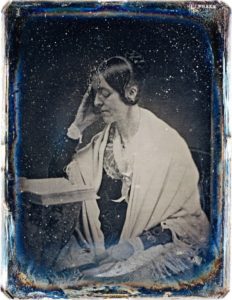

Margaret Fuller

Margaret Fuller, 1810-1850

January 15, 2019This country… needs… no thin Idealist, no coarse Realist, but a man whose eye reads the heavens, while his feet step firmly on the ground, and his hands are strong and dexterous for the use of human implements… a man of universal sympathies, but self-possessed; a man who knows the region of emotion, though he is not its slave; a man to whom this world is no mere spectacle or fleeting shadow, but a great, solemn game, to be played with good heed, for its stakes are of eternal value, yet who, if his play be true, heeds not what he loses by the falsehood of others; a man who hives from the past, yet knows that its honey can but moderately avail him; whose comprehensive eye scans the present, neither infatuated by its golden lures, nor chilled by its many ventures; who possesses prescience, the gift which discerns tomorrow — when there is such a man for America, the thought which urges her on will be expressed.

From Maria Popova:

‘At age six, Margaret Fuller was reading in Latin. At twelve, she was conversing with her father in philosophy and pure mathematics. By fifteen, she had mastered French, Italian, and Greek, and was reading two or three lectures in philosophy every morning for mental discipline. In her short life, Fuller — one of the central figures in my book Figuring, and the person whom Emerson considered his greatest influence — would go on to write the foundational treatise of American women’s emancipation movement, author the most trusted literary and art criticism in America, work as the first female editor for a major New York newspaper and the only woman in the newsroom, advocate for prison reform and African American voting rights, and become America’s first foreign war correspondent, trekking through war-torn Rome while seven months pregnant. In her advocacy for African American, Native American, and women’s rights, Fuller would ardently espouse the simple, difficult truth that “while any one is base, none can be entirely free and noble.”

Ursula K.Le Guin: the invention of women, when when every woman was man.

Fuller left her native New England to journey westward into the largely unfathomed frontiers of the country. She returned home transformed, awakened to new social, political, and existential realities. Eager to supplement her observations with historical research, she persuaded the Harvard library to grant her access to its book collection — the largest in the nation. No woman had previously been admitted for more than a tour. She then set about relaying her impressions and insights, ranging from a stunning portrait of Niagara Falls to a poignant account of the fate of the displaced Native American tribes with whom she sympathized and spent time. This became Fuller’s first book, Summer on the Lakes — part travelogue, part anthropological study, and part political treatise.’

2.5.19

Maria:

Figuring explores the complexities, varieties, and contradictions of love, and the human search for truth, meaning, and transcendence, through the interwoven lives of several historical figures across four centuries — beginning with the astronomer Johannes Kepler, who discovered the laws of planetary motion, and ending with the marine biologist and author Rachel Carson, who catalyzed the environmental movement. Stretching between these figures is a cast of artists, writers, and scientists — mostly women, mostly queer — whose public contribution has risen out of their unclassifiable and often heartbreaking private relationships to change the way we understand, experience, and appreciate the universe. Among them are the astronomer Maria Mitchell, who paved the way for women in science; the sculptor Harriet Hosmer, who did the same in art; the journalist and literary critic Margaret Fuller, who sparked the feminist movement; and the poet Emily Dickinson.

Emanating from these lives are larger questions about the measure of a good life and what it means to leave a lasting mark of betterment on an imperfect world: Are achievement and acclaim enough for happiness? Is genius? Is love? Weaving through the narrative is a set of peripheral figures — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Charles Darwin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass, Caroline Herschel, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman — and a tapestry of themes spanning music, feminism, the history of science, the rise and decline of religion, and how the intersection of astronomy, poetry, and Transcendentalist philosophy fomented the environmental movement.

Prelude:

How can we know this and still succumb to the illusion of separateness, of otherness? This veneer must have been what the confluence of accidents and atoms known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., saw through when he spoke of our “inescapable network of mutuality,” what Walt Whitman punctured when he wrote that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

There are infinitely many kinds of beautiful lives.

So much of the beauty, so much of what propels our pursuit of truth, stems from the invisible connections — between ideas, between disciplines, between the denizens of a particular time and a particular place, between the interior world of each pioneer and the mark they leave on the cave walls of culture, between faint figures who pass each other in the nocturne before the torchlight of a revolution lights the new day, with little more than a half-nod of kinship and a match to change hands.