Dialogue

Korby Lenker.

October 18, 2020

|

Dialogue. And listen.

October 10, 2020And lead.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg “knew the power of example—that if you live your own life according to your principles, others will follow,” writes her former clerk, Ryan Y. Park, Solicitor General of North Carolina.

The Atlantic

My Friend and Boss, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

“A big deal in the revival of local news: Nonprofit Mountain State Spotlight

Dialoging.

Dr. David Bohm:

“Dialogue is really aimed at going into the whole thought process and changing the way the thought process occurs collectively. We haven’t really paid much attention to thought as a process. We have engaged in thoughts, but we have only paid attention to the content, not to the process.

It is proposed that a form of free dialogue may well be one of the most effective ways of investigating the crisis which faces society, and indeed the whole of human nature and consciousness today. Moreover, it may turn out that such a form of free exchange of ideas and information is of fundamental relevance for transforming culture and freeing it of destructive misinformation, so that creativity can be liberated.”

Leah Garces:

The first lesson I learned is that we have to become comfortable with being uncomfortable. Only talking to people who agree with us, it’s not going to get us to the solution. We have to be willing to enter other people’s space. Because quite often, the enemy has the power to change the problem that we’re trying to solve.

The world’s smallest and biggest problems, they won’t be solved by beating down our enemies but by finding these win-win pathways together. It does require us to let go of that idea of us versus them and realize there’s only one us, all of us, against an unjust system. And it is difficult, and messy, and uncomfortable.

Seth Godin:

The arc and the arch.

They sound similar, but they’re not.

An arc, like an arch, is bent. The strength comes from that bend.

But the arc doesn’t have to be supported at both ends, and the arc is more flexible. The arc can take us to parts unknown, yet it has a trajectory.

An arch, on the other hand, is a solid structure. It’s a bridge that others have already walked over.

Our life is filled with both. We’re trained on arches, encouraged to seek them out.

But an arc, which comes from “arrow,” is the rare ability to take flight and to go further than you or others expected.

HOW TO HAVE A CONVERSATION WITH YOUR POLITICAL OPPONENTS

SANNE BLAUW

This story is from Strangers in Their Own Land by Arlie Hochschild.

‘For this book, the professor emerita of sociology immersed herself in the American political right wing. Over the course of five years, she regularly stayed in ultraconservative “Bayou Country” in Louisiana. She herself comes from lefter than left Berkeley, California. She couldn’t have left her bubble any further behind.

‘When left-wing sociologist Arlie Hochschild went to live in a right-wing stronghold in the American South, she was entering “enemy” territory.

But, by listening to the people there – instead of arguing against them – she distilled a clear picture: right-wing Trump supporters felt like victims of a society that had left them behind.

In an era where debate has descended into a televised shouting match, it’s easy to feel like you’re at war with people who disagree with you.

But Hochschild learned that by laying down our arms and trying to understand, even empathise with, our political opponents, we can learn how to have constructive political conversations.’

You don’t have to agree with political opponents to understand where they’re coming from

‘Having a heart-to-heart conversation with an ideological opponent can feel uncomfortable – unsafe even. But sociologist Arlie Hochschild proves that it pays off. She immersed herself in a conservative stronghold in the Southern United States for five years and wrote a book about it.’

Not everyone agrees with this approach, Hochschild said during a 2016 interview with Ezra Klein. It can feel as though you’re surrendering, laying down your weapons and walking over to the enemy. But, she says: “if you want to compare it to anything, it’s a diplomatic mission. It’s saying: look, we can work this out, let’s see what the basis of that could be”.

Whether it’s about corona, climate or benefits, let’s carry out these diplomatic missions more often. That doesn’t mean you have to agree with each other, but at least you’re making a genuine attempt to understand the other person.’

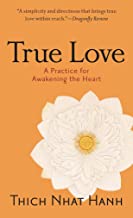

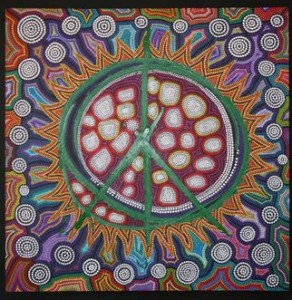

True love…and peace.

