Hannah Arendt

Pay attention.

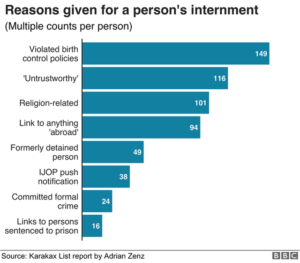

February 18, 2020The painstaking records – made up of 137 pages of columns and rows – include how often people pray, how they dress, whom they contact and how their family members behave.

China Uighurs: Detained for beards, veils and internet browsing

BBC

- Veils

- Beards

- Passport Applications

- Guilt by Association

- Family Members’ Travel

- Friends Visited

- Home Religious Atmospheres

- How Often They Prayed

- Islamic Political Leanings

- Violating China’s Strict Family Planning Laws

- Organizing Religious Study Groups

“It reveals the witch-hunt-like mindset that has been and continues to dominate social life in the region,” he said.

In early 2017, when the internment campaign began in earnest, groups of loyal Communist Party workers, known as “village-based work teams”, began to rake through Uighur society with a massive dragnet.

For every main individual, the 11th column of the spreadsheet is used to record their family relationships and their social circle.

China has long defended its actions in Xinjiang as part of an urgent response to the threat of extremism and terrorism.

[full read]

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51520622

[It’s imperative U.S. citizens be aware of this country’s language used by political leaders, pundits, and media. Be diligent. Pay attention. Think of the human rights violations already being afflicted and the reasons given. Use this report from the BBC as a transparency for not only China, but other countries as well. Political theorist Hannah Arendt writing about totalitarian leaders of the 20th century: they instilled in their followers a mixture of gullibility and cynicism…the onslaught of propaganda conditioned people to believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true. -dayle]

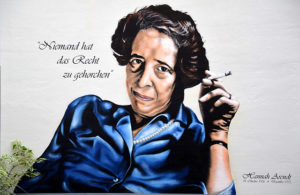

Hannah Arendt

July 28, 2018“She wrote in her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism, going on to elaborate that this “mixture of gullibility and cynicism… is prevalent in all ranks of totalitarian movements”:

In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true… The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.

“The great analysts of truth and language in politics”—writes McGill University political philosophy professor Jacob T. Levy—including “George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, Vaclav Havel—can help us recognize this kind of lie for what it is…. Saying something obviously untrue, and making your subordinates repeat it with a straight face in their own voice, is a particularly startling display of power over them. It’s something that was endemic to totalitarianism.”

Arendt and others recognized, writes Levy, that “being made to repeat an obvious lie makes it clear that you’re powerless.” She also recognized the function of an avalanche of lies to render a populace powerless to resist, the phenomenon we now refer to as “gaslighting”:

The result of a consistent and total substitution of lies for factual truth is not that the lie will now be accepted as truth and truth be defamed as a lie, but that the sense by which we take our bearings in the real world—and the category of truth versus falsehood is among the mental means to this end—is being destroyed.

Arendt’s analysis of propaganda and the function of lies seems particularly relevant at this moment. The kinds of blatant lies she wrote of might become so commonplace as to become banal. We might begin to think they are an irrelevant sideshow. This, she suggests, would be a mistake.

Open Culture, Michiko Kakutani

Remembering who.

November 11, 2017VETERAN’S DAY 2017

Action without a name, a ‘who attached to it, is meaningless.’

-Hannah Arendt

‘Eduard Kornfeld was born in 1929 near Bratislava, Slovakia. He was taken to Auschwitz and several other concentration camps. On April 29, 1945 he was freed by American troops from the Dachau camp in Germany, weighing only 60…’

[VICE NEWS]

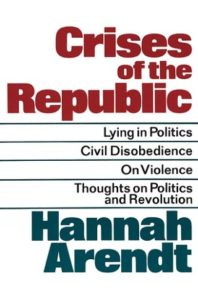

Lying in politics.

January 15, 2017‘Nowhere is this liar’s loss of perspective more damaging to public life, human possibility, and our collective progress than in politics, where complex social, cultural, economic, and psychological forces conspire to make the assault on truth traumatic on a towering scale.’

Arendt considers one particularly pernicious breed of liars — “public-relations managers in government who learned their trade from the inventiveness of Madison Avenue.”

