investigation of the moments of altruism, resourcefulness, and generosity that arise amid disaster’s grief and disruption and considers their implications for everyday life. It points to a new vision of what society could become-one that is less authoritarian and fearful, more collaborative and local.

NYTimes:

“What is this feeling that crops up during so many disasters?” Ms. Solnit asks. She describes it as “an emotion graver than happiness but deeply positive,” worth studying because it provides “an extraordinary window into social desire and possibility.” Our response to disaster gives us nothing less than “a glimpse of who else we ourselves may be and what else our society could become.” Her overarching thesis can probably be boiled down to this sentence: “The recovery of this purpose and closeness without crisis or pressure” without disaster, that is “is the great contemporary task of being human.”

In “A Paradise Built in Hell” Ms. Solnit probes five disasters in depth: the 1906 earthquake and fires in San Francisco, the Halifax munitions cargo ship explosion of 1917, the Mexico City earthquake of 1985, the events of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina. She also writes about the London blitz, Chernobyl and many other upheavals and examines the growing field of disaster studies [2009].

Compassion, love and truth.

February 22, 2020

‘Human nature is not evil. All pleasure is not wrong. All spontaneous desires not selfish. The doctrine of original sin does not mean that human nature has been completely corrupted and that man’s freedom is always inclined to sin.

Man is neither a devil nor an angel. He is not pure spirit, but a being of flesh and spirit, subject to error and malice, but basically inclined to seek truth and goodness. He is, indeed, a sinner: but their hearts respond to love and grace. It also responds to the goodness and to the need of his fellowman.’

-Thomas Merton, Life and Holiness [1963]

If we over-use the intellectual center, then our work lies in bringing the emotional and moving centers fully online and integrating them. Wisdom is a way of knowing that goes beyond one’s mind, one’s rational understanding, and embraces the whole of a person: mind, heart, and body. These three centers must all be working, and working in harmony, as the first prerequisite to the Wisdom way of knowing.

—Cynthia Bourgeault

This essay is excerpted from W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon droop and the last tide fail,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail,

As the water all night long is crying to me.

— Arthur Symons

“Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the years all this fine contempt began to fade; for the worlds I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head,—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian,

the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten.

The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to lose effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness,—it is the contradiction of double aims. The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand to escape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart in either cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister or doctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of another people. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of ten thousand thousand people,—has sent them often wooing false gods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faith as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to a promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came,—suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood and passion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

“Shout, O children!

Shout, you’re free!

For God has bought your liberty!”

Years have passed away since then,—ten, twenty, forty; forty years of national life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthy spectre sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation’s feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastest social problem:—

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!”The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people,—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp,—like a tantalizing will-o’-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host.

The holocaust of war, the terrors of the Ku-Klux Klan, the lies of carpet-baggers, the disorganization of industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he now regarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which war had partially endowed him.

And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal to vote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dream of political power,—a powerful movement, the rise of another ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after a clouded day. It was the ideal of “book-learning”; the curiosity, born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway of Emancipation and law, steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here and there a foot had slipped or some one had fallen. To the tired climbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting-place, little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In those sombre forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself,—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully count his bastards and his prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling, sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Men call the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the natural defence of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance, purity against crime, the “higher” against the “lower” races. To which the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to so much of this strange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization, culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meekly does obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leaps beyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nigh speechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, the ridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact and wanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and the boisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to the devil,—before this there rises a sickening despair that would disarm and discourage any nation save that black host to whom “discouragement” is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came borne upon the four winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the black man’s ballot, by force or fraud,—and behold the suicide of a race! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something of good,—the more careful adjustment of education to real life, the clearer perception of the Negroes’ social responsibilities, and the sobering realization of the meaning of progress.

So dawned the time of Sturm und Drang: storm and stress to-day rocks our little boat on the mad waters of the world-sea; there is within and without the sound of conflict, the burning of body and rending of soul; inspiration strives with doubt, and faith with vain questionings. The bright ideals of the past,—physical freedom, political power, the training of brains and the training of hands,—all these in turn have waxed and waned, until even the last grows dim and overcast. Are they all wrong,—all false? No, not that, but each alone was over-simple and incomplete,—the dreams of a credulous race-childhood, or the fond imaginings of the other world which does not know and does not want to know our power. To be really true, all these ideals must be melted and welded into one. The training of the schools we need to-day more than ever,—the training of deft hands, quick eyes and ears, and above all the broader, deeper, higher culture of gifted minds and pure hearts. The power of the ballot we need in sheer self-defence,—else what shall save us from a second slavery? Freedom, too, the long-sought, we still seek,—the freedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, the freedom to love and aspire.

