Fr. Richard Rohr

Stardust & Consciousness

July 25, 2021Fr Richard Rohr:

Living in a transitional age such as ours is scary: things are falling apart, the future is unknowable, so much doesn’t cohere or make sense. We can’t seem to put order to it. This is the postmodern panic. It lies beneath most of our cynicism, our anxiety, and our aggression.

Chaos often precedes great creativity, and faith precedes great leaps into new knowledge. The pattern of transformation begins in order, but it very quickly yields to disorder and—if we stay with it long enough in love—eventual reordering. Our uncertainty is the doorway into mystery, the doorway into surrender.

Center for Action and Contemplation teacher Barbara Holmes:

The crisis begins without warning, shatters our assumptions about the way the world works, and changes our story and the stories of our neighbors. The reality that was so familiar to us is gone suddenly, and we don’t know what is happening. . . .

If life, as we experience it, is a fragile crystal orb that holds our daily routines and dreams of order and stability, then sudden and catastrophic crises shatter this illusion of normalcy. . . . I am referring to oppression, violence, pandemics, abuses of power, or natural disasters and planetary disturbances. . . .

I consider crisis contemplation to be an aspect of disorder that prepares communities for a leap toward the future. This is a leap toward our beginnings. We are not just organisms functioning on a biological level; our sphere of being also includes stardust ☆ and consciousness. We all have a spark of divinity within, a flicker of Holy Fire that can be diminished, but never extinguished.

Knock Knock,

who’s there?

Mystery and Surrender.

Please, invite me in.

- Order

- Disorder

- Reorder

“Chaos often precedes great creativity.”

K

A

I

R

O

S

“People are attracted to that that makes them feel love.”

-Marriane Williamson, A Course in Miracles

Try. Intersect great ℒℴve love with great surrender.

Inhale.

jai

A meditation from Megan McKenna on the importance of translation. Scholar and author Neil Douglas-Klotz has worked for decades with the Aramaic language, which Jesus most likely spoke as a first-century Jewish man from Nazareth. Because translation is never an exact science, Dr. Douglas-Klotz offers several possible understandings of Jesus’ teaching “Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted.”

Blessed are those in emotional turmoil; they shall be united inside by love.

Healthy are those weak and overextended for their purpose; they shall feel their inner flow of strength return.

Healed are those who weep for their frustrated desire; they shall see the face of fulfillment in a new form.

Aligned with the One are the mourners; they shall be comforted.

Turned to the Source are those feeling deeply confused by life; they shall be returned from their wandering.

Dr. Douglas-Klotz continues:

Lawile can mean “mourners” (as translated from the Greek), but in Aramaic it also carries the sense of those who long deeply for something to occur, those troubled or in emotional turmoil, or those who are weak and in want from such longing. Netbayun can mean “comforted,” but also connotes being returned from wandering, united inside by love, feeling an inner continuity, or seeing the arrival of (literally, the face of) what one longs for.

Dr. Douglas-Klotz offers this embodied prayer practice to help readers sense the powerful message of this beatitude.

When in emotional turmoil—or unable to clearly feel any emotion—experiment in this fashion: breathe in while feeling the word lawile (lay-wee-ley) [longing]; breathe out while feeling the word netbayun (net-bah-yoon) [loving]. Embrace all of what you feel and allow all emotions to wash through as though you were standing under a gentle waterfall. Follow this flow back to its source and find there the spring from which all emotion arises. At this source, consider what emotion has meaning for the moment, what action or nonaction is important now.

“You are in the time of the interim

Where everything seems withheld.

The path you took to get here has washed out.

The way forward is still concealed from you.

The old is not old enough to have died away.

The new is still too young to be born.”

-John O’Donohue

~

“To know anything fully is always to hold that part of it which is still mysterious and unknowable.” -Fr Richard Rohr

~

What has happened to our ability to dwell in unknowing, to live inside a question and coexist with the tensions of uncertainty? Where is our willingness to incubate pain and let it birth something new? What has happened to patient unfolding, to endurance?

These things are what form the ground of waiting. And if you look carefully, you’ll see that they’re also the seedbed of creativity and growth—what allows us to do the daring and to break through to newness. . . .

Creativity flourishes not in certainty but in questions. Growth germinates not in tent dwelling but in upheaval. Yet the seduction is always security rather than venturing, instant knowing rather than deliberate waiting.

-Sue Monk Kidd

When the Heart Waits: Spiritual Direction for Life’s Sacred Questions

Ahimsa.

January 4, 2021Non-Violence.

In thought, language, and behavior.

“We must disrupt harm whenever we encounter it.”

-Yogi & Activist Seane Corn

⁀︶

Ernest Holmes:

‘New arts, new sciences, new philosophies, better government, and a high civilization wait on our thoughts. The infinite energy of Life, and the possibility of our future evolution, work through our imagination and will. The time is ready the place is where we are now, and it is done unto all as they really believe and act.’

⁀︶

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin:

‘Fuse the powers of the sacred heart with the energies of the body, and you can transform everything.’

⁀︶

2 Corinthians 4:16/The Message:

‘So, we’re not giving up. How could we! Even thought on the outside it often looks like things are falling apart on us, on the inside, where GAIA is making new life, not a day goes by without Her unfolding grace.’

⁀︶

Rolph Gates & Katrina Kenison:

‘At a Native American gathering in Arizona for the 1999 summer solstice, a Hopi elder said: “There is a river flowing now, very fast. It is so great and swift that there are those who will be afraid. They will try to hold on to the shore. They will feel they are being torn apart and suffer greatly. Know that the river has its destination.

The elders say we must push off into the middle of the river, keep our eyes open and our heads above the water. See who is in there with you and celebrate.

At this time in history we are to take nothing personally, least of all ourselves, for the moment we do that, our spiritual growth comes to a halt.

The time of the lone wolf is over.

Gather yourselves; banish the work ‘struggle’ from your attitude and vocabulary. All that we do now must be done in a sacred way and in celebration. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.’

⁀︶

The Enlightened Heart, p. 86:

‘With the happiness held in one inch-square heart you can find the whole space between heaven and earth.’

⁀︶

Hildegard of Bingen:

‘Divinity is in its omniscience and omnipotence like a wheel, a circle, a whole, that can neither be understood, nor divided, nor begun, nor ended.’

⁀︶

Mark Nepo:

‘Each person is born with an unencumbered spot…free of expectation and regret…free of ambition and embarrassment, free of fear and worry…an umbilical spot of grace where we were each first touched by God, Spirt, Sophia, Gaia.

It is this spot of grace that issues pace. Psychologists call this spot the Psyche, theologians call it the Soul, Jung calls it the Seat of the Unconscious, Hindu masters call it Atman, Buddhists call it Dharma, Rilke calls it Inwardness, Sufis call it Qalb, and Jesus calls it the Center of our Love.

To know this spot of Indwardness is to know who we are, not by surface markers of identity, not by where we work to what we wear how how we like to be addressed, but by feeling our place in relation to the Infinite and by inhabiting it.

This is our lifeline task, for the nature of becoming is a constant filming over of where we’ve been, while nature of being is a constant erosion of what is not essential.

Each of us lives in the midst of this ongoing tension, growing tarnished or covered over, only to be worn back to the incorruptible spot of grace at our core.

When the film is worn through, we have moments of enlightenment, moments of whiteness, moment of satori, as the Zen sages term int, moments of clear loving when inner meets outer, moments of full integrity of being, moments of complete Oneness.

And whether the film is a veil of culture, of memory, of mental or religious training, of trauma or sophistication, the removal of that film and the restoration of that timeless spot of grace is the goal of all therapy and education.

Fr Richard Rohr:

‘The real question is “What does this have to say to me?” Those who are totally converted come to every experience and ask not whether or not they liked it, but what does it have to teach them. “What’s the message or gift in this for me? How is God in this event? Where is God in this suffering?” This is a prayer of unveiling, asking that the cruciform shape of reality be revealed to us within the very shape and circumstances of our own lives.’

Universally shared.

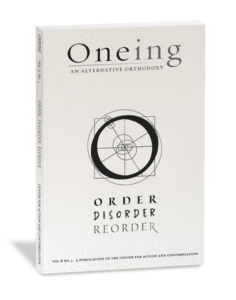

November 23, 2020Order.

