Journalists

Dayle in Limoux – Day #60

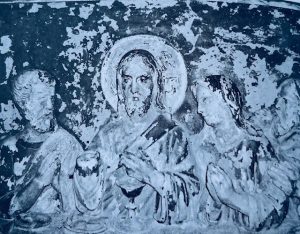

September 3, 2022From the church of Saint-Volusien in Foix, constructed in the 12th century, although the original structure was most likely constructed in the 9th. Volusien was a bishop in the regions in the late 5th century. He was persecuted by the Visigoths and placed under house arrest. He died without regaining his freedom.

‘She squatted in from of an old altar.

“Look,” she said pointing to a relief where the paint was partly peeled off. It was the scene from the Last Supper. However, in this painting there was no doubt that the person next to Yeshua was a woman. In contrast to most of the paintings, the one by Leonardo da Vinci being the most well known, in this one Mariam sat to the left of Yeshua instead of to the right which is usually the case. In this painting in the church of Foix she is looking devotedly at her partner. Everyone apart from Mariam, of course, is depicted with a beard.’

‘It may very well be that the Catholic Church in general has had its problems with Mary Magdalen. However, this does not seem to be the case here in the south of France.’

-The Manuscript, pp. 569-570

“We went under the porch supported by a few symbolically decorated pillars, which formed an impressive entrance.

“Take a look at this.”

She pointed to a star of Mariam hanging on a pillar next to us.

“And, here as well.”

“Who?”

“Yeshua and Magdalene!”

Sure enough and here they were one on each side of the same pillar…”

-The Manuscript, pp. 572-573

This book is beyond, truly. A trilogy bound as one book, the hardback, which I have, is only available from the author, Lars Muhl, in the book shop at Rennes-les-Chateau.

Gaining new levels of knowledge and taking so many notes; building bridges between my research from the last seven years for a new heart-based paradigm for journalists, intersecting a radical compassion for a homo spiritus species.

Marianne Williamson posted this earlier today from her essay titled, ‘Growing our Wings.’

When we were kids at school we had textbooks that showed human beings evolving from apes, then transforming over time into homo sapiens. On the left side of the page was a sort of hunched over looking ape, then on the right side of the page was a human being standing erect.

Okay, but I don’t think that’s the whole story; I think one day home sapiens standing erect will be seen as the middle of the page. We’re not done with evolution until we’ve evolved from ape to angel. One day, on the right side of the page there will be a human being having grown wings…

Now I don’t think those wings will be literal, of course. But I think we’re only at maybe the midway point in our evolutionary journey. We have physically evolved, but spiritually we are somewhere between an infant species and something just past barbarian. Evolution is spurring us on but we sure better hurry up.

We’re burning through all that insanity now. We have to or the species will not survive. […] The world is so clearly laboring now – a difficult labor indeed – as we struggle to give birth to the next version of who we are.

We’re not done yet. We’re transforming. No longer can we simply hug the ground. That is not our destiny. We are growing our wings.

Julian Lennon speaks to this in his own way, too, with a new album dropping on the 9th simply titled, ‘Jude’, in reference to the song Paul McCartney wrote for him when his dad, John, and his mum, Cynthia, were divorcing, ‘Hey Jude.’ This is a single from the album, ‘The Lucky Ones.’ #Jude @JulianLennon

Everyone is searching, trying to find a new religion

Some peace of mind,

Don’t wanna let go of all of my intuition

I need a sign ’cause love is blindI feel a change is coming, I know

A new revolution’s knocking on my doorEveryone is hurtin’ tryin’ a find a real solution

Well, you might find that love ain’t blind

The world is burning while we’re dancing in our own pollution

Well, is there time, or did we cross the line?We gotta find a way to get better

The only way through this is together

It’s not too late, so never say neverI know that we’re the lucky ones

Look at us, we fucked up the weather

If we unite, we’ll get through whatever

We need this world to last us forever

I know that we’re the lucky ones✧ * . * ✧ . * . *

. * . * . . ✧ .

✧ ✧ * . * . . *. .

✧ * . . ✧ . * . * .

