Moon Trees

Moon Trees 🌕

February 2, 2022We Almost Forgot About the Moon Trees

A collection of tree seeds that went round and round the moon was scattered far and wide back home.

By Marina Koren

Apollo 14—the third of six moon landings—is known, as I recently discovered, for its “moon trees.”

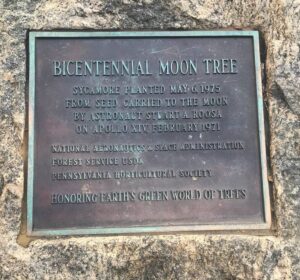

Stuart Roosa, one of the Apollo 14 astronauts, took a small canvas bag of tree seeds with him on the journey. While his fellow astronauts walked on the lunar surface, Roosa and the seeds flew round and round the moon until the crew was ready to come back. A few years after the astronauts returned home, some of the seeds—sycamores, redwoods, pines, firs, and sweetgums—were planted across the United States, to see how they would grow, or simply to keep a piece of moon history close by.

That I could find a database of these trees, and go through the experience of identifying and losing the moon tree nearest me in five seconds, is because of Dave Williams, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who 25 years ago took it upon himself to locate as many of them as he could. NASA didn’t keep any records on where the seeds from Apollo 14 ended up, nor did the agency keep up with the trees they became. But Williams does, even though it’s not part of his job description. He is not a tree expert, but he has become, through his efforts, the world’s foremost—and perhaps only—expert on moon trees.

(It was) discovered that the head of the U.S. Forest Service had pitched Roosa, a former smoke jumper who fought forest fires, on the idea. The astronaut took about 500 seeds stuffed in sealed bags inside a metal canister, packed in the small canvas bag that every Apollo astronaut was allowed to fill with whatever they wanted. When the astronauts came back, the sealed bags went through a vacuum chamber—part of the standard decontamination protocol at the time—and accidentally burst, scattering the seeds. Stan Krugman, a geneticist at the forest service, sorted them by hand, then passed them on to a scientist who used some to experiment with germination at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, in Houston. The rest were sent to forestry-science facilities, which doled them out to communities across the country, grateful for a free piece of the Apollo era to spice up their municipal grounds.

The trees, planted mostly in 1976, took root just fine on Earth. Some of the moon seeds were planted next to seeds that had never traveled to space, to see whether they’d develop any differently. The most surprising result, Williams told me, occurred when the two seeds grew into two completely different species—a result of a gardening mixup, of course, not the weird effects of microgravity. NASA didn’t undertake any serious study of the moon trees. The effort was more a PR move, Williams said, than a science experiment.

All the trinkets and tchotchkes that the Apollo astronauts took with them in their personal canvas bags are cool for this reason, bestowed with a magical sheen the second they were returned to Earth—space souvenirs. But the seeds that Roosa, who died in 1994, carried feel different from other mementos. They weren’t put in museums or auctioned off. They were buried in the soil of the Earth, the only soil like it in the solar system—in the entire universe, as far as we know. Some might have disappeared, felled by storms or saws, before someone could find them and feel curious enough to ask NASA about them. But the ones that remain are living monuments to the time humankind escaped this world’s gravity and felt that of another.’

From nasa.gov: