Maria Popova

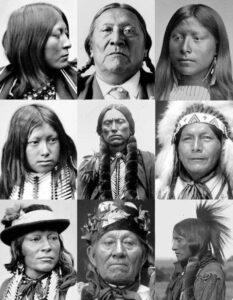

#NativeAmericanHeritageDay

November 26, 2021“Native Americans are the keepers of traditions and defenders of our natural resources. This Native American Heritage Day, I honor our culture and our ancestors. At the Interior, we will continue to include Indigenous knowledge as we protect our lands for future generations.”

-Secretary Deb Haaland, 54th Secretary of the Interior, 35th generation New Mexican, Pueblo of Laguna Tribe

[Image: Lakota Man/Twitter]

‘That’s what gods do, they spin threads of ruin through the fabric of our lives, all to make songs for generations to come.’ -Anthony Doerr ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land’, p.439

Post

C

o

l

o

n

i

a

l

Stress

D

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

PCSD

“We’re still in the genocide. It’s still happening; we’re still doing it.”

Why?

We need to look at our “individual power in relation to the world.” -Rose

Rilke: “…blessed our those who stood quietly in the rain. Theirs shall be the harvest; for them the fruits. They will outlast pomp and power, whose meaning and structures will crumble. When all else is exhausted and bled of purpose, they will lift their hands, they have survived.”

Mixed-media artist Rose B. Simpson lives and works from her home at Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico.

(This piece was commissioned for the the Conspire conference, Center for Action and Contemplation, in New Mexico.)

https://www.rosebsimpson.com/about

[Rose B. Simpson, Holding it Together (detail), 2016, sculpture]

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ

All our relations

The Last Archive

Jill Lepore, historian and Harvard professor

“Indigenous paradigm, a paradigm about relationships–all things are kin, rocks the skies, trees, family…”

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-last-archive/id1506207997?i=1000540005084

LATIMES

“The Indigenous Serrano Language Was All But Gone, This Man is Resurrecting It.”

When Ernest Siva was a boy on the Morongo Reservation in Riverside County, he listened to the music and stories of his ancestors, who had lived in Southern California long before the land was called by that name.

He recalls running around a ceremonial fire on the reservation at age 5 as a weeklong ceremony honoring those who had died the previous year culminated with the burning of images in their likeness. Dollar bills and coins were thrown into the fire in tribute as tribal elders sang songs reserved for special occasions. Siva and his cousin chased after the singed money that fluttered out of the flames, largely ignoring the traditional lyrics in the background.

The specific words and rhythms are now distant memories for the 84-year-old Siva, a Cahuilla/Serrano Native American.

Siva is working to change that. For the last 25 years, the Banning resident has been a tribal historian with the Morongo Band of Mission Indians.

CIVIL EATS

In the face of climate change and persistent droughts, a growing number of people from Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico and elsewhere are adopting the traditional farming practice.

Historic Zuni waffle gardens, circa 1919. (Photo courtesy of Kirk Bemis)

“It’s going to be difficult, but in the meantime, we still have to do what we can to find ways to adapt and live with it. And I think that the waffle gardens are one tool for us to make it through.”

(The) hope is for every household within the Zuni village to have a backyard garden, and that such a shift could cut a family’s need to shop for groceries in half.

“A small, 4-by-8 [foot] garden will get you a good four to five buckets full of corn, which is not enough to completely live off, but enough to feed our families, survive, and carry out our traditions.” He also thinks it’s important for the Zuni people to lessen dependence on grocery stores, which the pandemic showed are vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

The Resurgence of Waffle Gardens Is Helping Indigenous Farmers Grow Food with Less Water

Maria Popova

The Marginalian

“Ever since we climbed down from the trees, we have been looking up to them to understand ourselves and our place in the universe. “Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree,” Hermann Hesse wrote a century ago in his sublime sylvan love letter, affirming that “when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy.”

Centuries, millennia before Hesse — before Wangari Maathai won the Nobel Prize for her courageously enacted conviction that “a tree is a little bit of the future,” before scientists uncovered the astonishing language of trees, before Western artists saw in tree silhouettes a Rorschach test for what we are — the indigenous artists and storytellers of the Gond tribe in central India have been reverencing the secret lives of trees as portals into the inner life of nature, into the wildness of our own nature, into a supra-natural universe of myth and magic.”

The Secret Life of Trees: Stunning Sylvan Drawings by Indigenous Artists Based on Indian Mythology

The Year Earth Changed

July 26, 2021‘Narrated by David Attenborough, this timely documentary special takes a look at nature’s extraordinary response to a year of global lockdown. This love letter to planet Earth will take you from hearing birdsong in deserted cities for the first time in decades, to witnessing whales communicating in ways never before seen.

Produced by BBC Studios Natural History Unit, directed by Tom Beard, and executive produced by Mike Gunton and Alice Keens-Soper.’