Today was reading, writing, researching, hanging laundry (ℒℴve ! the scent of clothes after drying on the line…the best…using only the energy from the sun.),

Y

O

G

A

meditations, contemplation, and plotting the next Languedoc adventure. :)

Chapter 4

More from Marianne:

Take a good look at your life right now. If you don’t like something about it, close your eyes and imagine the life you want. Now allow yourself to focus your inner eye on the person you would have to be in order to create your preferred life.

Notice the differences in how you behave and present yourself; allow yourself to spend several seconds breathing in the new image, expanding your energy into this new mold. Hold the image for several seconds and ask the Beloved to imprint it on your subconscious mind. Do that every day for 5 minutes or so. If you share this technique with certain people, the chances are good they’ll tell you that it’s way too simple. It’s up to you what you choose to believe.

B

E

L

I

E

V

E

And for September’s Power Path, a message from Lena.

The main theme for September is: “CRISIS”

The definition of crisis comes from the word “to decide”. It is an intense time or turning point where a decision is made, there is a decisive point, and a change takes place. There is always an action component to crisis and often a need to make a choice that influences a course of action. In a healing crisis, you either get better or worse sometimes depending on that choice. In a financial crisis you may need to make hard decisions that change your usual habits and patterns. In relationship crisis you may be forced to look at some truth and face choices that produce needed change. A health crisis is often a wake-up call to change something significant in your life that puts you on a different path.

When we hear the word crisis it often brings up a negative response. In truth, crisis is often the catalyst for much needed change supporting movement towards necessary and positive evolution. Our physical nature is designed to respond to crisis with reaction and action, the instinctive response of fight or flight. Crisis often brings up fear. If we can work through the fear, there is power on the other side. This month is a good one to work proactively with the theme of crisis and use it as a catalyst for making whatever change is needed instead of being crippled by the fear it may temporarily produce.

Think of this as a month of potential breakthroughs as we are forced to go within for deep reflection and introspection regarding our values, habits, patterns, beliefs and actions. Much of the work this month will be around relationships and our perceptions of who we are, who we are with and what our work here is on this planet. Crisis that affects a community will either bring people closer together or fragment what is ready to reorganize itself differently. Crisis brings truth to the surface that can clear the decks of calcified attitudes and support new insights. Aspects of this month are conducive to clearing the mind of old beliefs and ways of thinking, opening us up to new and more inspired ideas.

As much as the crises occurring this month could be manifested outwardly, the work triggered by them is internal. Even the action component points to internal movement and change as a deep purification of the mind and our beliefs takes place. Crisis is an intense experience brought about by sudden news, a dramatic unexpected event, or some situation that has gathered enough energy to itself that you can no longer ignore it. The only way to deal effectively with crisis is to face it proactively with curiosity, confidence, trust and humor. The worst thing you can do is to withdraw into a fearful state of blame, shame or anger.

This is not an easy month but the end result of your inner process can be extremely rewarding. The key is to work with the influences instead of against them. If crisis comes into your life, watch your reactions. Get to neutral as quickly as possible, don’t take it personally, but do use it as a catalyst to do something differently. Crisis requires flexibility as your decisions may not be ones you usually make. Use curiosity as a proactive way to lean into the crisis with the intention of bringing a creative solution or decision to the process.

We do not expect every moment of this month to be full of crisis, however this is an energy that is permeating much of the common experience, and we as a collective need to move through it proactively beginning with our own inner transformation and positive change. Being in conflict can cause a crisis and the more we can resolve our own inner conflicts the more we can be a positive influence on others. This is a month of taking responsibility for our relationships, for our actions and for our personal experience of crisis.

There will also be periods of heightened awareness, increased intuition, a celebratory sense of gratitude, and rich experiences in relationship, intimacy and connection to spirit. Cherish those times of expansion and beauty, and use them as a point of reference when you find yourself in the trenches of crisis.

Balance is another necessary support this month. Practicing balance between being and doing, between the mind and the heart, and between obsessive overthinking, overcontrolling and over organizing, and the potential chaos of too loose of a container are all important. Use the natural elements as support and try and spend time between inner and outer expressions. It is good to express spiritual needs but maintain order at the same time. A good routine that handles both will be helpful during any crisis. [thepowerpath.com]

Found this on my phone, a random shot wandering the medieval streets of Arles earlier this week.