Work, culture, liberty,—all these we need, not singly but together, not successively but together, each growing and aiding each, and all striving toward that vaster ideal that swims before the Negro people, the ideal of human brotherhood, gained through the unifying ideal of Race; the ideal of fostering and developing the traits and talents of the Negro, not in opposition to or contempt for other races, but rather in large conformity to the greater ideals of the American Republic, in order that some day on American soil two world-races may give each to each those characteristics both so sadly lack.

We the darker ones come even now not altogether empty-handed: there are to-day no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes; there is no true American music but the wild sweet melodies of the Negro slave; the American fairy tales and folk-lore are Indian and African; and, all in all, we black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in a dusty desert of dollars and smartness. Will America be poorer if she replace her brutal dyspeptic blundering with light-hearted but determined Negro humility? or her coarse and cruel wit with loving jovial good-humor? or her vulgar music with the soul of the Sorrow Songs?

Merely a concrete test of the underlying principles of the great republic is the Negro Problem, and the spiritual striving of the freedmen’s sons is the travail of souls whose burden is almost beyond the measure of their strength, but who bear it in the name of an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers’ fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.

And now what I have briefly sketched in large outline let me on coming pages tell again in many ways, with loving emphasis and deeper detail, that men may listen to the striving in the souls of black folk.”

As Rebecca Solnit explains, hope is “coming to terms with the fact that we don’t know what will happen and that there’s maybe room for us to intervene, and that we have to let go of the certainty people seem to love more than hope and know that we don’t know what’s going to happen.” To practice hope as Solnit describes it requires acknowledging a similar incompleteness to the one that Consolmagno speaks about.

Perhaps embracing the inherent incompleteness of what we know of the world is a form of hope, allowing us to remember that there’s always something left to unfold or be discovered — and not always in the way we might’ve been conditioned to expect it. May we allow ourselves to listen, and even delight in its surprises, as we work alongside the richness of this incompleteness.

Fr. Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation:

‘The good, the true, and the beautiful are their own best argument for themselves, by themselves, and in themselves. Such deep inner knowing evokes the soul and pulls the soul into All Oneness. Incarnation is beauty, and beauty needs to be incarnate—that is specific, concrete, particular. We need to experience very particular, soul-evoking goodness in order to be shaken into what many call “realization.” It is often a momentary shock where we know we have been moved to a different plane of awareness.’

H O P E

January 2, 2018‘Hope for me is deeply tied to the fact that we don’t know what will happen. This gives us grounds to act.’

“On January 18th, 1915, six months into the first world war, as all Europe was convulsed by killing and dying, Virginia Woolf wrote in her journal, ‘The future is dark, which is on the whole, the best thing the future can be, I think.’ Dark, she seems to say, as in inscrutable, not as in terrible. We often mistake the one for the other. Or we transform the future’s unknowability into something certain, the fulfillment of all our dread, the place beyond which there is no way forward. But again and again, far stranger things happen than the end of the world.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to read you a note from a father to his three daughters on election night, after the kids had pledged a compact to invest their next four years in looking inwards towards the family and relationships and the things that mattered to them the most. The note went as follows:

“Yes, we must look inwards and cherish one another, holding onto our precious love where our own values seem so under attack. But please, we must not retreat from the world, we must never stop believing in and fighting for what is just and sane. Loathe as I am to be a backseat driver in your lives, I do implore you, be courageous. Live your life fighting the fight.”

I’m intimately familiar with those sentiments because I wrote them, but notwithstanding my encouragement to my daughters, no matter what the scope of history one day will provide, in the foreseeable future we are likely as a society to go abruptly and maybe irretrievably backwards on civil rights, human rights, climate, sanity.

REBECCA SOLNIT: You’re talking about two different things, how do we feel and what do we do. And I’m not telling people how to feel, I’m telling people that there is scope for action. One of the great conundrums is that unless we believe there are possibilities we don’t act, but the possibilities only exist if we seize them. And so, a lot of what I’ve been trying to do is encourage people to recognize there is an extraordinary history of popular power in the US but also around the world. I’m not an optimist, as you said in your introduction. Optimism believes that everything will be fine, no matter what we do and, therefore, we don’t have to do a damn thing. Pessimism is the mirror image of that – that believes that everything’s going to hell in a hand basket, and it gets us off the hook. We don’t have to do anything.

Hope for me is deeply tied to the fact that we don’t know what will happen. This gives us grounds to act. And the Trump administration is such an amplifier of uncertainty. Will the guy have some kind of breakdown? Will he get impeached? Will he start World War IV? Will the Republican Party split? Will the Democratic Party find its backbone? So I think that there’s grounds to stay engaged, while being clear that terrible things are happening and we should mourn them.