AppleTV+

“One of the first documentary reflections of our strange times.”

Dayle, here. At once heartbreaking and hopeful. Not hopeful in a passive sense, as in ‘some day,’ but now. Together. Living not in dominance over, but interconnection with our planet, our species, all living beings.

Pause.

Reflect.

Our planet is gorgeous, alive, breathing. Pulsing with birth.

And it is burning. We are destroying it in present tense.

Life is being extinguished. We saw how the earth changed in days, weeks, and months early in global lockdowns WITHOUT the interaction of our destructive beings…humans. Carl Jung: “Man won’t deviate the original pattern of his being.” Is this, then, destruction?

We can give permanent pause, space, quiet, and tender mercies in our practices and consciousness, asking, what can I do in my corner of the sky? (Nod to Valarie Kaur.)

We must.

I had so much hope for our planet, for each other, in the early days of this current pandemic, our isolation. It quickly faded when the pause became political, when health and care became virtue signaling, when science became overridden by misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda, hate, disorder, power, and greed.

As a collective human body the focus became on getting ‘back to normal’ instead of shifting to what’s possible. What’s necessary.

We’re on the edge, balancing destruction with possibility. Let’s choose possibility. All of us.

The food we eat.

The cars we drive.

The Energy we use.

The resources we deplete.

The privilege we strive to achieve at the expense of other.

I want to believe there is still time.

And I want to protect all that thrived when we were silent and away.

Let’s give Gaia a chance to live, heal, and breathe. She’s given us so many.

In the silence, did you hear? Did you hear the birdsong? Did you see the animals congregate and communicate? Did you know the whales could hear again? The Himalayas could be seen again?

The future of the natural world is co-existing. We must do the one thing we can do, interconnected, to shift the planet back to health, as we inadvertently did in our absence, the year earth changed.

#

From Maria Popova, sharing a BBC interview with Carl Jung from 1959:

“…the only danger that exists is man himself — he is the great danger, and we are pitifully unaware of it. We know nothing of man — far too little. We are the origin of all coming evil [30:27].”

John Freeman and his team filmed the interview at Jung’s house at Küsnacht (near Zurich, Switzerland) in march 1959, it was broadcast in Great Britain on october 22, 1959. This film has undouptedly brought Jung to more people than any other piece of journalism and any of Jung’s own writings. Freeman was deputy editor at the “New Statesman” at the time of the interview. They formed a friendship, that continued until Jung’s death. -posted by ‘peacefulness’ on YouTube.

Jung: “We need more psychology, more study of human nature.”

We need Gaia’s nature, she does not need us. -dayle

Proust

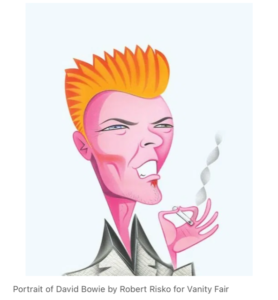

July 10, 2021David Bowie:

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Discovering morning.

Rediscovered with 4 am wake-ups for the Tour de France. ℒℴve. 🚴🏻

~dayle

“In the 1880s, long before he claimed his status as one of the greatest authors of all time, teenage Marcel Proust (July 10, 1871–November 18, 1922) filled out an English-language questionnaire given to him by his friend Antoinette, the daughter of France’s then-president, as part of her “confession album” — a Victorian version of today’s popular personality tests, designed to reveal the answerer’s tastes, aspirations, and sensibility in a series of simple questions. Proust’s original manuscript, titled “by Marcel Proust himself,” wasn’t discovered until 1924, two years after his death. In 1993, Vanity Fair resurrected the tradition and started publishing various public figures’ answers to the Proust Questionnaire on the last page of each issue. In 1998, they asked Bowie.” -Maria Popova

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Reading.

What is your most marked characteristic?

Getting a word in edgewise.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Discovering morning.

What is your greatest fear?

Converting kilometers to miles.

What historical figure do you most identify with?

Santa Claus.

Which living person do you most admire?

Elvis.

Who are your heroes in real life?

The consumer.

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

While in New York, tolerance.

Outside New York, intolerance.

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Talent.

What is your favorite journey?

The road of artistic excess.

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Sympathy and originality.

Which word or phrases do you most overuse?

“Chthonic,” “miasma.”

What is your greatest regret?

That I never wore bellbottoms.

What is your current state of mind?

Pregnant.

If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

My fear of them (wife and son excluded).

What is your most treasured possession?

A photograph held together by cellophane tape of Little Richard that I bought in 1958, and a pressed and dried chrysanthemum picked on my honeymoon in Kyoto.

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

Living in fear.

Where would you like to live?

Northeast Bali or south Java.

What is your favorite occupation?

Squishing paint on a senseless canvas.

What is the quality you most like in a man?

The ability to return books.

What is the quality you most like in a woman?

The ability to burp on command.

What are your favorite names?

Sears & Roebuck.