Thank goodness. :)

Bonne nuit.

♥️

The Dissident, Cyber Warfare & Justice

July 30, 2021#JusticeForJamal

THE DISSIDENT

Briarcliff Entertainment

“From the Academy Award-winning director of Icarus, Bryan Fogel, comes the untold story of the murder that shook the world.”

(You’ll want to see it…twice. #MustSee Bryan and his team, although debuting at Sundance to standing ovations and top 10 lists, could not find a distributor for eight months because, you know, Saudi Arabia. Please purchase the film and support the filmmakers, the distributor, Briarcliff, and Jamal. -Dayle)

Then, watch the podcast with Rich Roll and Bryan Fogel, particularly at the 1:20:00, ‘How cyber warfare has become a major threat…’

From the site: “Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Bryan Fogel joins Rich to discuss his new film ‘The Dissident’ a candid portrait of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the bone chilling events surrounding his murder.”

For more and how to take action:

From the site: “As of 2021, dozens of journalists are currently detained in Saudi Arabia. Journalists, Jamal Khashoggi was one of you. Keep his legacy and story alive by sharing his work widely and exposing the truth about MBS and his regime.”

The Academy Awards this year?🦗’s.

Hyperobjects and the challenges ahead. #MustRead

July 8, 2021I wrote a long essay about a pervasive feeling I have about the future. I do not think we are ready for the complex, existential challenges ahead. -Charlie Warzel

We are not ready.

On the climate crisis and other hyperobjects.

These days, I find increasingly myself caught between the worry that I’m being overly alarmist and the fear that I am stating the obvious.

I felt this most strongly in October 2020. Covid cases were surging; the presidential election was near; the far-right areas of the internet I kept an eye on were vibrating with a dark potential energy. All summer, I watched anxiously as people posted videos online of furious Americans taking to the streets. I listened in on walkie-talkie apps as so-called militia groups attempted to recruit and deploy members. News reports said sales of guns and ammo were surging.

I was seized by a deep, persistent dread that these anecdotal instances of civil conflict were a prelude to something bigger. I interviewed scholars who’ve studied revolutions and shared my fears.

Sept. 30th, 2020:

“Reading this exchange…it’s honestly very surprising to me the extent to which we haven’t seen more Kenosha like events already…”

I struggled — and ultimately failed — to put any of this into words at the time. I didn’t know how to convey these anecdotal stories into something that went beyond projecting my anxieties onto the world via the pages of the New York Times. I felt I lacked the language to proportionally describe my concern. I was legitimately worried about large-scale, sustained violent civil conflict across the United States but, if I’m being honest, I was afraid I’d come off as the extremely online, overly alarmist guy.

And yet, if you did occupy the same spaces as I did in October 2020, the specter of civil conflict would have felt just so incredibly obvious as to almost not be worth mentioning. The world was shut down, everyone was trapped inside and online, and more and more people were beginning to detach from reality. Everyone was miserable and scared and angry. Just look around!

This moment offers a window into the way that traditional conceptions and practices of journalism can break down in extraordinary times. I consider not writing this piece back in October a failure. I wrote plenty of columns around and tangential to this subject, yes. But my job is to look at the world through the lens of information and technology and to describe how those elements shape our culture and our politics. I saw something and I didn’t say all of what I thought, in part, because I couldn’t figure out how to talk about it proportionally. I was also pretty fucking scared: of being wrong, but also of being right.

Was I wrong or right? …Yes? There has not been a series of extended, mass casualty conflicts so far — no Civil War 2. But I also urge you watch this video reconstructing January 6th in full and tell me that my sleepless nights in October were a gross overreaction.

Even now, I struggle to find the adequate word to describe the moment. It makes sense: our 21st century existence is characterized by the repeated confrontation with sprawling, complex, even existential problems without straightforward or easily achievable solutions.

Theorist Timothy Morton calls the larger issues undergirding these problems “hyperobjects,” a concept so all-encompassing that it resists specific description. You could make a case that the current state of political polarization and our reality crisis falls into this category. Same for democratic backsliding and the concurrent rise of authoritarian regimes. We understand the contours of the problem, can even articulate and tweet frantically about them, yet we constantly underestimate the likelihood of their consequences. It feels unthinkable that, say, the American political system as we’ve known it will actually crumble.

