Media

Hyperobjects and the challenges ahead. #MustRead

July 8, 2021I wrote a long essay about a pervasive feeling I have about the future. I do not think we are ready for the complex, existential challenges ahead. -Charlie Warzel

We are not ready.

On the climate crisis and other hyperobjects.

These days, I find increasingly myself caught between the worry that I’m being overly alarmist and the fear that I am stating the obvious.

I felt this most strongly in October 2020. Covid cases were surging; the presidential election was near; the far-right areas of the internet I kept an eye on were vibrating with a dark potential energy. All summer, I watched anxiously as people posted videos online of furious Americans taking to the streets. I listened in on walkie-talkie apps as so-called militia groups attempted to recruit and deploy members. News reports said sales of guns and ammo were surging.

I was seized by a deep, persistent dread that these anecdotal instances of civil conflict were a prelude to something bigger. I interviewed scholars who’ve studied revolutions and shared my fears.

Sept. 30th, 2020:

“Reading this exchange…it’s honestly very surprising to me the extent to which we haven’t seen more Kenosha like events already…”

I struggled — and ultimately failed — to put any of this into words at the time. I didn’t know how to convey these anecdotal stories into something that went beyond projecting my anxieties onto the world via the pages of the New York Times. I felt I lacked the language to proportionally describe my concern. I was legitimately worried about large-scale, sustained violent civil conflict across the United States but, if I’m being honest, I was afraid I’d come off as the extremely online, overly alarmist guy.

And yet, if you did occupy the same spaces as I did in October 2020, the specter of civil conflict would have felt just so incredibly obvious as to almost not be worth mentioning. The world was shut down, everyone was trapped inside and online, and more and more people were beginning to detach from reality. Everyone was miserable and scared and angry. Just look around!

This moment offers a window into the way that traditional conceptions and practices of journalism can break down in extraordinary times. I consider not writing this piece back in October a failure. I wrote plenty of columns around and tangential to this subject, yes. But my job is to look at the world through the lens of information and technology and to describe how those elements shape our culture and our politics. I saw something and I didn’t say all of what I thought, in part, because I couldn’t figure out how to talk about it proportionally. I was also pretty fucking scared: of being wrong, but also of being right.

Was I wrong or right? …Yes? There has not been a series of extended, mass casualty conflicts so far — no Civil War 2. But I also urge you watch this video reconstructing January 6th in full and tell me that my sleepless nights in October were a gross overreaction.

Even now, I struggle to find the adequate word to describe the moment. It makes sense: our 21st century existence is characterized by the repeated confrontation with sprawling, complex, even existential problems without straightforward or easily achievable solutions.

Theorist Timothy Morton calls the larger issues undergirding these problems “hyperobjects,” a concept so all-encompassing that it resists specific description. You could make a case that the current state of political polarization and our reality crisis falls into this category. Same for democratic backsliding and the concurrent rise of authoritarian regimes. We understand the contours of the problem, can even articulate and tweet frantically about them, yet we constantly underestimate the likelihood of their consequences. It feels unthinkable that, say, the American political system as we’ve known it will actually crumble.

Climate change is a perfect example of a hyperobject. The change in degrees of warming feels so small and yet the scale of the destruction is so massive that it’s difficult to comprehend in full. Cause and effect is simple and clear at the macro level: the planet is warming, and weather gets more unpredictable. But on the micro level of weather patterns and events and social/political upheaval, individual cause and effect can feel a bit slippery. If you are a news reporter (as opposed to a meteorologist or scientist) the peer reviewed climate science might feel impenetrable. It’s easiest to adopt a cover-your-ass position of: It’s probably climate change but I don’t know if this particular weather event is climate change.

Hyperobjects scramble all our brains, especially journalists. Journalists don’t want to be wrong. They want to react proportionally to current events and to realistically frame future ones. Too often, these desires mean that they do not explicitly say what their reporting suggest. They just insinuate it. But insinuation is not always legible.

I understand these fears and I feel them myself, professionally and personally. I think anyone who says they don’t feel them is probably lying. In fact, these fears, in the right proportion, make for what we traditionally consider a “good journalist.”

After all, many of the best journalists understand how to balance and factor uncertainty into their work. I don’t want journalists to jump to lazy conclusions. I think a deeper embrace of nuance and uncertainty is necessary not just in reporting, but in all elements of mass media.

That embrace sounds good in theory but it’s much harder in practice. How do you talk about an impending, probable-but-not-certain emergency the *right way*? Can you even do that? Can you get people ready for an uncertain, perhaps unspeakably grim future? Is anyone ready?

These questions have re-entered my brain again as I’ve scrolled the news the last few weeks. In late May and early June, there were a rash of reports about Republican efforts to restrict voting rights and halt Democrats’ expansion efforts. There was lots of warranted handwringing about the ways that Republican state legislatures are poised to consolidate power at the local level that could threaten the legitimacy of future presidential elections. Congress was unable to agree to even investigate January 6th, prompting the New Yorker to run the headline, “American Democracy Isn’t Dead Yet, but It’s Getting There.”

The overwhelming message of these pieces was that the America was running out of time on its claim of having even a remotely functioning political system. Even more worrying was the tone, which seemed to suggest it might not feel bad right now, but it’s far worse than you think. “My current level of concern is exploring countries to move to after 2024,” one political scientist told Vox in late May. Cool, cool. My personal doom indicator was a Reuters/Ipsos poll from May, as in two months ago, which found that 53% of Republicans believe Trump is the “true president.”

There are so many dire elements in the forecast for our political future. It seems like a truly formidable challenge for a country to overcome.

Which is why one piece of reporting from this past month felt like a true gut punch. In the Times, Ben Smith wrote a media column about Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, who remains a prolific source for political reporters in Washington, D.C. “Mr. Carlson’s comfortable place inside Washington media, many of the reporters who cover him say, has taken the edge off some of the coverage. It has also served as a kind of insurance policy, they say, protecting him from the marginalization that ended the Fox career of his predecessor, Glenn Beck,” Smith wrote. “‘If you open yourself up as a resource to mainstream media reporters, you don’t even have to ask them to go soft on you,’” a journalist told Smith in the piece.

I’ve reported on the far-right. I understand that the reporting process frequently brings you into contact with loathsome individuals and that, at times, these people can be quite helpful, because cynical political grifters love to turn on each other and gossip and vent just like everyone else. I’ve broken some stories, stories I’m proud of, off tips from true cretins — so take my pearl clutching with whatever grains of salt you wish.

Still, Smith’s column haunted me. You can argue Carlson is who he has always been, or that his Trump era project of (barely) laundering white nationalist talking points into mainstream political discourse is disingenuous, pandering to viewers for whom he has utter contempt. I don’t care. What I do care about is a political press that has a seemingly neutral or symbiotic relationship with a guy who beams this rhetoric into three million homes a night:

[Tucker Carlson soundbite; will not post. -dayle]

It’s worth noting that some of those same articles I read back in the fall, warning of democratic backsliding, single out Carlson as one of the animators of a dark grievance culture that threatens our social/political fabric. “The strongest factors are racial animosity, fear of becoming a white minority and the growth of white identity,” Virginia Gray, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina told the Times’ Tom Edsall, singling out a Carlson monologue from April.

It’s hard for me to square the Carlson source coziness with the host’s increasingly dangerous replacement theory and anti-vaxx rhetoric. The disconnect between the threat Carlson poses and the political media’s shrugging proximity to him fills me with a deep dread for my industry — and a very real concern that it will not be able to rise to the challenge of our moment (a shaky democratic foundation, increasingly fewer points of shared reality, a climate emergency, to name a few).