What is your motto?

“What” is my motto.

Thanks to Maria Popova, Brain Pickings, for the post.

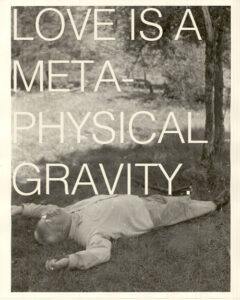

Bucky.

July 1, 2021R. Buckminster Fuller

Since 1927, whenever I am going to sleep, I always concentrate my thinking on what I call “Ever Rethinking the Lord’s Prayer.”

EVER RETHINKING THE LORD’S PRAYER

July 12, 1979

To be satisfactory to science

all definitions

must be stated

in terms of experience

I define Universe as

all of humanity’s

in-all-known-time

consciously apprehended

and communicated (to self or others)

experiences.

In using the word, God,

I am consciously employing

four clearly differentiated

from one another

experience-engendered thoughts.

Firstly I mean: —

Those experience-engendered thoughts

which are predicted upon past successions

of unexpected, human discoveries

of mathematically incisive,

physically demonstrable answers

to what theretofore had been misassumed

to be forever unanswerable

cosmic magnitude questions

wherefore I now assume it to be

scientifically manifest,

and therefore experientially reasonable that

scientifically explainable answers

may and probably will

eventually be given

to all questions

as engendered in all human thoughts

by the sum total

of all human experiences;

wherefore my first meaning for God is: —

all the experientially explained

or explainable answers

to all questions

of all time —

Secondly I mean: —

The individual’s memory

of many surprising moments

of dawning comprehensions

of an interrelated significance

to be existent

amongst a number

of what had previously seemed to be

entirely uninterrelated experiences

all of which remembered experiences

engender the reasonable assumption

of the possible existence

of a total comprehension

of the integrated significance —

the meaning —

of all experiences.

Thirdly, I mean:–

the only intellectually discoverable

a priori, intellectual integrity

indisputably manifest as

the only mathematically statable

family

of generalized principles —

cosmic laws–

thus far discovered and codified

and ever physically redemonstrable

by scientists

to be not only unfailingly operative

but to be in eternal

omni-interconsiderate,

omni-interaccommodative governance

of the complex

of everyday, naked-eye experiences

as well as of the multi-millions-fold greater range

of only instrumentally explored

infra- and ultra-tunable

micro and macro-Universe events.

Fourthly, I mean: —

All the mystery inherent

in all human experience,

which as a lifetime ratioed to eternity,

is individually limited

to almost negligible

twixt sleepings, glimpses

of only a few local episodes

of one of the infinite myriads

of concurrently and overlappingly operative

sum-totally never-ending

cosmic scenario serials

With these four meanings I now directly address God.

“Our God —

Since omni-experience is your identity

You have given us

overwhelming manifest: —

of Your complete knowledge

of Your complete comprehension

of Your complete concern

of Your complete coordination

of Your complete responsibility

of Your complete capability to cope

in absolute wisdom and effectiveness

with all problems and events

and of Your eternally unfailing reliability

so to do

Yours, Dear God,

is the only and complete glory.

By Glory I mean

the synergetic totality

of all physical and metaphysical radiation

and of all physical and metaphysical gravity

of finite

but nonunitarily conceptual

scenario Universe

in whose synergetic totality

the a priori energy potential

of both radiation and gravity

are initially equal

but whose respective

behavioral patterns are such

that radiation’s entropic, redundant disintegratings

is always less effective

than gravity’s nonredundant

syntropic integrating

Radiation is plural and differentiable,

radiation is focusable, beamable, and self-sinusing,

it is interceptible, separatist, and biasable —

ergo, has shadowed voids and vulnerabilities;

Gravity is unit and undifferentiable

Gravity is comprehensive

inclusively embracing and permeative

is nonfocusable and shadowless,

and is omni-integrative

all of which characteristics of love.

Love is metaphysical gravity.

You, Dear God,

are the totally loving intellect

ever designing

and ever daring to test

and thereby irrefutably proving

to the uncompromising satisfaction

of Your own comprehensive and incisive

knowledge of the absolute truth

that Your generalized principles

adequately accommodate any and all

special case developments,

involvements, and side effects;

wherefore Your absolutely courageous

omnirigorous and ruthless self-testing

alone can and does absolutely guarantee

total conservation

of the integrity

of eternally regenerative Universe

Your eternally regenerative scenario Universe

is the minimum complex

of totally intercomplementary

totally intertransforming

nonsimultaneous, differently frequenced

and differently enduring

feedback closures

of a finite

but nonunitarily

nonsimultaneously conceptual system

in which naught is created

and naught is lost

and all occurs

in optimum efficiency.

Total accountability and total feedback

constitute the minimum and only

perpetual motion system.

Universe is the one and only

eternally regenerative system.