Climate change is a perfect example of a hyperobject. The change in degrees of warming feels so small and yet the scale of the destruction is so massive that it’s difficult to comprehend in full. Cause and effect is simple and clear at the macro level: the planet is warming, and weather gets more unpredictable. But on the micro level of weather patterns and events and social/political upheaval, individual cause and effect can feel a bit slippery. If you are a news reporter (as opposed to a meteorologist or scientist) the peer reviewed climate science might feel impenetrable. It’s easiest to adopt a cover-your-ass position of: It’s probably climate change but I don’t know if this particular weather event is climate change.

Hyperobjects scramble all our brains, especially journalists. Journalists don’t want to be wrong. They want to react proportionally to current events and to realistically frame future ones. Too often, these desires mean that they do not explicitly say what their reporting suggest. They just insinuate it. But insinuation is not always legible.

I understand these fears and I feel them myself, professionally and personally. I think anyone who says they don’t feel them is probably lying. In fact, these fears, in the right proportion, make for what we traditionally consider a “good journalist.”

After all, many of the best journalists understand how to balance and factor uncertainty into their work. I don’t want journalists to jump to lazy conclusions. I think a deeper embrace of nuance and uncertainty is necessary not just in reporting, but in all elements of mass media.

That embrace sounds good in theory but it’s much harder in practice. How do you talk about an impending, probable-but-not-certain emergency the *right way*? Can you even do that? Can you get people ready for an uncertain, perhaps unspeakably grim future? Is anyone ready?

These questions have re-entered my brain again as I’ve scrolled the news the last few weeks. In late May and early June, there were a rash of reports about Republican efforts to restrict voting rights and halt Democrats’ expansion efforts. There was lots of warranted handwringing about the ways that Republican state legislatures are poised to consolidate power at the local level that could threaten the legitimacy of future presidential elections. Congress was unable to agree to even investigate January 6th, prompting the New Yorker to run the headline, “American Democracy Isn’t Dead Yet, but It’s Getting There.”

The overwhelming message of these pieces was that the America was running out of time on its claim of having even a remotely functioning political system. Even more worrying was the tone, which seemed to suggest it might not feel bad right now, but it’s far worse than you think. “My current level of concern is exploring countries to move to after 2024,” one political scientist told Vox in late May. Cool, cool. My personal doom indicator was a Reuters/Ipsos poll from May, as in two months ago, which found that 53% of Republicans believe Trump is the “true president.”

There are so many dire elements in the forecast for our political future. It seems like a truly formidable challenge for a country to overcome.

Which is why one piece of reporting from this past month felt like a true gut punch. In the Times, Ben Smith wrote a media column about Fox News’ Tucker Carlson, who remains a prolific source for political reporters in Washington, D.C. “Mr. Carlson’s comfortable place inside Washington media, many of the reporters who cover him say, has taken the edge off some of the coverage. It has also served as a kind of insurance policy, they say, protecting him from the marginalization that ended the Fox career of his predecessor, Glenn Beck,” Smith wrote. “‘If you open yourself up as a resource to mainstream media reporters, you don’t even have to ask them to go soft on you,’” a journalist told Smith in the piece.

I’ve reported on the far-right. I understand that the reporting process frequently brings you into contact with loathsome individuals and that, at times, these people can be quite helpful, because cynical political grifters love to turn on each other and gossip and vent just like everyone else. I’ve broken some stories, stories I’m proud of, off tips from true cretins — so take my pearl clutching with whatever grains of salt you wish.

Still, Smith’s column haunted me. You can argue Carlson is who he has always been, or that his Trump era project of (barely) laundering white nationalist talking points into mainstream political discourse is disingenuous, pandering to viewers for whom he has utter contempt. I don’t care. What I do care about is a political press that has a seemingly neutral or symbiotic relationship with a guy who beams this rhetoric into three million homes a night:

[Tucker Carlson soundbite; will not post. -dayle]

It’s worth noting that some of those same articles I read back in the fall, warning of democratic backsliding, single out Carlson as one of the animators of a dark grievance culture that threatens our social/political fabric. “The strongest factors are racial animosity, fear of becoming a white minority and the growth of white identity,” Virginia Gray, a political scientist at the University of North Carolina told the Times’ Tom Edsall, singling out a Carlson monologue from April.