I’m not trying to dog reporters working in a shitty, gutted media ecosystem that mostly runs off algorithmic attention and online advertising that most people hate. There is no shortage of vital, journalism going on. But, structurally, there are still glaring problems with some traditional outdated journalistic norms and practices: management that still struggles to understand complex internet dynamics, a commitment to journalistic impartiality that does not work in an era where one political party has largely abandoned democracy and, in some cases, reality.

Over the last half decade, I watched political journalists and editors tie themselves in knots arguing over whether to call Trump a racist or whether the Republican party was really becoming anti-democratic or whether Trump’s election denial was a “coup.” In each instance there’s a side arguing that the other needs to calm down, that things are not as bad as they appear. I used to think these people had a lack of imagination.

Now, I see it as a strong normalcy bias. Writer Jonathan Katz calls this an ‘unthinkability’ that “pervades conversations about so many things in our moment.” Basically: we humans are good at repressing terrifying realities that feel unthinkable and steering them back into more acceptable bounds of conversation.

Climate coverage offers the clearest picture of this ‘unthinkability’ dynamic. In a clip from June 7th, CBS meteorologist Jeff Berardelli describes a heat wave stifling the east coast and the exceptional levels of draught in the West. His tone is urgent and the maps he’s gesturing to on the screen are alarming. He doesn’t mince words. “This is a climate emergency,” he tells one of the morning show anchors. It’s the kind of grim statement that you might imagine would evoke a bit of stunned silence.

Instead, the anchor smiles broadly and shakes his head in faux disbelief. “It’s very hot! I feel parched just talking about it!” he says in perfect, playful news cadence. Berardelli and the others on set offer up a classic morning show chuckle. Isn’t that something else! Banter! Onto the next segment.

[CBS warning of extreme heat soundbite.]

This is a particularly egregious example of a conventional form of media (in this case, the lighthearted morning show segment) that is woefully inadequate for the subject matter (the existential heating of the planet that will render large swaths of it hostile to human life in the near future).

In her excellent newsletter Heated, Emily Atkin has written about the systemic failureof the media to inform readers/viewers as to why it is so goddamn hot this summer. She cites the work of Colorado journalist Chase Woodruff, who surveyed recent reporting on the state’s recent heat wave and found that out of “149 local news stories written about the unprecedented hot temperatures…only 6 of those stories mentioned climate change.” The others, Atkin notes, “covered it as if it were an act of God.”

This behavior isn’t new. Back in 2018, Atkin wrote a story on the media’s failure to connect the dots on climate change. NPR’s science editor told her that “You don’t just want to be throwing around, ‘This is due to climate change, that is due to climate change.’” The editor required reporters to speak to a climate scientist before being allowed to attribute extreme temperatures to climate change. It’s an instance, Atkin argues, of “over-abundance of journalistic caution” — primarily attributable to fear. Fear of backlash from denialists, politicians, or other journalists — maybe even fear of being right.

In my mind, there’s an incredibly important distinction between embracing complexity and uncertainty in the world and what those Colorado publications, following the lead of so many others, did by not mentioning climate change — because, well, weather is complex and we don’t want to get yelled at so who’s to say?!! The problem isn’t legitimate nuance. It’s when decision makers in the media space use the existence of uncertainty as an excuse not to say what needs to be said.

Sometimes, though, mistakes aren’t nefarious. A missed or botched narrative is caused by a little bit of everything. A lot of the retroactive criticism around coronavirus coverage pre-March 2020 was that big media outlets downplayed pandemic fears because they relied heavily on credible expert sources who themselves were inclined not to be alarmists. Some in the media were doing their job just as intended and unwittingly providing false comfort. Others were providing false comfort because they didn’t want to be outliers. And another group mostly ignored the threat because platform or other media incentives directed their focus away from an unknown respiratory illness in China.

These scenarios are the product of living with and reporting on hyperobjects. The big picture — we’re losing our grip on what’s real; our political system is fraying and unsustainable; the planet is burning — is pretty clear and obvious. But many of the particulars (Is that specific hurricane climate change? Is this bill/piece of misinformation/person a threat to the democracy?) become skirmishes in the culture war.

I don’t particularly know what to do about any of this. One problem when facing down a hyperobject-sized crisis is that it overwhelms. In a recent piece, Sarah Miller articulated what it feels like to stare down existential dread on the subject of climate change. She argues that, after a certain point, traditional methods, like writing, feel futile:

“Let’s give the article…the absolute biggest benefit of the doubt and imagine that people read it and said, “Wow this is exactly how I feel, thanks for putting it into words.” What then? What would happen then? Would people be “more aware” about climate change? It’s 109 degrees in Portland right now. It’s been over 130 degrees in Baghdad several times. What kind of awareness quotient are we looking for? What more about climate change does anyone need to know? What else is there to say?

Miller’s questions ask us to consider and reconsider what our roles are right now. Yes, we have our jobs and the way we’ve been trained or conditioned or rewarded to do them and that’s all very fine and good. But what about now? Does that training hold up in remarkable, existential-feeling moments like the one we are in? Are these jobs, the way we’ve been taught to do them, important now? How do we prepare people for the uncertain, grim contours of the future? Can we do that?

I think these are the questions journalists have to be asking ourselves at every moment right now. But not just journalists. Hyperobject-sized problems impact everyone. That’s why they’re hyperobjects. And I don’t think any of us are ready. The pandemic showed us how difficult it is, at a societal level, to grasp complex ideas like, say exponential growth. And there are examples everywhere of our human inability to think longterm or pay big costs upfront to avoid catastrophe later (See: this haunting interview about the Miami condo collapse).

But not being ready isn’t quite the same as being doomed to a foregone conclusion. There’s the way we’ve done things and the way we need to do things now. How do we make up the difference between those two notions? We must be probabalistic in our predictions and understanding when they fall short. We need all need to learn to work and think on different levels, holding steadfastly to what is not up for debate, and not dividing ourselves needlessly over what is.

As good as that might sound, I feel foolish writing it. I’m not all that certain any human being can hold such conflicting notions in their head all the time. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth trying.

Living with hyperobjects is hard. I don’t think we’re ready for any of what is to come. I feel alarmist saying this. But it also feels incredibly obvious.

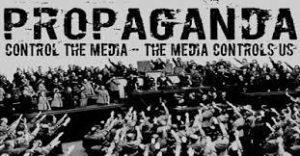

The media is complicit.

June 5, 2021As an institution, the media no longer reflects, it shapes. NYTimes columnist Ezra Klein recently spoke with President Barack Obama about how the United States transitioned from “Yes We Can to MAGA.” Thoughtful questions and deeply reflective answers. Here I extrapolate President Obama’s comments about the media and his worried concerns about how the narrative is shaped through social media and far-right ‘news’ sources. -dayle

Full interview:

“What you just identified, in part because of the media infrastructure I described, and the siloing of media, in part because of, then, the Trump presidency and the way both sides went to their respective fortresses, absolutely. I think it’s real. I think it’s worse.

The decline of other mediating institutions that provided us a sense of place and who we are, whether it was the church, or union, or neighborhood, those used to be part of a multiple set of building blocks to how we thought about ourselves.

It spills over into everyday life and even small issues, what previously were not considered even political issues.

But some of it is a media infrastructure that persuaded a large portion of that base that they had something to fear and fed on that fear and resentment, that politics of fear resentment, in a way that, ironically, ended up being a straitjacket for the Republican officials themselves. And some of them got gobbled up by the monster that had been created and suddenly found themselves retiring. And they couldn’t function, because they weren’t angry or resentful enough for the base they had stoked.