To accomplish Your regenerative integrity

You give Yourself the responsibility

of eternal, absolutely continuous,

tirelessly vigilant wisdom.

Wherefore we have absolute faith and trust in You,

and we worship You

awe-inspiredly,

all-thankfully,

rejoicingly,

lovingly,

Amen.

Gratitude to quintessential researcher and synthesizer Maria Popova. -dayle

Color, Chemistry & Color

June 3, 2021From Maria Popova, Brain Pickings

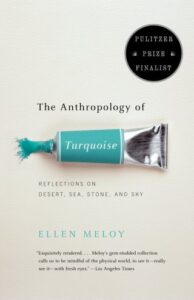

“Within every color lies a story, and stories are the binding agent of culture… The right words can come only out of the perfect space of a place you love.”

“When Carl Sagan looked at the grainy Voyager photograph of Earth seen from the far reaches of the Solar System for the very first time, he famously eulogized our Pale Blue Dot. But the color of that dot “suspended in a sunbeam” is rather between blue and green: a pixel of turquoise.

“The deep blue water of the open sea far from land is the color of emptiness and barrenness; the green water of the coastal areas, with all its varying hues, is the color of life,” Rachel Carson wrote as she illuminated the science and splendor of the marine spectrum, enriching the literary canon of history’s most beautiful meditations on the color blue.

Two centuries after Goethe wrote in his poetically beguiling, philosophically promising, but scientifically incorrect theory of color and emotion that “colors are the deeds and sufferings of light” and two generations after Frida Kahlo considered the meaning of the colors, Meloy bridges the metaphysical and the scientific across the undercurrent of the poetic: “Colors are not possessions; they are the intimate revelations of an energy field… They are light waves with mathematically precise lengths, and they are deep, resonant mysteries with boundless subjectivity.”

Meloy continues:

When a name for a color is absent from a language, it is usually blue. When a name for a color is indefinite, it is usually green. Ancient Hebrew, Welsh, Vietnamese, and, until recently, Japanese, lack a word for blue… The Icelandic word for blue and black is the same, one word that fits sea, lava, and raven.

Turquoise is ornament, jewel, talisman, tessera. It is religion. It is pawn. It is not favored for pinkie rings. It did not likely come from Turkey, its namesake, but took the name of the land it crossed on the old trade routes from Persia to Europe.

It has been shown that the words for colors enter evolving languages in this order, nearly universally: black, white, and red, then yellow and green (in either order), with green covering blue until blue comes into itself. Once blue is acquired, it eclipses green. Once named, blue pushes green into a less definite version. Green confusion is manifest in turquoise, the is-it-blue-or-is-it-green color. Despite the complexities of color names even in the same language, we somehow make sense of another person’s references. We know color as a perceptual “truth” that we imply and share without its direct experience, like feeling pain in a phantom limb or in another person’s body.

Within every color lies a story, and stories are the binding agent of culture.

It seems as if the right words can come only out of the perfect space of a place you love.

Full piece: https://www.brainpickings.org

🌺

April 20, 2021‘Love trees? Love love? “The Tree in Me” is for you – a tender painted poem about growing our capacity for joy, strength, and love.’ -Maria Popova

Walt Whitman, who considered trees the profoundest teachers in how to best be human, remembered the woman he loved and respected above all others as that rare person who was “entirely herself; as simple as nature; true, honest; beautiful as a tree is tall, leafy, rich, full, free — is a tree.”

As the child looks up to face a young woman — who could be a mother or a sister or a first love or the school janitor or the Vice President — the book ends with a subtle affirmation of William Blake’s timeless tree-tinted insistence that we see not what we look at but what we are.

The tree in me

is seed and blossom,

bark and stump…

part shade,

and part sun.

brain pickings.org

Crawl into the Promised Land

October 27, 2020New from the fierce Rosanne Cash.

“Crawl into the Promised Land” – a song that bellows in the fear-contracted chamber of the present as a mighty antidote to the collective selective memory we mistake for history and a clarion call for a more livable future.” -Maria Popova

Constellation of Chance & Choice

January 9, 2020“My life … runs back through time and space to the very beginnings of the world and to its utmost limits. In my being I sum up the earthly inheritance and the state of the world at this moment.”

Maria Popova: Perhaps our most acute awareness of the lacuna between the one life we do have and all the lives we could have had comes in the grips of our fear of missing out — those sudden and disorienting illuminations in which we recognize that parallel possibilities exists alongside our present choices. “Our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless tantrum about, the lives we were unable to live,” wrote the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips in his elegant case for the value of our unlived lives. “But the exemptions we suffer, whether forced or chosen, make us who we are.”

The garland of those exemptions strews our sense of self — our constellating experience of personal identity which, as the poet and philosopher John O’Donohue so incisively observed,”is not merely an empirical process of appropriating or digesting blocks of life.”