Disorder.

Reorder.

Fr Richard Rohr, Center for Action and Contemplation:

Order becomes opportunity, stability melts into movement and change, status-quo government gives way to a revolution of community and neighborliness, policy bows to love, domination descends to service and sacrifice, control morphs into influence and inspiration, and vengeance and threats are transformed into forgiveness and blessing.

Contemplation: a long loving look at the real.

♡

Smart, generous and kind.

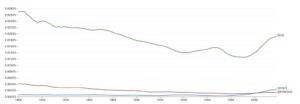

The Ngram tracks words used in books over the last 200 years. Here’s what a million authors and a billion readers think:

|

‘We may not each be called to the same work in the same ways, but we share the responsibility to repair the conscience of our nation, to stand up and stand in the gap for those who have lost hope, lost their way, lost their voice.’ Science of Mind Magazine named Stevenson their Spiritual Hero of the Year for 2020. |

In an adapted excerpt from Rohr’s A Spring Within Us, Father Richard Rohr says that mystic “simply means one who has moved from mere belief systems or belonging systems to actual inner experience. All spiritual traditions at their mature levels agree that such a movement is possible, desirable, and even available to everyone.”

“A mystic is an ordinary person who does ordinary things and experiences these moments of profound union with The Source, Mirabai Starr says.

Another sign you may be a natural mystic? An extreme affinity for nature.

Mirabai Starr: “That’s why there’s the term “Mother Earth.” For a lot of people with mystical inclinations, it’s a felt relationship with the earth, as a cherished loved one, as a relative. It’s about fully embodying our humanity and our relationship with the natural world, but that’s still a mystical experience, because we, our separate ego self dissolves into that vast mystery of The One.”

Cosmology and Nature

June 24, 2020Image Credit: Una “rete” di rami all’Arte Sella (Wood and Art in the Forest of Italy)(detail), 2008, Arte Sella, Trento, Italy.

Fr. Richard Rohr:

My friend and fellow CAC teacher Dr. Barbara Holmes has the ability to bear witness to the expansiveness of the cosmos, the major systemic shifts taking place in society, and the small and sacred moments of daily life—all at the same time. Her writing is a poetic and prophetic call for us to wake up and pay attention to everything that is happening around us.

It is time to awaken to self, society, and the cosmos, for none of us has the luxury of sleepwalking through impending cultural and scientific revolutions. In the last sermon that he preached before he was assassinated, Martin Luther King Jr. urged us to “remain awake through a great revolution.” [1] . . .

Up above our heads, there are worlds unknown and a canopy of grace, light, air, and water that supports our survival. Without realizing it, we expend massive amounts of energy to block out the vastness of our universe. This is to be expected, for, in its totality, this information can be more than human systems can take. However, by riveting our attention on the mundane, we filter out the wonder that is available with each breath.

Although we have a fascination with space and the possibility of life in other realms, we steadfastly refuse to respond when the universe invites us to broaden our lines of sight. We are beckoned by blazing sunsets and the pictures returned by powerful telescopic lenses, yet, on any given day, we court a busyness that beguiles us into focusing on the limited perspectives in our immediate space.

Today, scientific information about the universe is increasing exponentially while ethnic and racial balances within the United States are shifting radically. In the scientific realm, the epistemological foundations for hierarchy, dominance, and rationality are crumbling, while proponents of gender, class, [racial,] and sexual equity have found their public voices. . . .

We are not hamsters on a wheel, waiting to fall into the cedar shavings at the bottom of the cage. We are seekers of light and life, bearers of shadows and burdens. We are struggling to journey together toward moral fulfillment. We are learning to embrace the unfathomable darkness where God dwells with enthusiasm that equals our love of light. Physics and cosmology have metaphors and languages to help us awaken to these and other possibilities. . . . We are not just citizens of one nation or another, but of the human and cosmic community.

Awareness is the moment when we rise with eyes crusted from self-induced dreams of control, domination, victimization, and self-hatred to catch a glimpse of the divine in the face of “the other.” Then God’s self-identification, “I am that I am / I will be who I will be” (Exodus 3:14) becomes a liberating example of awareness, mutuality, and self-revelation.