It taught somebody like a Mitch McConnell that there is no downside for misstating facts, making stuff up, engaging in out and out obstruction, reversing positions that you held just a few minutes ago. Because now, it’s politically expedient to do so. That never reached the public in a way where the public could make a judgment about who’s acting responsibly and who isn’t.

And that, I think, was not driven by the politics of the moment. I mean, I think that the media was complicit in creating that dynamic in a way that is difficult. Because as we discovered during the Trump administration, if an administration is just misstating facts all the time, it starts looking like, gosh, the media’s anti-Trump. And this becomes more evidence of a left wing conspiracy, and liberal elites trying to gang up on the guy.

Ezra: I will say, in the media, one of our central biases is towards exciting candidates. You were an exciting candidate in 2008, but later on, that’s also something that Donald Trump activates.

President Obama: In a different way. You have a big set piece at the White House Correspondents Dinner, where “The Washington Post” invites Donald Trump after a year of birtherism to sit at their table.

But even in a broader sense, exciting candidates are usually, one, they shape perceptions of parties. But two, on the right, they tend to be quite extreme. They definitely tend to be in both directions, either more liberal or more conservative. But part of the dynamic, I think, you’re talking about — and then the media is pressured by social media, where —

You look out there, and you look around, like who’s up there on Facebook and on Reddit. And conflict sells.

But I have to tell you that there’s a difference between the issue of excitement, charisma, versus rewarding people for saying the most outrageous things.

So I don’t agree that that’s the only way that you can get people to read newspapers or click on a site. It requires more imagination and maybe more effort. And it requires some restraint to not feed the outrage, inflammatory approach to politics. And I think that folks didn’t do it.

And look, as I note towards the end of the book, the birther thing, which was just a taste of things to come, started in the right wing media ecosystem. But a whole bunch of mainstream folks, who later got very exercised about Donald Trump, they booked him all the time. Because he boosted ratings. But that wasn’t something that was compelled.

It was convenient for them to do. Because it was a lot easier to book Donald Trump to let him claim that I wasn’t born in this country than it was to how do I actually create an interesting story that people will want to watch about income inequality. That’s a harder thing to come up with.

My entire politics is premised on the fact that we are these tiny organisms on this little speck floating in the middle of space. The analogy I always used to use when we were going through tough political times, and I’d try to cheer my staff up, then I’d tell them a statistic that John Holdren, my science advisor, told me, which was that there are more stars in the known universe than there are grains of sand on the planet Earth.

I guess, that my politics has always been premised on the notion that the differences we have on this planet are real. They’re profound, and they cause enormous tragedy as well as joy. But we’re just a bunch of humans with doubts and confusion

We do the best we can. And the best thing we can do is treat each other better, because we’re all we got. And I would hope that the knowledge that there were aliens out there would solidify people’s sense that what we have in common is a little more important.

Three books, a book I just read, “The Overstory” by Richard Powers, it’s about trees and the relationship of humans to trees. And it’s not something I would have immediately thought of, but a friend gave it to me. And I started reading it, and it changed how I thought about the earth. And it changed how I see things, and that’s always, for me, a mark of a book worth reading.

“Memorial Drive” by Natasha Trethewey, it’s a memoir, just a tragic story. Her mother’s former husband, or her former stepfather, murders her mother. And it’s a meditation on race, and class, and grief, uplifting surprisingly, at the end of it but just wrenching.

And then this one is easier to remember. I actually caught up on some past readings of Mark Twain. There’s something about Twain that I wanted to revisit, because he speaks a little bit of — he’s that most essential of American writers. And there’s his satiric eye and his actual outrage that sometimes gets buried under the comedy I thought was useful to revisit.”

Mark Twain considered his best book to be one he spent 12 years writing. Excellent.

-dayle

Amazon:

Very few people know that Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) wrote a major work on Joan of Arc. Still fewer know that he considered it not only his most important but also his best work. He spent twelve years in research and many months in France doing archival work and then made several attempts until he felt he finally had the story he wanted to tell. He reached his conclusion about Joan’s unique place in history only after studying in detail accounts written by both sides, the French and the English. Because of Mark Twain’s antipathy to institutional religion, one might expect an anti-Catholic bias toward Joan or at least toward the bishops and theologians who condemned her. Instead one finds a remarkably accurate biography of the life and mission of Joan of Arc told by one of this country’s greatest storytellers. The very fact that Mark Twain wrote this book and wrote it the way he did is a powerful testimony to the attractive power of the Catholic Church’s saints. This is a book that really will inform and inspire.

A true renaissance man…and modern-day Forrest Gump.

December 30, 2020John Perry Barlow, My Life in Crazy Times. Writing for Wired magazine, he traveled to Sarajevo to write about information and the Serbo-Croatian war in the early 90’s. He writes in his book:

“They wanted me to write about the relationship between information and the war and the way in which the mass media had created a hallucination that was destroying the ability of each side to see the other’s humanity.”

If he would have stayed well, what would he be writing now, about the United States of America.

[…]

“The truth is we come into the world from the other side, which is entirely made of love, where it’s all open and could not be more open, into this place of constriction and containment and closure and dogma and terror.”

[…]

“Love forgives everything.”

Barlow died right after he finished his memoir.

“In Cyberspace, the First Amendment is a local ordinance.”

Barlow was also a lyricist for The Grateful Dead.

Desperately Needed Fundamental Change

June 10, 2020“If you want to bring in different perspectives, you’ll have a different culture & different environment that will lead you to make different decisions.”

James Bennet, recently resigned opinion editor for the NYTimes, representing collective White privilege patriarchy…father, Douglas Bennet, former NPR Director/Wesleyan University president and part of both the Carter & Clinton administrations, and brother, Michael Bennet, U.S. Senator and former U.S. Presidential candidate. -dayle

A copy of the December 23, 2018, edition of the New York Times.Robert Alexander/Getty Images

VOX

America is changing, and so is the media

The media has gone through painful periods of change before. But this time is different

By

There have always been boundaries around acceptable discourse, and the media has always been involved, in a complex and often unacknowledged way, in both enforcing and contesting them. In 1986, the media historian Daniel Hallin argued that journalists treat ideas as belonging to three spheres, each of which is governed by different rules of coverage. There’s the “sphere of consensus,” in which agreement is assumed. There’s the “sphere of deviance,” in which a view is considered universally repugnant, and it need not be entertained. And then, in the middle, is the “sphere of legitimate controversy,” wherein journalists are expected to cover all sides, and op-ed pages to represent all points of view.

The media’s week of reckoning

Last week, the New York Times op-ed section solicited and published an article by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) arguing that the US military should be deployed to “restore order to our streets.” The piece set off an internal revolt at the Times, with staffers coordinating pushback across Twitter, and led to the resignation of James Bennet, the editor of the op-ed section, and the reassignment of Jim Dao, the deputy editor.

That same week, Stan Wischnowski, the top editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, resigned after publishing an article by the paper’s architecture critic titled “Buildings Matter, Too.” David Boardman, the chair of the board that controls the Inquirer, said Wischnowski had done “remarkable” work but “leaves behind some decades-old, deep-seated and vitally important issues around diversity, equity and inclusion, issues that were not of his creation but that will likely benefit from a fresh approach.”

One interpretation of these events, favored by frustrated conservatives, is that a generation of young, woke journalists want to see the media remade along activist lines, while an older generation believes it must cover the news without fear and favor, and reflect, at the very least, the full range of views held by those in power.

“The New York Times motto is ‘all the news that’s fit to print,’” wrote the Times’s Bari Weiss. “One group emphasizes the word ‘all.’ The other, the word ‘fit.’”