October 5, 2020Now, more than ever, peace, peace,

P

E

A

C

E

-Cathie Caccia

Buddhist Monk, Thích Nhất Hạnh, celebrates his 94th birthday on October 11th. It is reported today that he has stopped eating, and very frail.

The Plum Village Monastery in Southern France is sharing that, in his spirit and life, there is hope the next Buddha will not be only embodied into an individual, but into the sangha…community.

In true dialogue, both sides are willing to change. -Thích Nhất Hạnh

“The source of love is deep in us and we can help others realize a lot of happiness. One word, one action, one thought can reduce another person’s suffering and bring that person joy.”

May your transition be peaceful and calm, surrounded by love and grace. -dayle

In the 1960s, Thích Nhất Hạnh played an active role promoting peace during the years of war in Vietnam. ... During his years in the U.S., he met Martin Luther King Jr., who nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967.

What could better look like?

February 20, 2020One thing leads to another.

-Judge J. Edward Lumbard

❦

America is not some finished work or failed project but an ongoing experiment.

If parts of the machine are broken, then the responsibility of citizens is to fix the machine, not throw it away.

Our imperfections can, and out to, draw us together in humility, realism, patience, and determination.

No one has a monopoly on wisdom or is free from error. Everyone benefits from understanding other points of view.

The foundational virtue of democracy is trust, not trust in one’s own rectitude or opinion, but rust in the capacity of collective deliberation to move us forward.

To often we define our real national challenges–climate change, immigration, health care, guns–in a way that guarantees division into warring camps.

Instead we should be asking one another: What could “better” look like?

Our Founders thought in centuries.

Abraham Lincoln warned that the greater danger to the nation came from within. All the armies of the world could not crush us, he maintained, but we could still “die by suicide.”

-James Mattis, a former secretary of defense who served for more than four decades as a Marine infantry officer.

George Washington:

“Sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.”

If we want our democracy to succeed, indeed, if we want the idea of democracy to regain respect in an age when dissatisfaction with democracies is rising, we’ll need to understand the many ways in which today’s [various] platforms create conditions that may be hostile to democracy’s success. And then we’ll have to take decisive action to improve.

-Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and technoethicist Tobias Rose-Stockwell

Bowe.

December 15, 2019“American Cipher: Bowe Bergdahl”

Season 2019 Episode 10 | 28m 47s

Marcia Franklin talks with Michael Ames about his book, “American Cipher: Bowe Bergdahl and the U.S. Tragedy in Afghanistan.” Bergdahl was a soldier from Hailey, Idaho, who walked off his base in Afghanistan in 2009 and was captured by the Taliban. He was held and tortured for five years. Ames and his co-author delve into Bergdahl’s childhood and the politics surrounding the search for him.

[Aired on Dec. 13, 2019

https://video.idahoptv.org/video/american-cipher-bowe-bergdahl-aed8vg/

AT WAR WITH THE TRUTH

U.S. officials constantly said they were making progress. They were not, and they knew it, an exclusive Post investigation found.

The Afghanistan papers

The Secret History of the War

“We were devoid of a fundamental understanding of Afghanistan–we didn’t know what we were doing.” Douglas Lute, a three-star Army general who served as the White House’s Afghan war czar during the Bush and Obama administrations, told government interviewers in 2015. He added: “What are trying to do here? We didn’t have the foggiest notion of what we were undertaking.”

With most speaking on the assumption that their remarks would not become public, U.S. officials acknowledged that their warfighting strategies were fatally flawed and that Washington wasted enormous sums of money trying to remake Afghanistan into a modern nation.

The interviews also highlight the U.S. government’s botched attempts to curtail runaway corruption, build a competent Afghan army and police force, and put a dent in Afghanistan’s thriving opium trade.

The U.S. government has not carried out a comprehensive accounting of how much ithas spent on the war in Afghanistan, but the costs are staggering.

Three Times Listen

January 23, 2018‘If you want to be truly understood, you need to say everything three times, in three different ways. Once for each ear…and once for the heart.’

-Paula Underwood Spencer

☾

‘I’ve learned that true dialogue requires both speaker and listener to try several times to get at what matters. So much depends on timing, and so, I’ve learned not to repeat myself, but to play what matters like a timeless melody, again and again, if the one before me is honest and sincere.’