Barbara teaches us that “everything belongs”—from moments of personal awakening, to mind-bending discoveries with the potential to change everything. Growing in awareness of a “Christ-soaked universe” helps us to awaken to wonder and see the divine in all things.

[1] Martin Luther King, Jr., Sermon at the National Cathedral, Washington, D.C. (March 31, 1968). See A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James M. Washington (HarperCollins: 1986), 270.

Barbara A. Holmes, Race and the Cosmos: An Invitation to View the World Differently, 2nd ed. (CAC Publishing: 2020), 42, 43, 57.

Accountability. And systemic Reformation.

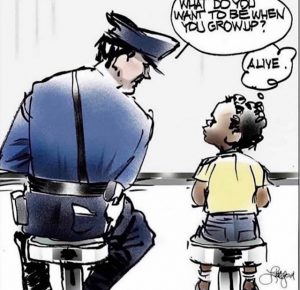

May 29, 2020Cartoon: Edward Littleford

“God is looking down on humans right now thinking, “Damn. Maybe I should try dinosaurs again?”

-Conan O’Brien

[John Oliver discusses the systems in place to investigate and hold police officers accountable for misconduct.]

Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation

A powerful example of five conversions at work is The Poor People’s Campaign, which was revived in 2018 by the Rev. Dr. William Barber II and the Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis. [1] In these paragraphs, Theoharis offers a scriptural exploration of what the Kingdom of God implies for the poor and marginalized—a movement of solidarity.

The New Testament . . . portrays the survival struggles of the marginalized, the solidarity and mutuality among different communities, and the critique of a social, political, and economic system that oppresses the vast majority of people. . . . Jesus’s teachings and actions around poverty, wealth, and power create a picture of him as a leader of a social, political, economic, and spiritual movement calling for a world without poverty, want, or oppression . . . what he named the Kingdom or Empire of God. . . .

Basilea.

The Greek word for “Kingdom of God” or “Empire of God,” basilea, has much to do with the economic order that Jesus advocated. Few would disagree that the Kingdom of God is central to the teachings of Jesus and the New Testament. However, many understand this kingdom as otherworldly and immaterial. But if we look at both the prevalence of the concept and the specific references to it in the New Testament, we can see that God’s kingdom is a real, material order, with a moral agenda different from and opposed to the reigning order of the day. The basilea is particularly present in the parables that describe how the reign of God functions differently from the Roman Empire: in God’s kingdom, there is no poverty or fear, and mutuality exists among all.

Throughout the New Testament, Jesus’s parables and stories paint a picture of a reign in which the poor and marginalized are lifted up and their needs are met, rather than being despised or ignored by those in control. . . . to model a community of mutuality and solidarity. . . .

Centuries of [New Testament] interpretation have attempted to spiritualize or minimize this good news for the poor, hiding the reality that the Bible is a book by, about, and for poor and marginalized people. It not only says that God blesses and loves the poor, but also that the poor are God’s agents and leaders in rejecting and dismantling kingdoms built upon oppression and inequality.

[1] The Poor People’s Campaign was first established by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others in 1968 to encourage leaders and citizens across the nation to stand in solidarity with the poor. https://www.poorpeoplescampaign.org/about/

Image Credit: Paulo Freire (detail), Centro de Formação, Tecnologia e Pesquisa Educacional (CEFORTEPE), SME-Campinas, Campinas, Brazil.

‘Promising us a roof and then breaking that promise might be worse than no roof at all.’

-Seth Godin

Senator Bernie Sanders:

“What gives me hope right now are the new generations of young people who dream big and do not want to settle for the status quo.”

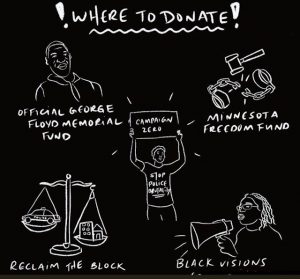

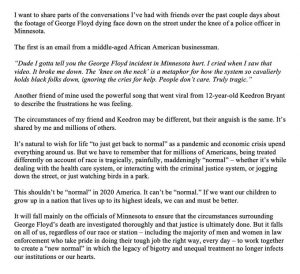

President Barack Obama:

George Floyd, 46

George Floyd moved to Minnesota “to be his best self,” as one friend put it.