It’s hard for me to square the Carlson source coziness with the host’s increasingly dangerous replacement theory and anti-vaxx rhetoric. The disconnect between the threat Carlson poses and the political media’s shrugging proximity to him fills me with a deep dread for my industry — and a very real concern that it will not be able to rise to the challenge of our moment (a shaky democratic foundation, increasingly fewer points of shared reality, a climate emergency, to name a few).

I’m not trying to dog reporters working in a shitty, gutted media ecosystem that mostly runs off algorithmic attention and online advertising that most people hate. There is no shortage of vital, journalism going on. But, structurally, there are still glaring problems with some traditional outdated journalistic norms and practices: management that still struggles to understand complex internet dynamics, a commitment to journalistic impartiality that does not work in an era where one political party has largely abandoned democracy and, in some cases, reality.

Over the last half decade, I watched political journalists and editors tie themselves in knots arguing over whether to call Trump a racist or whether the Republican party was really becoming anti-democratic or whether Trump’s election denial was a “coup.” In each instance there’s a side arguing that the other needs to calm down, that things are not as bad as they appear. I used to think these people had a lack of imagination.

Now, I see it as a strong normalcy bias. Writer Jonathan Katz calls this an ‘unthinkability’ that “pervades conversations about so many things in our moment.” Basically: we humans are good at repressing terrifying realities that feel unthinkable and steering them back into more acceptable bounds of conversation.

Climate coverage offers the clearest picture of this ‘unthinkability’ dynamic. In a clip from June 7th, CBS meteorologist Jeff Berardelli describes a heat wave stifling the east coast and the exceptional levels of draught in the West. His tone is urgent and the maps he’s gesturing to on the screen are alarming. He doesn’t mince words. “This is a climate emergency,” he tells one of the morning show anchors. It’s the kind of grim statement that you might imagine would evoke a bit of stunned silence.

Instead, the anchor smiles broadly and shakes his head in faux disbelief. “It’s very hot! I feel parched just talking about it!” he says in perfect, playful news cadence. Berardelli and the others on set offer up a classic morning show chuckle. Isn’t that something else! Banter! Onto the next segment.

[CBS warning of extreme heat soundbite.]

This is a particularly egregious example of a conventional form of media (in this case, the lighthearted morning show segment) that is woefully inadequate for the subject matter (the existential heating of the planet that will render large swaths of it hostile to human life in the near future).

In her excellent newsletter Heated, Emily Atkin has written about the systemic failureof the media to inform readers/viewers as to why it is so goddamn hot this summer. She cites the work of Colorado journalist Chase Woodruff, who surveyed recent reporting on the state’s recent heat wave and found that out of “149 local news stories written about the unprecedented hot temperatures…only 6 of those stories mentioned climate change.” The others, Atkin notes, “covered it as if it were an act of God.”

This behavior isn’t new. Back in 2018, Atkin wrote a story on the media’s failure to connect the dots on climate change. NPR’s science editor told her that “You don’t just want to be throwing around, ‘This is due to climate change, that is due to climate change.’” The editor required reporters to speak to a climate scientist before being allowed to attribute extreme temperatures to climate change. It’s an instance, Atkin argues, of “over-abundance of journalistic caution” — primarily attributable to fear. Fear of backlash from denialists, politicians, or other journalists — maybe even fear of being right.

In my mind, there’s an incredibly important distinction between embracing complexity and uncertainty in the world and what those Colorado publications, following the lead of so many others, did by not mentioning climate change — because, well, weather is complex and we don’t want to get yelled at so who’s to say?!! The problem isn’t legitimate nuance. It’s when decision makers in the media space use the existence of uncertainty as an excuse not to say what needs to be said.

Sometimes, though, mistakes aren’t nefarious. A missed or botched narrative is caused by a little bit of everything. A lot of the retroactive criticism around coronavirus coverage pre-March 2020 was that big media outlets downplayed pandemic fears because they relied heavily on credible expert sources who themselves were inclined not to be alarmists. Some in the media were doing their job just as intended and unwittingly providing false comfort. Others were providing false comfort because they didn’t want to be outliers. And another group mostly ignored the threat because platform or other media incentives directed their focus away from an unknown respiratory illness in China.