Another interpretation is that the range of acceptable views isn’t narrowing so much as it’s shifting. Two decades ago, an article like Cotton’s could easily be published, an essay arguing for abolishing prisons or police would languish in the submissions pile, and a slogan like “Black Lives Matter” would be controversial. Today, Black Lives Matter is in the sphere of consensus, abolishing prisons is in legitimate controversy, and there’s a fight to move Cotton’s proposal to deploy troops against US citizens into deviance. The idea space is just as large as it’s been in the past — perhaps larger — but it is in flux, and the fight to define its boundaries is more visible.

“Those are political decisions,” says Charles Whitaker, dean of the Medill School of Journalism. “They are absolutely governed by politics — either our desire to highlight certain political views or not highlight them, or to create this impression that we’re just a marketplace of ideas.”

The media is changing because the world is changing

- First, business models built around secure local advertising monopolies collapsed into the all-against-all war for national, even global, attention that defines digital media.

- Second, the nationalization of news has changed the nature of the audience. The local business model was predicated on dominating coverage of a certain place; the national business model is about securing the loyalties of a certain kind of person.

- Third, America is in a moment of rapid demographic and generational change. Millennials are now the largest generation, and they are far more diverse and liberal than the generations that preceded them.

- Fourth, the rise of social media empowered not just the audience but, crucially, individual journalists, who now have the capacity to question their employer publicly, and alchemize staff and public discontent into a public crisis that publishers can’t ignore.

The media prefers to change in private. Now it’s changing in public.

The news media likes to pretend that it simply holds up a mirror to America as it is. We don’t want to be seen as actors crafting the political debate, agents who make decisions that shape the boundaries of the national discourse. We are, of course. We always have been.

“When you think in terms of these three spheres — sphere of consensus, of legitimate debate, and of deviancy — a new way of describing the role for journalism emerges, which is: They police what goes in which sphere,” says Jay Rosen, who teaches journalism at NYU. “That’s an ideological action they never took responsibility for, never really admitted they did, never had a language for talking about.”

“Organizations that have embraced the mantra that they need to diversify have not as quickly realized that diversifying means they have to be a fundamentally different place,” says Jelani Cobb, the Ira A. Lipman professor at the Columbia Journalism School and a staff writer at the New Yorker. “If you want to bring in different perspectives, you’ll have a different culture and different environment that will lead you to make different decisions.”

[Full Piece]

Basarab Nicolescu

May 11, 2020?

A “STOP!” – planetary and individual*

Basarab Nicolescu

‘Everything happens as if a “STOP! had been given on a planetary level. Of course, it was not this summary and unconscious entity of the infinitely small, the coronavirus, which gave this order. This order seems to emanate from the cosmic movement itself disturbed by the mad dream of the human being to dominate and manipulate Nature.

Everything stopped suddenly for half the countries of the world. This immobility did not fail to reveal to us all the flaws of globalization centered on profit and money. But which of the world’s politicians and leaders will be the ones to see? We are plunged into the blindness of the darkness of our habits of thought and the ideologies of progress, totally out of step with reality. How do you open your eyes to what’s going on? In my opinion, the only solution is the spiritual evolution of the whole of humanity. It alone could take into account all the levels of Reality and the Hidden Third.

It also happens as if a “STOP! had been given on an individual basis. We are suddenly in front of ourselves, before the mystery of our being, thus giving the exceptional opportunity of a spiritual evolution for each of us. This spiritual evolution of each human being conditions that of humanity.

We thus discover that the spiritual underdevelopment of the human being and humanity is the real cause of the crisis that we are going through and that we are going to go through.

But what spirituality is it? It is a radically new, transreligious and transcultural spirituality. Transdisciplinarity offers the tools for the establishment of such a spirituality, based on the community of destiny of all beings on earth. Two thousand years ago, the greatest visionary of all time, Jesus, asked “Love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44).

Without love nothing is possible to act on our destiny.

The world at the time refused such a message and preferred to kill Jesus. Two thousand years later, we are in exactly the same situation, on the brink of self-destruction of the species, a danger increased since by technological development and the immense means of destruction. The anthropocene without spiritual dimension will lead us to the brink of the abyss.

We must make, with great humility, a new pact of partnership with Nature and with all beings on earth – humans, animals, birds, trees, plants. We must stop defiling Nature with our excessive pride and our desire for omnipotence. All war should be declared a crime against humanity and all means of destruction should be destroyed.

All this can be understood as a utopia which goes against the principle of reality.

One possible answer is that of Michel Houellebecq: “I don’t believe in statements like” nothing will ever be the same again “. We will not wake up, after confinement, to a new world; it will be the same, only a little worse ”. If we contemplate the behavior of political leaders and public opinion in this period of crisis, it is to be feared that Michel Houellebecq is right. Politicians are returning to their usual language of mutual hostility and this will cause considerable social tension.

The media bombardment plunges us into an anxiety-provoking climate where, paradoxically, even death takes an abstract dimension: a dead person is just a number in a statistic. Nothing of the suffering of the one who dies, alone, suffocated by the coronavirus, reaches our place. This is glaring evidence of our spiritual underdevelopment.

The hidden hypothesis of Michel Houellebecq’s reasoning is the impossibility that human beings can evolve.

But another solution exists. Man must be born again if he wants to live.

Our task is immense. Let’s try not to be hypnotized by the multitude of doomsayers and apocalyptic thinkers of all kinds who predict the fall of the West and the demise of our world.

The word “Apocalypse” does not mean “end” or “destruction”, but “Revelation”. We are fortunate to have before our eyes, here and now, an extraordinary Revelation which can allow us to access Life and Meaning. I suggest reading, in these difficult times, the extraordinary book of Paule Amblard Saint John – The Apocalypse, illustrated by the tapestry of Angers [1]. Paule Amblard offers us a coherent interpretation of The Apocalypse of John by the necessity of the spiritual evolution of man. The appalling plagues which cross the text of The Apocalypse are, in truth, the torments of the human soul separated from what founds it. The Apocalypse of John is a message of longing and hope.’

[1] Paule Amblard, Saint Jean – L’Apocalypse, illustrée par la tapisserie d’Angers, Diane de Selliers Éditeur, Paris, 2017.

* Text translated from French by Gerardo del Cerro Santamaria.

Seth Godin:

Marketers used to have little choice. The only marketing was local. The local neighborhood, the local community.

Mass marketing changed that. Now, the goal was to flip the culture, all at once. Hit records, hit TV shows, products on the end cap at Target and national TV ads to support it all.

With few exceptions, that’s being replaced by a return to clusters.

The cluster might be geographic (they eat different potato chips in Tucscon than they do in Milwaukee) but they’re much more likely to be psychographic instead. What a group of people believe, who they connect with, what they hope for…

The minimal viable audience concept requires that you find your cluster and overwhelm them with delight. Choose the right cluster, show up with the right permission and sufficient magic and generosity and the idea will spread.

We’re all connected, but the future is local.

Footprints might be a fine compass, but they’re not much of a map. That’s on us.

More from Seth:

Mathematicians don’t need to check in with the head of math to find out what the talking points about fractions are this week.

That’s because fractions are fractions. Anyone can choose to do the math, and everyone will find the same truth.

Most of the progress in our culture of the last 200 years has come from using truth as a force for forward motion. Centralized proclamations are not nearly as resilient or effective as the work of countless individuals, aligned in their intention, engaging with the world.

We amplified this organizing principle when we began reporting on progress. If you’re able to encounter not just local truth but the reality as experienced by many others, collated honestly, then progress moves forward exponentially faster.

Show your work.