Liminal Space

May 2, 2020A liminal or threshold experience can take many forms: a time of birth, a transition from life to death, or even a global pandemic that shuts down the status quo and forces us into silence and solitude. Liminal spaces, as Richard Rohr writes in the new issue of Oneing, enable us “to see beyond ourselves to the broader and more inclusive world that lies before us. When we embrace liminality, we choose hope over sleepwalking, denial, or despair. The world around us becomes again an enchanted universe.”

Liminal space is where we are betwixt and between, having left one room or stage of life but not yet entered the next. -From Farther Richard Rohr

Hardly anything turns out the way you expected it to, and you’re frequently ready to write life off as too paradoxical and too difficult to endure. Then some indescribable light fights its way through the impenetrable dark. –Paula D’Arcy

There is deep beauty in the darkness, in the unknowing, in the indescribable, if only we can open ourselves to its purpose. –LaVera Crawley

What if we can choose to experience this liminal space and time, this uncomfortable now, as a place and state of creativity, of construction and deconstruction, choice and transformation? –Sheryl Fullerton

Into this liminal realm, between the known and the unknown, we are invited to enter if we are to learn more of the way forward in our lives as individuals and as communities and nations. –John Philip Newell

Without standing on the threshold for much longer than we’re comfortable, we won’t be able to see beyond ourselves to the broader and more inclusive world that lies before us. -RR

Eco-theologian Thomas Berry says the universe is so amazing in its interrelatedness that it must have been dreamt into being. He also says our situation today as an earth community is so desperate—we are so far from knowing how to save ourselves from the ecological degradations we are a part of—that we must dream the way forward. We must summon, from the unconscious, ways of seeing that we know nothing of yet, visions that emerge from deeper within us than our conscious rational minds.

On Being.

Ocean Vuong:

“The great loss is that we can move through our whole lives, picking up phones and talking to our most beloveds, and yet, still not know who they are. Our ‘How are you?’ has failed us. We have to find something else.”

Before time.

Writer Ocean Vuong has long noticed how we grow numb to language when it’s ubiquitous, rote, rehearsed — and what’s at stake when we stop examining the words we use. Krista spoke with him at On Air Fest in Brooklyn back in March, just days before the World Health Organization declared coronavirus a global pandemic. Even then, he said “How are you?” doesn’t go deep enough.

“When you’re using language, you can create it, use it to divide people and build walls, or you can turn it into something where we can see each other more clearly, as a bridge.”

Maybe this is one way of asking: How can we choose words that allow us into one another’s lives, especially in a time when language is one of our few remaining ways to connect? Vuong beckons us toward the freshness of tomorrows, just at the tips of our tongues. -Krista Lin, Editor, the On Being Project.

Ocean Vuong is a Vietnamese-American poet, essayist and novelist. He is a recipient of the 2014 Ruth Lilly/Sargent Rosenberg fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, a 2016 Whiting Award, and the 2017 T.S. Eliot Prize for his poetry. His debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, was published in 2019. Awards: MacArthur Fellowship, T. S. Eliot Prize, Whiting Awards, Dylan Thomas Prize

Compassion, love and truth.

February 22, 2020

‘Human nature is not evil. All pleasure is not wrong. All spontaneous desires not selfish. The doctrine of original sin does not mean that human nature has been completely corrupted and that man’s freedom is always inclined to sin.

Man is neither a devil nor an angel. He is not pure spirit, but a being of flesh and spirit, subject to error and malice, but basically inclined to seek truth and goodness. He is, indeed, a sinner: but their hearts respond to love and grace. It also responds to the goodness and to the need of his fellowman.’

-Thomas Merton, Life and Holiness [1963]

If we over-use the intellectual center, then our work lies in bringing the emotional and moving centers fully online and integrating them. Wisdom is a way of knowing that goes beyond one’s mind, one’s rational understanding, and embraces the whole of a person: mind, heart, and body. These three centers must all be working, and working in harmony, as the first prerequisite to the Wisdom way of knowing.