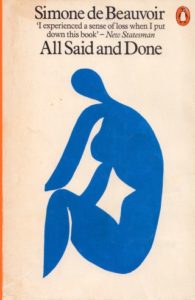

No one has captured that ultimate existential awareness more beautifully, nor with greater nuance, than the trailblazing French existentialist philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir (January 9, 1908–April 14, 1986)

The penetration of that particular ovum by that particular spermatozoon, with its implications of the meeting of my parents and before that of their birth and the births of all their forebears, had not one chance in hundreds of millions of coming about. And it was chance, a chance quite unpredictable in the present state of science, that caused me to be born a woman. From that point on, it seems to me that a thousand different futures might have stemmed from every single movement of my past: I might have fallen ill and broken off my studies; I might not have met Sartre; anything at all might have happened.

Tossed into the world, I have been subjected to its laws and its contingencies, ruled by wills other than my own, by circumstance and by history: it is therefore reasonable for me to feel that I am myself contingent. What staggers me is that at the same time I am not contingent.

If I had not been born no question would have arisen: I have to take the fact that I do exist as my starting point.

To be sure, the future of the woman I have been may turn me into someone other than myself. But in that case it would be this other woman who would be asking herself who she was. For the person who says “Here am I” there is no other coexisting possibility. Yet this necessary coincidence of the subject and his history is not enough to do away with my perplexity. My life: it is both intimately known and remote; it defines me and yet I stand outside it.

Chance … has a distinct meaning for me. I do not know where I might have been led by the paths that, as I look back, I think I might have taken but that in fact I did not take. What is certain is that I am satisfied with my fate and that I should not want it changed in any way at all. So I look upon these factors that helped me to fulfill it as so many fortunate strokes of chance.

Simone de Beauvoir on How Chance and Choice Converge to Make Us Who We Are

75-Year Study: “Good relationships keep us happier and healthier.”

May 17, 2019

Maria Popova/BrainPickings

“The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.”

Bertrand Russell

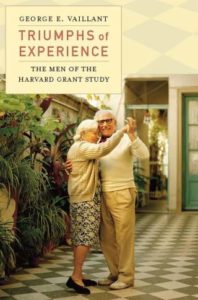

“The Study of Adult Development at the Harvard Medical School, better known as the Grant Study — the longest-running study of human happiness. Beginning in 1938 as a counterpoint to the disease model of medicine, the ongoing research set out to illuminate the conditions that enhance wellbeing by following the lives of 268 healthy sophomores from the Harvard classes between 1939 and 1944. It was a project revolutionary in both ambition and impact, nothing like it done before or since.

[…]

Little progress had been made since Walt Whitman’s prescient case for the grossly underserved human factors in healthcare and the question of what makes for a good life was cautiously left to philosophy. It’s hard for the modern mind to grasp just how daring it was for physicians to attempt to address it.

But that’s precisely what the Harvard team did. There are, of course, glaring limitations to the study — ones that tell the lamentable story of our cultural history: the original subjects were privileged white men. Nonetheless, the findings furnish invaluable insight into the core dimensions of human happiness and life satisfaction: who lives to ninety and why, what predicts self-actualization and career success, how the interplay of nature and nurture shapes who we become.”

“In this illuminating TED talk, Harvard psychologist and Grant Study director Robert Waldinger — the latest of four generations of scientists working on the project — shares what this unprecedented study has revealed, with the unflinching solidity of 75 years of data, about the building blocks of happiness, longevity, and the meaningful life.”

Ageism

February 17, 2019Ursula K. Le Guin:

For old people beauty doesn’t come free with the hormones, the way it does for the young… It has to do with who the person is.

❁

But all the same, there’s something about me that doesn’t change, hasn’t changed, through all the remarkable, exciting, alarming, and disappointing transformations my body has gone through. There is a person there who isn’t only what she looks like, and to find her and know her I have to look through, look in, look deep. Not only in space, but in time.

❁

That must be what the great artists see and paint. That must be why the tired, aged faces in Rembrandt’s portraits give us such delight: they show us beauty not skin-deep but life-deep.

[Maria Popova]

[Helen Keller surrounded by a group of young dancers at Martha Graham’s studio, including Graham herself. (1954)

Image: Perkins School for the Blind Archive]

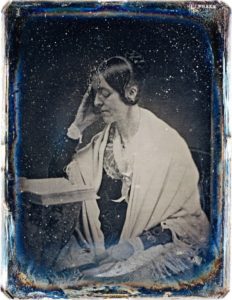

Margaret Fuller, 1810-1850

January 15, 2019This country… needs… no thin Idealist, no coarse Realist, but a man whose eye reads the heavens, while his feet step firmly on the ground, and his hands are strong and dexterous for the use of human implements… a man of universal sympathies, but self-possessed; a man who knows the region of emotion, though he is not its slave; a man to whom this world is no mere spectacle or fleeting shadow, but a great, solemn game, to be played with good heed, for its stakes are of eternal value, yet who, if his play be true, heeds not what he loses by the falsehood of others; a man who hives from the past, yet knows that its honey can but moderately avail him; whose comprehensive eye scans the present, neither infatuated by its golden lures, nor chilled by its many ventures; who possesses prescience, the gift which discerns tomorrow — when there is such a man for America, the thought which urges her on will be expressed.