One of the dangers of our wide-open media culture of the last ten years has been that the signals aren’t getting through the noise.

Loud voices are drowning out useful ones. It’s difficult to determine, sometimes, who is accurately collating and correlating experience and reality and who is simply making stuff up as a way to distract us, to cause confusion and to gain influence.

I’m betting that in the long run, reality wins out. That the practical resilience that comes from experimentation produces more effective forward motion.

In the words attributed to Galileo, “Eppur si muove.”

It pays to curate the incoming, to ignore the noise and to engage with voices that are willing to show their work.

~

Thomas Merton:

The question arises: is modern man…confused and exhausted by a multitude of words, opinions, doctrines, and slogans…psychologically capable of the clarity and confidence necessary for valid prayer? Is he not so frustrated and deafened by conflicting propagandas that he has lost his capacity for deep and simple trust?

-Life and Holiness

Where men live huddled together without true communication, there seems to be greater sharing and a more genuine communion. But this is not communion, only immersion in the general meaninglessness of countless slogans and cliches related over and over again so that in the end one listens without hearing and responds without thinking. The content din of empty words and machine noises, the endless booming of loudspeakers end by making true communication and true communion almost impossible.

Each individual in the mass in insulated by thick layers of insensibility. He doesn’t hear, he doesn’t think. He does not act, he is pushed. He does not talk, he produces conventional sounds when stimulated by the appropriate noises. he does not think, he secretes cliches.

-New Seeds of Contemplation

Culture and Clichés correspondent Lynn Berger

We’re constantly told to try something new. ‘Innovate, don’t stagnate.’ But doing things two, three or 30 times creates space for reflection – and innovation. And it can even bring unexpected joy.

‘Politicians know that there are votes to be won with an appeal to what is old and familiar. And they know that this message is most effective when it is repeated endlessly: repetition is the foundation beneath propaganda.

So here’s the paradox: in order to appreciate repetition for what it is, we actually need a new sort of attention.

It’s probably impossible to achieve the level of attentiveness we bring to first times the tenth or hundredth time we do something. But it’s entirely feasible to look more attentively at repetition, not to see it as a stumbling block but as a goal in itself. Not as a copy but as a variation. I suspect that the routines and rituals that make up daily life, the “grind” we’ve learned to fear, would feel less like a slap in the face to the zeitgeist, and more like something worthwhile all on its own.

Repetition is the norm: we’re constantly repeating things, whether we want to or not. But there’s a difference between inattentively doing things again and doing things again by choice. Conscious, attentive, deliberate. With the full awareness that this matters just as much, and with the willingness to see, hear and feel different things when you feel, hear and see them again.’

A certain level of fatigue sets in. The media landscape has fragmented so much that consumers can filter their information diet to those outlets that reflect their worldview.

Marianne Williamson

We need an entirely new politics: one that shifts us from an economic to a humanitarian bottom line, from a war economy to a peace economy, from a dirty economy to a clean economy, and from who we’ve been to who we’re ready to be. #repairamerica

Dalai Lama

Change starts with us as individuals. If one individual becomes more compassionate it will influence others and so we will change the world.

‘A nation without shared truth will be hard-to-impossible to govern.’

September 1, 2019[AXIOS]

The occupier of the Oval Office, DT’s campaign and key allies plan to make allegations of bias by social media platforms a core part of their 2020 strategy, officials tell me.

- Look for ads, speeches and sustained attacks on Facebook and Twitter in particular, the sources say.

- The irony: The social platforms are created and staffed largely by liberals — but often used most effectively in politics by conservatives, the data shows.

Why it matters: DT successfully turned the vast majority of his supporters against traditional media, and hopes to do the same against the social media companies.

- Republicans’ internal data shows it stirs up the base like few other topics.

- “In the same way we’ve seen trust in legacy media organizations deteriorate over the past year, there are similarities with social media companies,” a top Republican operative involved in the effort told me.

Between the lines: The charges of overt bias by social media platforms are way overblown, several studies have found. But, if the exaggerated claims stick, it could increase the chances of regulatory action by Republicans.

- “People feel they’re being manipulated, whether it’s by what they’re being shown in their feeds, or actions the companies have taken against conservatives,” the operative said.

- “It’s easy for people to understand how these giant corporations could influence them and direct them toward a certain favored candidate.”

How tech execs see it: They know the escalation is coming, so they are cranking up outreach to leading conservatives and trying to push hard on data showing that conservative voices often outperform liberal ones.

Reality check, from Axios chief tech correspondent Ina Fried: What is real is that most of the platforms have policies against bias that some conservative figures have run afoul of.

- Managing editor Scott Rosenberg notes that Twitter is Trump’s megaphone, while Facebook is often his favorite place to run ads.

What’s next: By the time 2020 is over, trust in all sources of information will be low, and perhaps unrecoverable.

A nation without shared truth will be hard-to-impossible to govern.

MIT Management/Sloan Schools

A 4-step plan for fighting social media manipulation in elections

by Meredith Somers

Social media manipulation of voters shows no sign of abating. Two professors propose a new research agenda to fight back.

Since the 2016 presidential election, there’s been no shortage of reports about false news being shared across social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter — and with the 2020 vote only a year away, the question is not when will the misinformation strike, but how can we guard against it?

MIT professor of IT and marketing Sinan Aral and associate professor of marketing Dean Eckles propose a four-step process for researchers to measure and analyze social media manipulation, and to turn that data into a defense against future manipulation.“Without an organized research agenda that informs policy, democracies will remain vulnerable to foreign and domestic attacks,” the professors write in an article for the August 30 edition of Science magazine.

1.

Catalogue exposures to manipulation

To defend against manipulation, Aral and Eckles write, researchers need to index a variety of social media information:

- What texts, images, and video messages were advertised?

- What type of advertisement was used (organically posted, advertised, or “boosted” through paid promotion)?

- What social platforms were these texts, images, and video messages appearing on?

- When and how were they shared and re-shared by users (in this case, voters)?

2.

Combine exposure and voting behavior datasets

In the past, public voting records and social media accounts were compared using data like self-reported profile information. But this type of comparison can be improved by using location data already being collected by social media companies, the researchers write.

This could be something like matching voter registration with home addresses based on mobile location information — the same data used for marketing purposes by social media companies.

This could be something like matching voter registration with home addresses based on mobile location information — the same data used for marketing purposes by social media companies.

One challenge of studying voter behavior, Aral and Eckles write, is that the results aren’t always accurate enough to answer questions.

Social media companies already run A/B and algorithm tests, Aral and Eckles write. The same tests could be used to measure exposure effects.

3.

Calculate consequences of voting behavior changes

Aral and Eckles write that measures like predicted voter behavior — with or without exposure to misinformation — should be combined with data like geographic and demographic characteristics for a particular election. This would help with vote total estimates in a particular area.

4.

Calculate consequences of voting behavior changes

Aral and Eckles write that measures like predicted voter behavior — with or without exposure to misinformation — should be combined with data like geographic and demographic characteristics for a particular election. This would help with vote total estimates in a particular area.

Renaissance For Truth & Accuracy

August 11, 2018Boston Globe Calls For Nationwide Media Response To Trump’s Attacks On The Press

Woodstein U: Notes on the Mass Production and Questionable Education of Journalists

“There is an inextricable link between repressing the freedom of the press and repressing the freedom for civil society to campaign for their rights. Both are an attempt to repress “inconvenient truths,” silencing protesting voices, and dimming the spotlight on illegal activity perpetrated by individuals, companies, and governments in power. And both deserve the world’s attention.”