—Cynthia Bourgeault

This essay is excerpted from W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon droop and the last tide fail,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail,

As the water all night long is crying to me.

— Arthur Symons

“Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the years all this fine contempt began to fade; for the worlds I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head,—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian,

the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten.

The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to lose effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness,—it is the contradiction of double aims. The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand to escape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart in either cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister or doctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of another people. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of ten thousand thousand people,—has sent them often wooing false gods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faith as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to a promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came,—suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood and passion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

“Shout, O children!

Shout, you’re free!

For God has bought your liberty!”

Years have passed away since then,—ten, twenty, forty; forty years of national life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthy spectre sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation’s feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastest social problem:—

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!”The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people,—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp,—like a tantalizing will-o’-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host.

The holocaust of war, the terrors of the Ku-Klux Klan, the lies of carpet-baggers, the disorganization of industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he now regarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which war had partially endowed him.

And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal to vote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dream of political power,—a powerful movement, the rise of another ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after a clouded day. It was the ideal of “book-learning”; the curiosity, born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway of Emancipation and law, steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here and there a foot had slipped or some one had fallen. To the tired climbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting-place, little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In those sombre forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself,—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully count his bastards and his prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling, sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Men call the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the natural defence of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance, purity against crime, the “higher” against the “lower” races. To which the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to so much of this strange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization, culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meekly does obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leaps beyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nigh speechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, the ridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact and wanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and the boisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to the devil,—before this there rises a sickening despair that would disarm and discourage any nation save that black host to whom “discouragement” is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came borne upon the four winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the black man’s ballot, by force or fraud,—and behold the suicide of a race! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something of good,—the more careful adjustment of education to real life, the clearer perception of the Negroes’ social responsibilities, and the sobering realization of the meaning of progress.

So dawned the time of Sturm und Drang: storm and stress to-day rocks our little boat on the mad waters of the world-sea; there is within and without the sound of conflict, the burning of body and rending of soul; inspiration strives with doubt, and faith with vain questionings. The bright ideals of the past,—physical freedom, political power, the training of brains and the training of hands,—all these in turn have waxed and waned, until even the last grows dim and overcast. Are they all wrong,—all false? No, not that, but each alone was over-simple and incomplete,—the dreams of a credulous race-childhood, or the fond imaginings of the other world which does not know and does not want to know our power. To be really true, all these ideals must be melted and welded into one. The training of the schools we need to-day more than ever,—the training of deft hands, quick eyes and ears, and above all the broader, deeper, higher culture of gifted minds and pure hearts. The power of the ballot we need in sheer self-defence,—else what shall save us from a second slavery? Freedom, too, the long-sought, we still seek,—the freedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, the freedom to love and aspire.

Work, culture, liberty,—all these we need, not singly but together, not successively but together, each growing and aiding each, and all striving toward that vaster ideal that swims before the Negro people, the ideal of human brotherhood, gained through the unifying ideal of Race; the ideal of fostering and developing the traits and talents of the Negro, not in opposition to or contempt for other races, but rather in large conformity to the greater ideals of the American Republic, in order that some day on American soil two world-races may give each to each those characteristics both so sadly lack.

We the darker ones come even now not altogether empty-handed: there are to-day no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes; there is no true American music but the wild sweet melodies of the Negro slave; the American fairy tales and folk-lore are Indian and African; and, all in all, we black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in a dusty desert of dollars and smartness. Will America be poorer if she replace her brutal dyspeptic blundering with light-hearted but determined Negro humility? or her coarse and cruel wit with loving jovial good-humor? or her vulgar music with the soul of the Sorrow Songs?

Merely a concrete test of the underlying principles of the great republic is the Negro Problem, and the spiritual striving of the freedmen’s sons is the travail of souls whose burden is almost beyond the measure of their strength, but who bear it in the name of an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers’ fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.

And now what I have briefly sketched in large outline let me on coming pages tell again in many ways, with loving emphasis and deeper detail, that men may listen to the striving in the souls of black folk.”