From Maria Popova:

‘At age six, Margaret Fuller was reading in Latin. At twelve, she was conversing with her father in philosophy and pure mathematics. By fifteen, she had mastered French, Italian, and Greek, and was reading two or three lectures in philosophy every morning for mental discipline. In her short life, Fuller — one of the central figures in my book Figuring, and the person whom Emerson considered his greatest influence — would go on to write the foundational treatise of American women’s emancipation movement, author the most trusted literary and art criticism in America, work as the first female editor for a major New York newspaper and the only woman in the newsroom, advocate for prison reform and African American voting rights, and become America’s first foreign war correspondent, trekking through war-torn Rome while seven months pregnant. In her advocacy for African American, Native American, and women’s rights, Fuller would ardently espouse the simple, difficult truth that “while any one is base, none can be entirely free and noble.”

Ursula K.Le Guin: the invention of women, when when every woman was man.

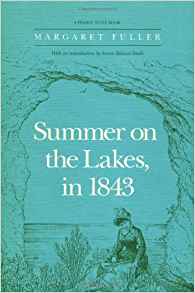

Fuller left her native New England to journey westward into the largely unfathomed frontiers of the country. She returned home transformed, awakened to new social, political, and existential realities. Eager to supplement her observations with historical research, she persuaded the Harvard library to grant her access to its book collection — the largest in the nation. No woman had previously been admitted for more than a tour. She then set about relaying her impressions and insights, ranging from a stunning portrait of Niagara Falls to a poignant account of the fate of the displaced Native American tribes with whom she sympathized and spent time. This became Fuller’s first book, Summer on the Lakes — part travelogue, part anthropological study, and part political treatise.’

2.5.19

Maria:

Figuring explores the complexities, varieties, and contradictions of love, and the human search for truth, meaning, and transcendence, through the interwoven lives of several historical figures across four centuries — beginning with the astronomer Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion, and ending with the marine biologist and author Rachel Carson, who catalyzed the environmental movement. Stretching between these figures is a cast of artists, writers, and scientists — mostly women, mostly queer — whose public contribution has risen out of their unclassifiable and often heartbreaking private relationships to change the way we understand, experience, and appreciate the universe. Among them are the astronomer Maria Mitchell, who paved the way for women in science; the sculptor Harriet Hosmer, who did the same in art; the journalist and literary critic Margaret Fuller, who sparked the feminist movement; and the poet Emily Dickinson.

Emanating from these lives are larger questions about the measure of a good life and what it means to leave a lasting mark of betterment on an imperfect world: Are achievement and acclaim enough for happiness? Is genius? Is love? Weaving through the narrative is a set of peripheral figures — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Darwin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass, Caroline Herschel, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman — and a tapestry of themes spanning music, feminism, the history of science, the rise and decline of religion, and how the intersection of astronomy, poetry, and Transcendentalist philosophy fomented the environmental movement.

Prelude:

How can we know this and still succumb to the illusion of separateness, of otherness? This veneer must have been what the confluence of accidents and atoms known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., saw through when he spoke of our “inescapable network of mutuality,” what Walt Whitman punctured when he wrote that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

There are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives.

So much of the beauty, so much of what propels our pursuit of truth, stems from the invisible connections — between ideas, between disciplines, between the denizens of a particular time and a particular place, between the interior world of each pioneer and the mark they leave on the cave walls of culture, between faint figures who pass each other in the nocturne before the torchlight of a revolution lights the new day, with little more than a half-nod of kinship and a match to change hands.

David Foster Wallace

January 25, 2018Our dread of both relationships and loneliness … has to do with angst about death, the recognition that I’m going to die, and die very much alone, and the rest of the world is going to go merrily on without me.

I’m not sure I could give you a steeple-fingered theoretical justification, but I strongly suspect a big part of real art-fiction’s job is to aggravate this sense of entrapment and loneliness and death in people, to move people to countenance it, since any possible human redemption requires us first to face what’s dreadful, what we want to deny.

Really good work probably comes out of a willingness to disclose yourself, open yourself up in spiritual and emotional ways that risk making you look banal or melodramatic or naive or unhip or sappy, and to ask the reader really to feel something. To be willing to sort of die in order to move the reader, somehow. Even now I’m scared about how sappy this’ll look in print, saying this. And the effort actually to do it, not just talk about it, requires a kind of courage I don’t seem to have yet. Maybe it’s as simple as trying to make the writing more generous and less ego-driven.

Indeed.

