Questions

On Being

December 8, 2019The Pause

Loving the Questions

In 1974, a 15-year-old Serene Jones sat at a campfire sing-along that helped shape her understanding of America and its complicated relationship to its own story. She and her fellow campers were singing along to the familiar lyrics of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” when she learned for the first time that the song actually has a few lesser-known verses, including:

“In the shadow of the steeple I saw my people,

By the relief office I seen my people;

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?”

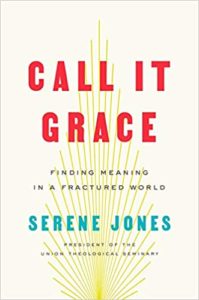

She writes in her book Call it Grace bout how hearing these more critical lyrics to a popular American song was a moment of revelation. Even decades later, she’s held onto the memory as a metaphor for America’s tendency to shine light on the “sunny, hopeful, and helpful” while “[lopping] off the uncomfortable verses about our lives.”

And in this week’s On Being, Jones talks about how her work as a public theologian is about reconciling these two realities in humanity: Both our propensity for love and connection, as well as our capacity for hatred and cruelty. She says it’s the work of connecting our personal stories to this bigger question — what does it mean to be human? — that makes theology such an important exercise. “What is theology, if it’s not talking about our collective lives and the meaning and purpose of our lives and how we’re supposed to live together and who God is, in ways that are part of our conversation together?”

Serene Jones describes theology as the place and story you think of when you ask yourself about the meaning of your life, the world, and the possibility of God. For her, that place is a “dusty piece of land” on the plains of Oklahoma where she grew up. “I go there to find my story — my theology. I go there to be born again; to be made whole; to unite with what I was, what I am, and what I will become.” In her work as a public theologian, Jones explores theology as clarifying lens on the present — from grace to repentance to the importance of moving from grieving to mourning.

Rilke:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue,” he wrote. “Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”