Maya Angelou, Elizabeth Alexander, and Arnold Rampersad — W.E.B. Du Bois and the American Soul

As Rebecca Solnit explains, hope is “coming to terms with the fact that we don’t know what will happen and that there’s maybe room for us to intervene, and that we have to let go of the certainty people seem to love more than hope and know that we don’t know what’s going to happen.” To practice hope as Solnit describes it requires acknowledging a similar incompleteness to the one that Consolmagno speaks about.

Perhaps embracing the inherent incompleteness of what we know of the world is a form of hope, allowing us to remember that there’s always something left to unfold or be discovered — and not always in the way we might’ve been conditioned to expect it. May we allow ourselves to listen, and even delight in its surprises, as we work alongside the richness of this incompleteness.

Fr. Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation:

‘The good, the true, and the beautiful are their own best argument for themselves, by themselves, and in themselves. Such deep inner knowing evokes the soul and pulls the soul into All Oneness. Incarnation is beauty, and beauty needs to be incarnate—that is specific, concrete, particular. We need to experience very particular, soul-evoking goodness in order to be shaken into what many call “realization.” It is often a momentary shock where we know we have been moved to a different plane of awareness.’

Language of the Cosmos

February 13, 2020“What does it mean to be a cosmic being, a creature of divine light and welcoming darkness, an integral part of a universe that is rife with mystery and potential?”

Dr. Barbara Holmes—my co-teacher at the Living School—has revised her incredible book Race and the Cosmos. She suggests the language of cosmology could improve on older ways of thinking and talking about race and ethnicity. The trailer is a wonderful presentation of this idea.

-Fr Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation

Keep listening.

January 17, 2020When someone disagrees with you today, stay present, listen, and then let them solve the problem.

Problems are transformed when we are present.

-Judith Hanson Lasater, PhD

“By contemplation, we mean the deliberate seeking of God through a willingness to detach from the passing self, the tyranny of emotions, the addiction to self-image, and the false promises of the world. Action, as we are using the word, means a decisive commitment toward involvement and engagement in the social order. Issues will not be resolved by mere reflection, discussion, or even prayer, nor will they be resolved only by protests, boycotts, or even, unfortunately by voting the “right” way. Rather, God “works together with” all those who love (see Romans 8:28).”

The only way out and through—for either side of any dualism, including that between action and contemplation—is a kind of universal forgiveness of Reality for being what it is; it thus becomes the bonding glue of grace which heals all the separations which law, religion, or logic can never finally or fully restore.

-Fr. Richard Rohr

Friends Committee on National Legislation

January 11, 2020‘In dangerous times like these we have to produce generations of dedicated, courageous, and creative contemplative activists who will join [the conscious collective] to bring radical healing and change to this damaged world, before it’s too late.’ -Fr. Richard Rohr

We are Quakers and friends changing public policy.

Dualism, it’s a good thing.

January 6, 2020In a nondualistic kinda way.

Fr. Richard Rohr, Center for Action and Contemplation

When I first learned contemplation in my Franciscan novitiate, I was taught a practice of silent, wordless prayer. Over the decades, I have learned there are many paths to contemplation, a myriad of ways to access nondual consciousness. Regardless how we practice—with stillness, breath, observation, chanting, walking, dancing, calm conversation—contemplation calls the ordinary thinking mind into question. We gradually come to recognize that this thing we call “thinking” does not enable us to love God and love others. We need a different operating system, and it both begins with and leads to silence.

Even through practices full of sounds and words, contemplation helps us access a foundational silence, a deep, interior openness to Presence. One of our faculty members, Barbara Holmes, writes: “An ontological silence can occupy the heart of cacophony, the interiority of celebratory worship. . . . Silence [is] the source of all being. . . . Silence is the sea that we swim in.” [1] And yet we’re often oblivious to it. Thus, the need for practice.

In my book The Naked Now, I call non-silence “dualistic thinking,” where everything is separated into opposites, like good and bad, life and death. In the West, we even believe that is what it means to be educated—to be very good at dualistic thinking. Join the debate club! But both Jesus and Buddha would call that judgmental thinking (Matthew 7:1-5), and they strongly warn us against it.

Dualistic thinking is operative almost all of the time now. It is when we choose or prefer one side and then call the other side of the equation false, wrong, heresy, or untrue.