[Maria Popova]

Labor’s Day of Repose

September 4, 2017‘Leisure lives on affirmation. It is not the same as the absence of activity…or even as an inner quiet. It is rather like the stillness int he conversation of lovers, which is fed by their oneness.’

︶⁀°• •° ⁀︶

Maria Popova:

“We get such a kick out of looking forward to pleasures and rushing ahead to meet them that we can’t slow down enough to enjoy them when they come,” Alan Watts observed in 1970, aptly declaring us “a civilization which suffers from chronic disappointment.” Two millennia earlier, Aristotle asserted “This is the main question, with what activity one’s leisure is filled.”

[…]

So how did we end up so conflicted about cultivating a culture of leisure?

In 1948, only a year after the word “workaholic” was coined in Canada and a year before an American career counselor issued the first concentrated countercultural clarion call for rethinking work, the German philosopher Josef Pieper (May 4, 1904–November 6, 1997) penned Leisure, the Basis of Culture (public library) — a magnificent manifesto for reclaiming human dignity in a culture of compulsive workaholism, triply timely today, in an age when we have commodified our aliveness so much as to mistake making a living for having a life.

In a sentiment Pico Iyer would come to echo more than half a century later in his excellent treatise on the art of stillness, Pieper adds:

Leisure is a form of that stillness that is necessary preparation for accepting reality; only the person who is still can hear, and whoever is not still, cannot hear. Such stillness is not mere soundlessness or a dead muteness; it means, rather, that the soul’s power, as real, of responding to the real — a co-respondence, eternally established in nature — has not yet descended into words. Leisure is the disposition of perceptive understanding, of contemplative beholding, and immersion — in the real.

But there is something else, something larger, in this conception of leisure as “non-activity” — an invitation to commune with the immutable mystery of being. Pieper writes:

In leisure, there is … something of the serenity of “not-being-able-to-grasp,” of the recognition of the mysterious character of the world, and the confidence of blind faith, which can let things go as they will.

[…]

Leisure is not the attitude of the one who intervenes but of the one who opens himself; not of someone who seizes but of one who lets go, who lets himself go, and “go under,” almost as someone who falls asleep must let himself go… The surge of new life that flows out to us when we give ourselves to the contemplation of a blossoming rose, a sleeping child, or of a divine mystery — is this not like the surge of life that comes from deep, dreamless sleep?

[full article at brain pickings.org]

Sense of Self

September 2, 2017[Illustration by Salvador Dalí from his rare 1969 ‘Alice in Wonderland’ series.]

The Mystery of Personal Identity: What Makes You and Your Childhood Self the Same Person Despite a Lifetime of Change

Dissecting the philosophical conundrum of our “integrity of identity that persists over time, undergoing changes and yet still continuing to be.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

Philosophers and New Age sages have long insisted that the self is a spiritual crutch — from Alan Watts’s teachings on how our ego keeps us separate from the universe to Jack Kerouac’s passionate renunciation of the Self Illusion to Sam Harris’s contemporary case for self-transcendence. Modern psychologists have gone a step further to assert that the self is a socially constructed illusion. Whatever the case, one thing is certain and easily verifiable via personal hindsight — our present selves are unrecognizably different from our past selves and woefully flawed at making our future selves happy.

In a remarkable passage from Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity (public library), her biography of the great 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, philosopher, writer, and MacArthur Fellow Rebecca Goldstein considers the perplexity of personal identity:

Personal identity: What is it that makes a person the very person that she is, herself alone and not another, an integrity of identity that persists over time, undergoing changes and yet still continuing to be — until she does not continue any longer, at least not unproblematically?

I stare at the picture of a small child at a summer’s picnic, clutching her big sister’s hand with one tiny hand while in the other she has a precarious hold on a big slice of watermelon that she appears to be struggling to have intersect with the small o of her mouth. That child is me. But why is she me? I have no memory at all of that summer’s day, no privileged knowledge of whether that child succeeded in getting the watermelon into her mouth. It’s true that a smooth series of contiguous physical events can be traced from her body to mine, so that we would want to say that her body is mine; and perhaps bodily identity is all that our personal identity consists in. But bodily persistence over time, too, presents philosophical dilemmas.

To probe those dilemmas, Goldstein pulls into question the biographical and biological criteria we use to confirm that our childhood selves are indeed ourchildhood selves — roughly the same criteria we apply in identifying that the world’s oldest organisms are indeed continuously living individuals. Goldstein writes:

The series of contiguous physical events has rendered the child’s body so different from the one I glance down on at this moment; the very atoms that composed her body no longer compose mine. And if our bodies are dissimilar, our points of view are even more so. Mine would be as inaccessible to her … as hers is now to me. Her thought processes, prelinguistic, would largely elude me.