The late Ben Bagdikian, who wrote a cover story for The Atlantic in March 1977 on the so-called Woodstein phenomenon, summed it up like this: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein “were young, inexperienced, and not particularly promising in the eyes of their superiors. Working in a city and on a paper where the country’s most celebrated journalists were in top command, the two beginners beat them all and became national heroes … If they could do it, why couldn’t every high school student?”

Washington Post writers Carl Bernstein, left, and Robert Woodward, who pressed the Watergate investigation, are photographed in Washington, D.C., May 7, 1973. It was announced that The Post won the Pulitzer Prize for public service for its stories about the Watergate scandal. (AP Photo)

But one experienced news director at a major television station said: “I prefer someone who majored in sociology or architecture or art history or psychology rather than somebody who spent a year or two learning how to put a film story together. One of our best reporters was a Rhodes scholar specializing in Florentine history. Given the nature of politics in this city. I don’t think that expertise in Machiavellian politics is such a bad idea.”

The people who hire journalists say they are divided on the value of journalism schools. But what about practitioners of journalism who, with the benefit of years of experience, can look back and judge for themselves? Did journalism graduates distinguish themselves over non-journalism graduates?

I wrote to fifty-three journalists who have won Pulitzer Prizes over the last ten years. Of those who responded. 75 percent did not major in journalism, most having degrees in English. English literature, history, or philosophy. Three did not attend college.

These Pulitzer Prize-winners were largely hostile to the idea of journalism schools and most of those approving a journalism degree specified that they favored a different undergraduate degree with journalism solely in a year of graduate work.

“THE POLITICS OF DISTRACTION” TROUBLE MEDIA STUDIES PROF. KEVIN HOWLEY

August 10, 2018

[A newspaper column from DePauw University Professor Kevin Howley takes media to task for being distracted from real issues by rhetoric.]

“Ever since [DT] announced his candidacy, the news media has followed his Twitter account with all the anticipation and credulity of a child on Christmas morning,” according to Kevin Howley, professor of communication at DePauw University. In a newspaper column, Howley continues, “Eager to publish — and profit handsomely from — the latest presidential tweet storm, an obliging press corps rewards Trump’s narcissism as it normalizes his authoritarianism.”

After the president tweeted last week that Attorney General Jeff Sessions should end the ongoing ngoing Special Counsel investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, “Reporters and pundits spent the better part of the news cycle parsing the president’s words and debating whether this latest episode constitutes obstruction of justice,” Dr. Howley observes. “What’s most troubling about all of this is how willingly reporters and editors participate in Trump’s politics of distraction.”

In Howley’s view, the media’s myopic obsession with the president amount to “endless distractions that prevent us from addressing vital problems, like climate change and the health care crisis, that require immediate attention.”

The professor’s op-ed concludes, “The Romans knew a thing or two about the politics of distraction. They called it ‘bread and circuses.’ We call it ‘fake news.’ Despite, or perhaps because of the spectacle, the Roman Empire collapsed under its own imperious weight. Maybe there’s a lesson in that for the American Empire.”

You’ll find the complete text at the website of Indiana’s Kokomo Tribune.

Dick Cavett in the Digital Age

Stopping to smell the flowers with the last great intellectual talk-show host.

“Well, that’s an awkward subject matter for me, because I know all of them,” Mr. Cavett, 81, said on a recent sunny Thursday afternoon at his sprawling country house in Connecticut. “I’m not addicted to talk shows. God knows, I’ve spent enough time on them.”

As in Mr. Cavett’s 1960s and ’70s heyday, the country is in a period of turbulence, with racial tensions flaring, protests in the streets, and a fundamental ideological fissure. The hosts who have emphasized substance, who have “gone political,” have been praised and nominated for Emmys.

But “the next Cavett”? Is such a thing possible?

If only.

For three decades, Mr. Cavett was the thinking person’s Johnny Carson, embodiment of an East Coast sophisticate. He wore smart turtlenecks and double-breasted blazers, had more cultural references than a Google server and laced martini-dry witticisms into lengthy, probing talks with 20th-century luminaries including Bette Davis, James Baldwin, Mick Jagger and Jean-Luc Godard.

A Renaissance salon in a rabbit-ears era, “The Dick Cavett Show” was woke some 50 years before the term came into vogue. Viewers tuned in to see Muhammad Ali spout off about the Vietnam War or to see Yoko Ono in a 90-minute discussion with John Lennon.

While Mr. Cavett said he loathed Nixon’s politics, he called him “a brilliant, brilliant man” and was cordial to him in person. Years after Watergate, he remembers seeing the former president and his younger daughter, Julie, seated at an outdoor restaurant in Montauk, so he grabbed a menu and, posing as a waiter, began to list the specials: Yorba Linda cream pie, Whittier College soufflé.

Not his best material, Ms. Nixon told him.

The current president is perhaps the only celebrity over the age of 70 that Mr. Cavett has never met, other than being beaten by him to shrimp in a benefit buffet line years ago.

“I think all people who get to president of the United States must have something wonderful about them,” Mr. Cavett said in a mock-diplomatic tone.

“With that,” he added, “Cavett held a gun to his head and shot himself.”

AP Headline:

“Republicans promote fear, not tax cuts, in key elections”

[From space to borders, ‘fear is a contagion in a democracy.’]

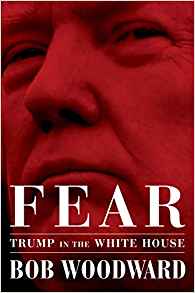

“FEAR: Trump in the White House,” by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and bestselling author Bob Woodward, will be published by Simon & Schuster on Sept. 11th.

- “Drawing from hundreds of hours of interviews with firsthand sources, contemporaneous meeting notes, files, documents and personal diaries, FEAR brings to light the explosive debates that drive decision-making in the Oval Office, the Situation Room, Air Force One and the White House residence.”

- Jonathan Karp, president and publisher of Simon & Schuster: “‘FEAR is the most acute and penetrating portrait of a sitting president ever published during the first years of an administration.”

- “FEAR is Woodward’s 19th book with Simon & Schuster, beginning with ‘All the President’s Men’ in 1974. Each of the previous 18 books he authored or co-authored has been a national nonfiction bestseller. Twelve of those have been #1 national bestsellers.”

The WashPost’s Manuel Roig-Franzia writes that the “expected tenor of the book is underscored by its unsettling cover, an extreme close-up of a squinty-eyed Trump depicted through a gauzy red filter.”“The hush-hush project derives its title from an offhand remark that then-candidate Trump made in an interview with Woodward and Post political reporter Robert Costa in April 2016.

“DT said: “Real power is, I don’t even want to use the word: ‘Fear.’

“Woodward … has privately described the remark as ‘an almost Shakespearean aside.'”

Hope Reese, JSTOR Daily

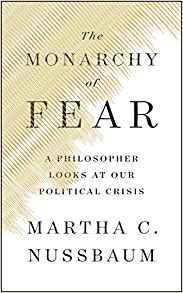

The American philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s new book, The Monarchy of Fear, examines the politics of primal fear in the 2016 election.

In November 2016, the American philosopher Martha Nussbaum was in Tokyo preparing to give a speech when she learned of the results of the U.S. presidential election. Worrying about the implications of Trump’s victory, Nussbaum, who has long studied the philosophy of emotions, realized that she “was part of the problem.”

The examination of her own reaction resulted in Nussbaum’s latest work, The Monarchy of Fear––part manifesto, part Socratic-style dialogue about the large role that fear plays in our current political era and why it represents a serious danger to democracy. Nussbaum has explored a range of emotions in her work, and this book, she tells me, makes the case that “anger, disgust, and envy…are poisoned and made more disruptive by fear.” Fear, Nussbaum argues, is both a primal emotion, an impulse felt by infants, and an emotion shaped by social context as we become older. Fear is asocial, narcissistic––and often misguided. When we fear others, Nussbaum says, we are often not taking facts and information into account––and we are often perceiving dangers that don’t exist.