[Note: e.g. the Pentagon budgets $5 B for PR]

In a sentiment arguably itself defeated by reality — a reality in which someone like Donald Trump sells enough of the public on enough falsehoods to get gobsmackingly close to the presidency — she writes:

The only limitation to what the public-relations man does comes when he discovers that the same people who perhaps can be “manipulated” to buy a certain kind of soap cannot be manipulated — though, of course, they can be forced by terror — to “buy” opinions and political views. Therefore the psychological premise of human manipulability has become one of the chief wares that are sold on the market of common and learned opinion.

In what is possibly the finest parenthetical paragraph ever written, and one of particularly cautionary splendor today, Arendt adds:

(Oddly enough, the only person likely to be an ideal victim of complete manipulation is the President of the United States. Because of the immensity of his job, he must surround himself with advisers … who “exercise their power chiefly by filtering the information that reaches the President and by interpreting the outside world for him.” The President, one is tempted to argue, allegedly the most powerful man of the most powerful country, is the only person in this country whose range of choices can be predetermined. This, of course, can happen only if the executive branch has cut itself off from contact with the legislative powers of Congress; it is the logical outcome in our system of government when the Senate is being deprived of, or is reluctant to exercise, its powers to participate and advise in the conduct of foreign affairs. One of the Senate’s functions, as we now know, is to shield the decision-making process against the transient moods and trends of society at large — in this case, the antics of our consumer society and the public-relations managers who cater to it.)

Arendt turns to the role of falsehood, be it deliberate or docile, in the craftsmanship of what we call history:

Unlike the natural scientist, who deals with matters that, whatever their origin, are not man-made or man-enacted, and that therefore can be observed, understood, and eventually even changed only through the most meticulous loyalty to factual, given reality, the historian, as well as the politician, deals with human affairs that owe their existence to man’s capacity for action, and that means to man’s relative freedom from things as they are. Men who act, to the extent that they feel themselves to be the masters of their own futures, will forever be tempted to make themselves masters of the past, too. Insofar as they have the appetite for action and are also in love with theories, they will hardly have the natural scientist’s patience to wait until theories and hypothetical explanations are verified or denied by facts. Instead, they will be tempted to fit their reality — which, after all, was man-made to begin with and thus could have been otherwise — into their theory, thereby mentally getting rid of its disconcerting contingency.

This squeezing of reality into theory, Arendt admonishes, is also a centerpiece of the political system, where the inherent complexity of reality is flattened into artificial oversimplification:

Much of the modern arsenal of political theory — the game theories and systems analyses, the scenarios written for imagined “audiences,” and the careful enumeration of, usually, three “options” — A, B, C — whereby A and C represent the opposite extremes and B the “logical” middle-of-the-road “solution” of the problem — has its source in this deep-seated aversion. The fallacy of such thinking begins with forcing the choices into mutually exclusive dilemmas; reality never presents us with anything so neat as premises for logical conclusions. The kind of thinking that presents both A and C as undesirable, therefore settles on B, hardly serves any other purpose than to divert the mind and blunt the judgment for the multitude of real possibilities.

But even more worrisome, Arendt cautions, is the way in which such flattening of reality blunts the judgment of government itself — nowhere more aggressively than in the overclassification of documents, which makes information available only to a handful of people in power and, paradoxically, not available to the representatives who most need that information in order to make decisions in the interest of the public who elected them. Arendt writes:

Not only are the people and their elected representatives denied access to what they must know to form an opinion and make decisions, but also the actors themselves, who receive top clearance to learn all the relevant facts, remain blissfully unaware of them. And this is so not because some invisible hand deliberately leads them astray, but because they work under circumstances, and with habits of mind, that allow them neither time nor inclination to go hunting for pertinent facts in mountains of documents, 99½ per cent of which should not be classified and most of which are irrelevant for all practical purposes.

[…]

If the mysteries of government have so befogged the minds of the actors themselves that they no longer know or remember the truth behind their concealments and their lies, the whole operation of deception, no matter how well organized its “marathon information campaigns,” in Dean Rusk’s words, and how sophisticated its Madison Avenue gimmickry, will run aground or become counterproductive, that is, confuse people without convincing them. For the trouble with lying and deceiving is that their efficiency depends entirely upon a clear notion of the truth that the liar and deceiver wishes to hide. In this sense, truth, even if it does not prevail in public, possesses an ineradicable primacy over all falsehoods.

She extrapolates the broader human vulnerability to falsehood:

The deceivers started with self-deception.

[…]

The self-deceived deceiver loses all contact with not only his audience, but also the real world, which still will catch up with him, because he can remove his mind from it but not his body.

-Maria Papova/brainpickings