Yet she is me, that tiny determined thing in the frilly white pinafore. She has continued to exist, survived her childhood illnesses, the near-drowning in a rip current on Rockaway Beach at the age of twelve, other dramas. There are presumably adventures that she — that is that I — can’t undergo and still continue to be herself. Would I then be someone else or would I just no longer be? Were I to lose all sense of myself — were schizophrenia or demonic possession, a coma or progressive dementia to remove me from myself — would it be I who would be undergoing those trials, or would I have quit the premises? Would there then be someone else, or would there be no one?

She then turns to the quintessential threat to such bodily continuity, the source of our greatest existential anxiety and most profound longing:

Is death one of those adventures from which I can’t emerge as myself? The sister whose hand I am clutching in the picture is dead. I wonder every day whether she still exists.

Echoing Meghan O’Rourke’s poetic assertion that “the people we most love [become] ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created,” Goldstein writes:

A person whom one has loved seems altogether too significant a thing to simply vanish altogether from the world. A person whom one loves is a world, just as one knows oneself to be a world. How can worlds like these simply cease altogether? But if my sister does exist, then what is she, and what makes that thing that she now is identical with the beautiful girl laughing at her little sister on that forgotten day? Can she remember that summer’s day while I cannot?

Alan Watts had an answer, but Goldstein is more interested in the question itself as a gateway to our deepest humanity:

Personal identity poses a host of questions that are, in addition to being philosophical and abstract, deeply personal. It is, after all, one’s very own person that is revealed as problematic. How much more personal can it get?

Complement with pioneering educator Annemarie Roeper on the “I” of the beholder, Anaïs Nin’s bold defense of the fluid self, experimental philosopher Joshua Knobe on the mind-bending psychology of how we know who we are, and psychologist Daniel Gilbert on how your present self’s delusions limit your future self’s happiness.

The paradox of nonexistence and living.

August 10, 2017“Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be.”

Maria Popova: We continue to grapple with the paradox of our mortality. But arguably our most formidable and intense confrontation with nonexistence comes when we lose loved ones. In ‘The Year of Magical Thinking”, her harrowing record of the year following the death of her husband of four decades, John Gregory Dunne, Joan Didion, born on December 5, 1934, offers a soul-stirring meditation on grief in all its unimaginable dimensions.

Joan Didion:

“Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life. Virtually everyone who has ever experienced grief mentions this phenomenon of “waves.”

Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it. We anticipate (we know) that someone close to us could die, but we do not look beyond the few days or weeks that immediately follow such an imagined death. We misconstrue the nature of even those few days or weeks. We might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. We do not expect the shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body and mind. We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. […] In the version of grief we imagine, the model will be “healing.” A certain forward movement will prevail.

The worst days will be the earliest days. We imagine that the moment to most severely test us will be the funeral, after which this hypothetical healing will take place. When we anticipate the funeral we wonder about failing to “get through it,” rise to the occasion, exhibit the “strength” that invariably gets mentioned as the correct response to death. We anticipate needing to steel ourselves the for the moment: will I be able to greet people, will I be able to leave the scene, will I be able even to get dressed that day?

We have no way of knowing that this will not be the issue. We have no way of knowing that the funeral itself will be anodyne, a kind of narcotic regression in which we are wrapped in the care of others and the gravity and meaning of the occasion. Nor can we know ahead of the fact (and here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it and grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.”

brainpickings.org

Silent friends.

June 7, 2017For you time is never lost.

‘Perhaps because they have been our silent friends since the dawn of humanity and remain the oldest living things in the world, trees have been central to our ancient mythology and our sensemaking metaphors of science. So powerful is our bond that they can save our lives and we theirs.

That abiding bond is what Spanish multimedia storytelling of Kauri celebrates in the beautiful short film The Silent Friends.’

[Maria Popova]

Alan.

November 6, 2016There is a world of difference between an inference and a feeling. You can reason that the universe is a unity without feeling it to be so. You can establish the theory that your body is a movement in an unbroken process which includes all suns and stars, and yet continue to feel separate and lonely. For the feeling will not correspond to the theory until you have also discovered the unity of inner experience. Despite all theories, you will feel that you are isolated from life so long as you are divided within.

But you will cease to feel isolated when you recognize, for example, that you do not have a sensation of the sky: you are that sensation. For all purposes of feeling, your sensation of the sky is the sky, and there is no “you” apart from what you sense, feel, and know.

The sense of unity with the “All” is not, however, a nebulous state of mind, a sort of trance, in which all form and distinction is abolished, as if man and the universe merged into a luminous mist of pale mauve. Just as process and form, energy and matter, myself and experience, are names for, and ways of looking at, the same thing — so one and many, unity and multiplicity, identity and difference, are not mutually exclusive opposites: they are each other, much as the body is its various organs. To discover that the many are the one, and that the one is the many, is to realize that both are words and noises representing what is at once obvious to sense and feeling, and an enigma to logic and description.

[…]

When you really understand that you are what you see and know, you do not run around the countryside thinking, “I am all this.” There is simply “all this.”

Alan Watts.

[Maria Popova – – brainpickings.org]