“The nature of fear is that it’s very volatile and it’s very easily hijacked by rhetoric.”

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2018/07/19/civics-education-should-be-about-more-than-just-facts/

The list of what ails the U.S. politically today is long and complicated, with problems as different as vast economic inequalityand gerrymandered congressional districts. But if we’re honest with ourselves, many of the country’s most serious problems exist within us, in the hearts and minds of its people. We shelter ourselves from perspectives and facts that disagree with our own. Our politics seem more rooted in contempt and schadenfreude than empathy and reason. Politicians exploit racial, ethnic, and class divisions, leaving many Americans feeling even more targeted and disenfranchised. And a foreign adversary disseminates false information through social media because it believes that Americans cannot (or won’t really care to) distinguish reality from manipulative fiction.

Those are shortcomings in our skills and dispositions. Do public schools have a role to play in developing them? We believe they do. Schools, more than any other public institution, are charged with preparing students for the responsibilities of civic life. Parents play a critical role, too, but schools are better positioned to ensure that all children have a core set of experiences. This includes developing skills that might not be on parents’ radar, like how to evaluate news disseminated over social media. Believing that schools ought to sharpen students’ civic skills and dispositions isn’t, as Finn suggests, a product of political correctness run amok, nor is it an inherently left-of-center idea. Americans have long seen this kind of thing as a core function of schools, and even Milton Friedman’s argument for vouchers is built on a notion that schools ought to instill a common set of values.

Perhaps Finn’s critique is that teaching facts is the way to develop civic skills and dispositions, or that students develop these skills and dispositions without schools teaching them explicitly. Perhaps rather than directly teaching news and media literacy or providing students with opportunities to engage in and experience the political process, schools should stick to teaching facts and modeling nice behaviors. We see that as a missed opportunity.

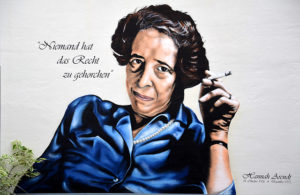

Hannah Arendt Explains How Propaganda Uses Lies to Erode All Truth & Morality: Insights from The Origins of Totalitarianism

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end—is being destroyed.

“We too,” writes Jeffrey Isaacs at The Washington Post, “live in dark times”—an allusion to another of Arendt’s sobering analyses—“even if they are different and perhaps less dark.” Arendt wrote Origins of Totalitarianism from research and observations gathered during the 1940s, a very specific historical period. Nonetheless the book, Isaacs remarks, “raises a set of fundamental questions about how tyranny can arise and the dangerous forms of inhumanity to which it can lead.” Arendt’s analysis of propaganda and the function of lies seems particularly relevant at this moment. The kinds of blatant lies she wrote of might become so commonplace as to become banal. We might begin to think they are an irrelevant sideshow. This, she suggests, would be a mistake.

H O P E

January 2, 2018‘Hope for me is deeply tied to the fact that we don’t know what will happen. This gives us grounds to act.’

“On January 18th, 1915, six months into the first world war, as all Europe was convulsed by killing and dying, Virginia Woolf wrote in her journal, ‘The future is dark, which is on the whole, the best thing the future can be, I think.’ Dark, she seems to say, as in inscrutable, not as in terrible. We often mistake the one for the other. Or we transform the future’s unknowability into something certain, the fulfillment of all our dread, the place beyond which there is no way forward. But again and again, far stranger things happen than the end of the world.

BOB GARFIELD: I want to read you a note from a father to his three daughters on election night, after the kids had pledged a compact to invest their next four years in looking inwards towards the family and relationships and the things that mattered to them the most. The note went as follows:

“Yes, we must look inwards and cherish one another, holding onto our precious love where our own values seem so under attack. But please, we must not retreat from the world, we must never stop believing in and fighting for what is just and sane. Loathe as I am to be a backseat driver in your lives, I do implore you, be courageous. Live your life fighting the fight.”

I’m intimately familiar with those sentiments because I wrote them, but notwithstanding my encouragement to my daughters, no matter what the scope of history one day will provide, in the foreseeable future we are likely as a society to go abruptly and maybe irretrievably backwards on civil rights, human rights, climate, sanity.

REBECCA SOLNIT: You’re talking about two different things, how do we feel and what do we do. And I’m not telling people how to feel, I’m telling people that there is scope for action. One of the great conundrums is that unless we believe there are possibilities we don’t act, but the possibilities only exist if we seize them. And so, a lot of what I’ve been trying to do is encourage people to recognize there is an extraordinary history of popular power in the US but also around the world. I’m not an optimist, as you said in your introduction. Optimism believes that everything will be fine, no matter what we do and, therefore, we don’t have to do a damn thing. Pessimism is the mirror image of that – that believes that everything’s going to hell in a hand basket, and it gets us off the hook. We don’t have to do anything.

Hope for me is deeply tied to the fact that we don’t know what will happen. This gives us grounds to act. And the Trump administration is such an amplifier of uncertainty. Will the guy have some kind of breakdown? Will he get impeached? Will he start World War IV? Will the Republican Party split? Will the Democratic Party find its backbone? So I think that there’s grounds to stay engaged, while being clear that terrible things are happening and we should mourn them.

You keep wanting to talk about despair and I’m just not very interested in it. The situation on climate, which I spent a lot of time looking at and trying to do something about as an activist, is really bleak but there’s wiggle room in there. You know, a lot of extraordinary stuff is happening and it’s happening in very complex ways. One thing that not very many people have noticed, because it’s a change so incremental, is that the technology of renewable non-carbon energy has evolved so dramatically over the last dozen years that we’re in a completely different place than we were at the beginning of the millennium. Bloomberg News ran a story yesterday that within the decade solar power is likely to be cheaper than coal, which is the cheapest fossil fuel. We actually have the energy solutions and they are being adapted pretty rapidly in a lot of places.

You know, we also are looking at the Antarctic ice shelf cracking. We’re looking at sea level rise. We’re looking at chaotic weather. We’re in a very deep crisis. You know, and I want people to be able to hold both of those things. We’re not talking about a future that’s already written.

What we get from the mainstream media over and over and over is a story that what we do doesn’t matter. We have had huge impacts. We have changed what constitutes what’s acceptable and ordinary in innumerable ways. You can tell the story of same-sex marriages, oh, the Supreme Court in its beneficence handed this nice thing down to us, but the Supreme Court decided that this was normal because millions of people had transformed our society in powerful ways over decades about what was normal, and so they did what seemed reasonable, but we defined what reasonable is.

The future is not yet written. What the story is depends on what we make it, and that’s really what I’m here to say.”

Rebecca Solnit is a writer, historian and activist. She’s the author of Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities.

[Full Interview on WNYC/On The Media: https://www.wnyc.org/story/otm-rebecca-solnit-hope-lies-and-making-change/]

[Photo: Prayer Wheel in Sun Valley, Idaho]

‘May the frightened cease to be afraid and those bound be freed; may the powerless find power, and may people think of benefitting one another.’ Shantideva

Perspectives on objective-less journalism.

July 18, 2017

From Maria Popova/Brainpickings

‘Fear & Loathing in Modern Media’

“There is no such thing as Objective Journalism. The phrase itself is a pompous contradiction in terms.” -Hunter S. Thompson

From 1973:

So much for Objective Journalism. Don’t bother to look for it here — not under any byline of mine; or anyone else I can think of. With the possible exception of things like box scores, race results, and stock market tabulations, there is no such thing as Objective Journalism. The phrase itself is a pompous contradiction in terms.