These scenarios are the product of living with and reporting on hyperobjects. The big picture — we’re losing our grip on what’s real; our political system is fraying and unsustainable; the planet is burning — is pretty clear and obvious. But many of the particulars (Is that specific hurricane climate change? Is this bill/piece of misinformation/person a threat to the democracy?) become skirmishes in the culture war.

I don’t particularly know what to do about any of this. One problem when facing down a hyperobject-sized crisis is that it overwhelms. In a recent piece, Sarah Miller articulated what it feels like to stare down existential dread on the subject of climate change. She argues that, after a certain point, traditional methods, like writing, feel futile:

“Let’s give the article…the absolute biggest benefit of the doubt and imagine that people read it and said, “Wow this is exactly how I feel, thanks for putting it into words.” What then? What would happen then? Would people be “more aware” about climate change? It’s 109 degrees in Portland right now. It’s been over 130 degrees in Baghdad several times. What kind of awareness quotient are we looking for? What more about climate change does anyone need to know? What else is there to say?

Miller’s questions ask us to consider and reconsider what our roles are right now. Yes, we have our jobs and the way we’ve been trained or conditioned or rewarded to do them and that’s all very fine and good. But what about now? Does that training hold up in remarkable, existential-feeling moments like the one we are in? Are these jobs, the way we’ve been taught to do them, important now? How do we prepare people for the uncertain, grim contours of the future? Can we do that?

I think these are the questions journalists have to be asking ourselves at every moment right now. But not just journalists. Hyperobject-sized problems impact everyone. That’s why they’re hyperobjects. And I don’t think any of us are ready. The pandemic showed us how difficult it is, at a societal level, to grasp complex ideas like, say exponential growth. And there are examples everywhere of our human inability to think longterm or pay big costs upfront to avoid catastrophe later (See: this haunting interview about the Miami condo collapse).

But not being ready isn’t quite the same as being doomed to a foregone conclusion. There’s the way we’ve done things and the way we need to do things now. How do we make up the difference between those two notions? We must be probabalistic in our predictions and understanding when they fall short. We need all need to learn to work and think on different levels, holding steadfastly to what is not up for debate, and not dividing ourselves needlessly over what is.

As good as that might sound, I feel foolish writing it. I’m not all that certain any human being can hold such conflicting notions in their head all the time. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth trying.

Living with hyperobjects is hard. I don’t think we’re ready for any of what is to come. I feel alarmist saying this. But it also feels incredibly obvious.

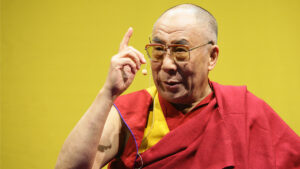

Mindful, Selfless, and Compassionate

June 5, 2021Harvard Business Review

Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Summary.

The Dalai Lama shares his observations on leadership and describes how our “strong focus on material development and accumulating wealth has led us to neglect our basic human need for kindness and care.” He offers leaders three recommendations. First, to be mindful: “When we’re under the sway of anger or attachment, we’re limited in our ability to take a full and realistic view of the situation.” Also, to be selfless: “Once you have a genuine sense of concern for others, there’s no room for cheating, bullying, or exploitation; instead you can be honest, truthful, and transparent in your conduct.” And finally, to be compassionate: “When the mind is compassionate, it is calm and we’re able to use our sense of reason practically, realistically, and with determination.”

by the Dalai Lama with Rasmus Hougaard

What can leaders do?

Be mindful

Cultivate peace of mind. As human beings, we have a remarkable intelligence that allows us to analyze and plan for the future. We have language that enables us to communicate what we have understood to others. Since destructive emotions like anger and attachment cloud our ability to use our intelligence clearly, we need to tackle them.

Fear and anxiety easily give way to anger and violence. The opposite of fear is trust, which, related to warmheartedness, boosts our self-confidence. Compassion also reduces fear, reflecting as it does a concern for others’ well-being. This, not money and power, is what really attracts friends. When we’re under the sway of anger or attachment, we’re limited in our ability to take a full and realistic view of the situation. When the mind is compassionate, it is calm and we’re able to use our sense of reason practically, realistically, and with determination.