You keep wanting to talk about despair and I’m just not very interested in it. The situation on climate, which I spent a lot of time looking at and trying to do something about as an activist, is really bleak but there’s wiggle room in there. You know, a lot of extraordinary stuff is happening and it’s happening in very complex ways. One thing that not very many people have noticed, because it’s a change so incremental, is that the technology of renewable non-carbon energy has evolved so dramatically over the last dozen years that we’re in a completely different place than we were at the beginning of the millennium. Bloomberg News ran a story yesterday that within the decade solar power is likely to be cheaper than coal, which is the cheapest fossil fuel. We actually have the energy solutions and they are being adapted pretty rapidly in a lot of places.

You know, we also are looking at the Antarctic ice shelf cracking. We’re looking at sea level rise. We’re looking at chaotic weather. We’re in a very deep crisis. You know, and I want people to be able to hold both of those things. We’re not talking about a future that’s already written.

What we get from the mainstream media over and over and over is a story that what we do doesn’t matter. We have had huge impacts. We have changed what constitutes what’s acceptable and ordinary in innumerable ways. You can tell the story of same-sex marriages, oh, the Supreme Court in its beneficence handed this nice thing down to us, but the Supreme Court decided that this was normal because millions of people had transformed our society in powerful ways over decades about what was normal, and so they did what seemed reasonable, but we defined what reasonable is.

The future is not yet written. What the story is depends on what we make it, and that’s really what I’m here to say.”

Rebecca Solnit is a writer, historian and activist. She’s the author of Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities.

[Full Interview on WNYC/On The Media: https://www.wnyc.org/story/otm-rebecca-solnit-hope-lies-and-making-change/]

[Photo: Prayer Wheel in Sun Valley, Idaho]

‘May the frightened cease to be afraid and those bound be freed; may the powerless find power, and may people think of benefitting one another.’ Shantideva

Hope.

July 3, 2016Victor Frankl:

‘Without hope there is no meaning. Without meaning there is no hope.’

~

Elie Wiesel:

‘For me, hope without memory is like memory without hope.’

~

Maria Papova:

Critical thinking without hope is cynicism. Cynicism without critical thinking is naïveté.

~

Rebecca Solnit

The moment passed long ago, but despair, defeatism, cynicism, and the amnesia and assumptions from which they often arise have not dispersed, even as the most wildly, unimaginably magnificent things came to pass. There is a lot of evidence for the defense… Progressive, populist, and grassroots constituencies have had many victories. Popular power has continued to be a profound force for change. And the changes we’ve undergone, both wonderful and terrible, are astonishing.

[…]

This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen. It’s also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both.

[…]

There’s a public equivalent to private depression, a sense that the nation or the society rather than the individual is stuck. Things don’t always change for the better, but they change, and we can play a role in that change if we act. Which is where hope comes in, and memory, the collective memory we call history.

[…]

You row forward looking back, and telling this history is part of helping people navigate toward the future. We need a litany, a rosary, a sutra, a mantra, a war chant for our victories. The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future.

‘…faith, while change moves slowly along.’

March 11, 2016‘Rebecca Solnit Explains Things to Us…’

There’s this idea that political engagement is some sort of horrible, dutiful thing you do, like cleaning the toilet or taking out the garbage. But it can be the most fantastic thing you do. It can bring you into contact with hope, with joy, with a sense of deep connection, with what Martin Luther King called the “beloved community.” Disconnection from a larger sense of purpose and agency, from community and civil society, and from hope are huge factors in unhappiness.

Hating on people has never been a great form of social change, so far as we know.

I have preferences and they’re probably not that hard to guess. But with Obama, people so completely put their faith in: “Oh, we’ll elect this magic, amazing super-human and then we’ll all go home and do absolutely nothing.” The movement that put Obama in office was powerful enough to make really profound change, but everyone went home because they thought he’d do it.

That’s what you see with Bernie Sanders: this infatuation with an almost savior-like figure who will do it all. No, actually, massive grassroots movements need to exist the day after the election. Electoral politics are dismal; I’m more interested in grassroots power, popular power.

[This post originally appeared at In These Times.]

In a dispatch from Paris for Harper’s, writer and activist Rebecca Solnit called the recent climate agreement negotiated there “miraculous and horrible.” This tension between the exciting and the awful, the transformative and the terrifying, motivates her book Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. Initially written in response to the Iraq War, the book will be re-released this month with a new section on climate change.

Bill Moyers

http://billmoyers.com/story/rebecca-solnit-explains-things-to-us/