-Mark Nepo

On Dialogue

February 24, 2017[Ralph Steadman art]

In spite of this worldwide system of linkages, there is, at this very moment, a general feeling that communication is breaking down everywhere, on an unparalleled scale…what appears [in the media] is generally at best a collection of trivial and almost unrelated fragments, while at worst, it can often be a really harmful source of confusion and misinformation.

He terms this “the problem of communication” and writes:

Different groups … are not actually able to listen to each other. As a result, the very attempt to improve communication leads frequently to yet more confusion, and the consequent sense of frustration inclines people ever further toward aggression a and violence, rather than toward mutual understanding and trust.

More from Maria Papova/brainpickings and David Bohm:

“It is clear that if we are to live in harmony with ourselves and with nature, we need to be able to communicate freely in a creative movement in which no one permanently holds to or otherwise defends his own ideas.

Language is collective. Most of our basic assumptions come from our society, including all our assumptions about how society works, about what sort of person we are supposed to be, and about relationships, institutions, and so on. Therefore we need to pay attention to thought both individually and collectively.

“Dialogue” comes from the Greek word dialogos. Logos means “the word,” or in our case we would think of the “meaning of the word.” And dia means “through” — it doesn’t mean “two.” A dialogue can be among any number of people, not just two. Even one person can have a sense of dialogue within himself, if the spirit of the dialogue is present. The picture or image that this derivation suggests is of a stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us. This will make possible a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which may emerge some new understanding. It’s something new, which may not have been in the starting point at all. It’s something creative. And this shared meaning is the “glue” or “cement” that holds people and societies together.

Contrast this with the word “discussion,” which has the same root as “percussion” and “concussion.” It really means to break things up. It emphasizes the idea of analysis, where there may be many points of view, and where everybody is presenting a different one — analyzing and breaking up. That obviously has its value, but it is limited, and it will not get us very far beyond our various points of view. Discussion is almost like a ping-pong game, where people are batting the ideas back and forth and the object of the game is to win or to get points for yourself…

In a dialogue, however, nobody is trying to win. Everybody wins if anybody wins. There is a different sort of spirit to it. In a dialogue, there is no attempt to gain points, or to make your particular view prevail. Rather, whenever any mistake is discovered on the part of anybody, everybody gains. It’s a situation called win-win, whereas the other game is win-lose — if I win, you lose. But a dialogue is something more of a common participation, in which we are not playing a game against each other, but with each other. In a dialogue, everybody wins.”

Exploring reality through narrative.

July 6, 2016(Artist: Marie Stewart, Sun Valley, Idaho)

‘… within (our) narrative, we act in a way that seems reasonable.

To be clear, the narrative isn’t true. It’s merely our version, our self-talk about what’s going on. It’s the excuses, perceptions and history we’ve woven together to get through the world. It’s our grievances and our perception of privilege, our grudges and our loves.

No one is unreasonable. Or to be more accurate, no one thinks that they are being unreasonable.

That’s why we almost never respond well when someone points out how unreasonable we’re being. We don’t see it, because our narrative of the world around us won’t allow us to. Our worldview makes it really difficult to be empathetic, because seeing the world through the eyes of someone else takes so much effort.

It’s certainly possible to change someone’s narrative, but it takes time and patience and leverage. Teaching a new narrative is hard work, essential work, but something that is difficult to do at scale.

In the short run, our ability to treat different people differently means that we can seek out people who have a narrative that causes them to engage with us in reasonable ways. When we open the door for these folks, we’re far more likely to create the impact that we seek. No one thinks they’re unreasonable, but you certainly don’t have to work with the people who are.

And, if you’re someone who finds that your narrative isn’t helping you make the impact you seek, best to look hard at your narrative, the way you justify your unreasonableness, not the world outside.

-Seth Godin

Would you rather…

March 18, 2016Seth Godin:

‘Spend an hour with a good friend in intimate conversation.

spend an hour engaging with your team on the next significant leap in your strategy,

or spend an hour with your smart phone, grooming your social media presence and your inbox?

Good news, you can.’