Be selfless

We are naturally driven by self-interest; it’s necessary to survive. But we need wise self-interest that is generous and cooperative, taking others’ interests into account. Cooperation comes from friendship, friendship comes from trust, and trust comes from kindheartedness. Once you have a genuine sense of concern for others, there’s no room for cheating, bullying, or exploitation; instead, you can be honest, truthful, and transparent in your conduct.

Be compassionate

The ultimate source of a happy life is warmheartedness. Even animals display some sense of compassion. When it comes to human beings, compassion can be combined with intelligence. Through the application of reason, compassion can be extended to all 7 billion human beings. Destructive emotions are related to ignorance, while compassion is a constructive emotion related to intelligence. Consequently, it can be taught and learned.

Buddhist tradition describes three styles of compassionate leadership: the trailblazer, who leads from the front, takes risks, and sets an example; the ferryman, who accompanies those in his care and shapes the ups and downs of the crossing; and the shepherd, who sees every one of his flock into safety before himself. Three styles, three approaches, but what they have in common is an all-encompassing concern for the welfare of those they lead.”

Full piece:

Jennifer Rose

May 19, 2021“When we feed into conspiracies (whether real or fake), we reinforce the idea of external authority, while diminishing our own.”

Epic fail.

September 14, 2020“If at any point I had thought there’s something to tell the American people that they don’t know, I would do it.”

-Bob Woodward, ‘journalist’

Massive egoism.

The position of a journalist is to present the information gathered, a conduit of news and information, not a determinant of what the people have the right to know, or should, should not, learn.

“What do journalists stand for? They uphold the public’s right to know, a spirit of openness and honesty in the conduct of public business, the free flow of information and ideas, along with truthfulness, accuracy, balance, and fair play in the news.” -Jay Rosen, What are Journalist For? (p. 281)

#COVID19

Community love for local journalists.

May 13, 2020This morning outside the KBSX, Boise State Public Radio Studios.

♡

Attorney General Nominee William Barr

January 15, 2019U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar: “Will the Justice Department jail reporters for doing their jobs?”

William Barr: “I can conceive of situations where as a last resort, and where a news organization has run through a red flag…there could be a situation where someone would be held in contempt.”

Also, Barr stated today he would not fire Special Prosecutor Robert Mueller at the president’s order unless there was ’cause.’ And ’cause’ is defined as…?

1st Amendment

I. Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

ACLU in reaction to Barr’s comment on jailing journalists:

Wrong answer.

The freedom of the press is a bedrock of democratic principle. Under no circumstance should the government put journalists in jail for doing their job.”

“After much thought, what I would be willing to die for, and give my life to, is the freedom of speech. It is the open door to all other freedoms.”

Terry Tempest Williams

‘Risks in pursuit of greater truths.’

December 11, 2018[CNN Business]

“For taking great risks in pursuit of greater truths, for the imperfect but essential quest for facts that are central to civil discourse, for speaking up and for speaking out, the Guardians” are the Person of the Year, Time editor Ed Felsenthal wrote.

“As we looked at the choices, it became clear that the manipulation and abuse of truth is really the common thread in so many of this year’s major stories.” he said.

DT, not coincidentally, was the runner-up for this year’s Person of the Year title. Special counsel Robert Mueller ranked No. 3.

Karl Vick, the author of the Time’s cover story about “The Guardians,” wrote that “this ought to be a time when democracy leaps forward, an informed citizenry being essential to self-government. Instead, it’s in retreat.”

[Washington Post]

And “the story of this assault on truth is, somewhat paradoxically, one of the hardest to tell,” he added. Asked last month whom he thought Time would name, he consulted his well-thumbed narcissist’s handbook:

“I can’t imagine anybody else other than Trump,” he responded to a reporter’s question. “Can you imagine anybody else other than Trump?”

Well, yes, the editors responded, and with inspiration.

[ACLU]

“The freedom of the press is one of our most core democratic principles. Today and always we are reminded about the importance of that freedom. And to the journalists fighting to protect it: We’ve got your back.”