From 1997:

If you consider the great journalists in history, you don’t see too many objective journalists on that list. H. L. Mencken was not objective. Mike Royko, who just died. I. F. Stone was not objective. Mark Twain was not objective. I don’t quite understand this worship of objectivity in journalism. Now, just flat-out lying is different from being subjective.

Popover: ‘Flat-out lying, in fact, is something Thompson attributes to politicians whose profession he likens to a deadly addiction. In Better Than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie, the very title of which speaks to the analogy, he writes:’

Not everybody is comfortable with the idea that politics is a guilty addiction. But it is. They are addicts, and they are guilty and they do lie and cheat and steal — like all junkies. And when they get in a frenzy, they will sacrifice anything and anybody to feed their cruel and stupid habit, and there is no cure for it. That is addictive thinking. That is politics — especially in presidential campaigns. That is when the addicts seize the high ground. They care about nothing else. They are salmon, and they must spawn. They are addicts.

On Dialogue

February 24, 2017[Ralph Steadman art]

In spite of this worldwide system of linkages, there is, at this very moment, a general feeling that communication is breaking down everywhere, on an unparalleled scale…what appears [in the media] is generally at best a collection of trivial and almost unrelated fragments, while at worst, it can often be a really harmful source of confusion and misinformation.

He terms this “the problem of communication” and writes:

Different groups … are not actually able to listen to each other. As a result, the very attempt to improve communication leads frequently to yet more confusion, and the consequent sense of frustration inclines people ever further toward aggression a and violence, rather than toward mutual understanding and trust.

More from Maria Papova/brainpickings and David Bohm:

“It is clear that if we are to live in harmony with ourselves and with nature, we need to be able to communicate freely in a creative movement in which no one permanently holds to or otherwise defends his own ideas.

Language is collective. Most of our basic assumptions come from our society, including all our assumptions about how society works, about what sort of person we are supposed to be, and about relationships, institutions, and so on. Therefore we need to pay attention to thought both individually and collectively.

“Dialogue” comes from the Greek word dialogos. Logos means “the word,” or in our case we would think of the “meaning of the word.” And dia means “through” — it doesn’t mean “two.” A dialogue can be among any number of people, not just two. Even one person can have a sense of dialogue within himself, if the spirit of the dialogue is present. The picture or image that this derivation suggests is of a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which may emerge some new understanding. It’s something new, which may not have been in the starting point at all. It’s something creative. And this shared meaning is the “glue” or “cement” that holds people and societies together.

Contrast this with the word “discussion,” which has the same root as “percussion” and “concussion.” It really means to break things up. It emphasizes the idea of analysis, where there may be many points of view, and where everybody is presenting a different one — analyzing and breaking up. That obviously has its value, but it is limited, and it will not get us very far beyond our various points of view. Discussion is almost like a ping-pong game, where people are batting the ideas back and forth and the object of the game is to win or to get points for yourself…

In a dialogue, however, nobody is trying to win. Everybody wins if anybody wins. There is a different sort of spirit to it. In a dialogue, there is no attempt to gain points, or to make your particular view prevail. Rather, whenever any mistake is discovered on the part of anybody, everybody gains. It’s a situation called win-win, whereas the other game is win-lose — if I win, you lose. But a dialogue is something more of a common participation, in which we are not playing a game against each other, but with each other. In a dialogue, everybody wins.”

https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/12/05/david-bohm-on-dialogue/

The Fourth Estate

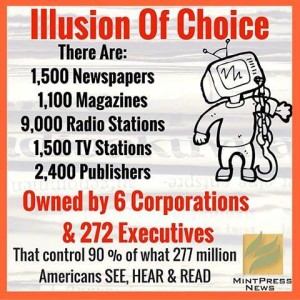

November 11, 2016The Atlantic published a piece today this Veteran’s Day, a day to honor the veterans who fought for our freedoms like the 1st Amendment, to help explain why our contemporary media are unprepared and will not be able to report on the Trump presidency. Not only are they unprepared, but they are funded by the very corporations who need to be watched. A free press is the backbone of any Democracy, it typically serves as a watchdog a country’s politics, almost an additional branch of government, hence, the 4th Estate.

The bigoted, racist, autocratic demagogue who, by anti-democratic and antiquated Electoral college will be (barring a Divine intervention) our next president. His disdain for the media is not a secret, ironically the very corporate led entity that enabled his campaign and presidency. As president-elect of the United States, he’s back to tweeting and this is what he wrote during the protests last night (Nov. 10th):

“Now professional protesters, incited by the media, are protesting. Very unfair!”

What is happening now, this new order of government and process forming in Washington post election led by an autocratic demagogue, is not rooted in our history. And we may not have a media, a free press, that can help us navigate our future.

—

Donald Trump and his surrogates have shown an uncanny ability to lie in the face of objective facts. They will now have the power of the federal government to help them.

[…]

During the 2016 presidential campaign, reporters marveled at the ability of Donald Trump and his surrogates to create an alternate reality in which statements made by the candidate had not been made at all—from his view that global warming is a hoax, to his nonexistent opposition to the Iraq War, to his refusal to say he would concede in the event of a loss, to his remarks about his relationship to Russian strongman Vladimir Putin. These are people who could argue that the sky is green without a blink. They were able to win a presidential election while doing so. Now they will have the entire apparatus of the federal government to bolster their lies, and the mainstream press is woefully unprepared to cover them.

[…]

For Trump administration mouthpieces, both public and anonymous, lies will now come with an officiality that will be difficult to contest. The total Republican control of government means that Democrats will struggle to get their objections to carry much weight, much as they did prior to the Iraq War.

[…]

With Trump, the United States has elected a president who has shown a complete disregard for free speech, arguing that his detractors do not have a “right” to criticize him. He believes the First Amendment’s protections for the press are too strong. He has a thirst for vengeance against those whom he perceives as having wronged him, and now he has the power of the federal government to pursue his vendettas. The Bush administration’s ability to manipulate the press, and the media’s willing acquiescence in the name of relating to its audience, led to catastrophe.

I want to emphasize that all administrations lie. The Lyndon Johnson administration successfully snowed the press on Vietnam. The Obama administration continually underestimated the strength of ISIS. With Trump, however, we are entering an era in which a president, prior to taking office, has already shown an ability to be entirely unbound by facts, with no political consequences.

ADAM SERWER – – The Atlantic

Full article:

Apocalypse soon.

April 15, 2016Seth Godin

It’s a bug in our operating system, and one that’s amplified by the media.

I’m listening to a speech from ten years ago, twenty years ago, forty years ago… “During these tough times… these tenuous times… these uncertain times…” And we hear about the urgency of the day, the bomb shelters, the preppers with their water tanks, the hand wringing about the next threat to civilization.

At the same time that we live in the safest world that mankind has ever experienced. Fewer deaths per capita from all the things that we worry about.

Risky? Sure it is. Every moment for the last million years has been risky. The risk has moved from Og with a rock to the chronic degeneration of our climate, but it’s clear that rehearsing and fretting and worrying about the issue of the day hasn’t done a thing to actually make it go away. Instead, we amplify the fear, market the fear and spread the fear as a form of solace, of hiding from taking action, of sharing our fear in a vain attempt to ameliorate it.

When we get nostalgic for past eras, for their culture or economy or resources, it’s interesting that we never seem to get nostalgic for their fears.

‘The enemy is fear. We think it is hate; but it is fear.’ -Gandhi