But what we judge as wrong is often something to which we have not yet been exposed or that somehow threatens our ego. The dualistic mind splits the moment and forbids the dark side, the mysterious, the paradoxical. This is the common level of conversation that we experience in much of religion and politics and even every day conversation. It lacks humility and patience—and is the opposite of contemplation.

In contemplative practice, the Holy Spirit, [Gaia, Energy] frees us from taking sides and allows us to remain content long enough to let it teach, broaden, and enrich us in the partial darkness of every situation. We need to practice for many years and make many mistakes in the meantime to learn how to do this. Teachers of contemplation show us how to stand guard and not let our emotions and obsessive thoughts control us.

When we’re thinking nondualistically, with this guarded mind and heart, we will feel powerless for a moment, stunned into an embarrassing and welcoming silence. Then we will discover what is ours to do.

Cathari, (from Greek katharos, “pure”), also spelled CATHARS, heretical Christian sect that flourished in western Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Cathari professed a neo-Manichaean dualism—that there are two principles, one good and the other evil, and that the material world is evil.

Catharism was a heretical, Christian dualist or Gnostic revival movement that thrived in some areas of Southern Europe, particularly what is now northern Italy and southern France, between the 12th and 14th centuries.

[wikipedia]

‘You’re not crazy, you’re creative.’ ✧

November 3, 2019

A Circle expands forever

It covers all who wish to hold hands

And its size depends on each other

It is a vision of solidarity

It turns outwards to interact with the outside

And inward for self critique

A circle expands forever

It is a vision of accountability

It grows as the other is moved to grow

A circle must have a centre

But a single dot does not make a Circle

One tree does not make a forest

A circle, a vision of cooperation, mutuality and care

—Mercy Amba Oduyoye

Mercy Amba Oduyoye, “The Story of a Circle” (Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians), The Ecumenical Review, vol. 53, no. 1 (January 2001), 97. Used with permission.

✧

Fr. Richard Rohr, Center for Compassion & Contemplation

- Affirming people’s potential is more important than reminding them of their brokenness.

- The work of reconciliation should be valued over making judgments.

- Gracious behavior is more important than right belief.

- Inviting questions is more valuable than supplying answers.

- Encouraging the personal search is more important than group uniformity.

- Meeting actual needs is more important than maintaining institutions.

- Peacemaking is more important than power.

- We should care more about love and less about sex.

- Life in this world is more important than the afterlife (Eternity is Gaia’s work anyway).

✧

Rilke/New Poems:

Mohammed’s Calling

…but the angel, imperious,pointed over and over

to what was written on the page he held,

and would not held and kept insisting: read.

Then the man read, and when he did the angel bowed.

It was as if he had always been reading,

and now was able to obey and bring to pass.

✧

Alexander Stoddard/Grace Notes:

’Any profound view of the world is mysticism.’ -Albert Schweitzer

Love the questions. The bigger the questions, the better. The mysteries of life have never been understood by any human so far and never will be. The little things that make you happy, the order you put into your corner of the universe, the joy you feel from these small rituals, are mysterious. You’re not crazy; you’re creative. It’s all right if you are teased. Who cares? You do these things for yourself.

✧

A BIBLICAL ROUGH DRAFT

The New Yorker

‘Many do not know that the Bible was once a “living document,” passed orally from person to person, and from generation to generation, before finally being written down. Even the most well-known Biblical passages went through countless iterations before arriving at the final, perfect, logical, cohesive, and treasured versions we now hold dear.

Early written drafts of the Bible were the transcribed pontifications of travelling “storytellers,” who tromped from village to village in floppy sandals, swatting at flies, sipping beads of dew from the undersides of donkeys, and fighting dogs for scraps of raw meat. A close reading of the earliest known transcription of a popular excerpt from the Book of Matthew reveals that the “narrator” is suffering from low blood sugar. No doubt a syphilitic holy man dressed in desert rags, he searches in vain for just the right metaphor, a well-aimed zinger with which to make his point. The toil that the poor fellow suffers in so doing undercuts the very principle he is straining to illustrate.’

[Full essay]

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/11/04/a-biblical-rough-draft