David Wallace-Wells

Final days. #2022

December 30, 2021‘I regret nothing.’ -Edith Piaf

‘I’ve learned a great deal this year. What kind of year did you have? No matter how many challenges you’ve had, no matter what pain you’ve endured, did you do your very best? Then have no regrets.’ -A. Stoddard

As a collective we should have so many, and we can do so much better. We must. -dayle

Brian McLaren from the Center of Action and Contemplation:

“Something beautiful lies ‘unveiled’ on the other side of complexity and perplexity.”

Gatekeepers have long built razor-wire fences around us with

- beliefs

- rules

- policies

- controversies

- budgets

- programs

- activities

- rituals

- offerings

- inquisitions

Spirituality, though, is available to everyone, like wind, rain, and sun. [Brian McLaren] This is what we harness and share, and protect. “In politics, we’ve been studying war for centuries. We must now study how to crate the conditions for deep and lasting peace. We must now cherish life on earth and engage with it by focusing our best energies on learning to love neighbor, self, earth, and God…Gaia…who is Love.”

LATimes

What LA astronomers and diviners have in store for you in 2022.

-Deborah Netburn, staff writer

‘Spend time dreaming about the world in which you want to live…get specific about what real-life steps you can take to make it a reality. Ask, what does it mean to you to release the Earth, working with others to help the land rest more?’

Full piece [paywall]:

‘These are scary, uncertain times. The pandemic has thrown our lives into chaos once again. Global warming has upended the predictable flow of the seasons. The political climate is divisive and volatile. With all this anxiety swirling around us, is it any wonder that tarot readers, astrologers and other divinatory practitioners say they’ve never been busier? All of us want to know what will happen next.

From the Oracle at Delphi to the Yoruba practitioners of Ifá, there are myriad ways to approach divination and myriad reasons for wanting to see into the future. These tools can be seen as a framework to make sense of the events in our lives. Through this lens, divinatory practices encourage believers to pay attention to the patterns in their lives and the cycles of nature and to move through time with intention.

Los Angeles is among the most spiritually diverse cities in the world; we live alongside thousands of divinatory practitioners from a wide range of traditions — many of whom have devoted their lives to the study of ancient practices that go back thousands of years. As we enter a new calendar year, I asked a handful of them what archetypal energies they expect we’ll encounter over the next 12 months and how we might prepare.’

[Posted on twitter, as seen outside a pub in Europe.]

Eric Holthaus, The Phoenix:

“Any time a climate movie breaks through, it’s worthy of celebration. But this isn’t an ordinary climate movie. #DontLookUp![]() is special.”

is special.”

In the last days of 2021, a year in which Texas froze and the freakin’ ocean caught fire, the number one movie in the world on Netflix is a star-studded climate movie that’s not about climate.

Let me be super clear: Any time climate breaks through, it’s worthy of celebration. But this isn’t an ordinary climate movie. Don’t Look Up is special.

Watching it last night for the first time, I was legitimately blown away by how much I felt like I could relate to the main plot — well-meaning scientists being ignored because their message wasn’t pleasant or profitable. I was scared to watch it because I was worried it would make me feel even more depressed than I already do about being a climate communicator during these decades of climate delay, but it’s just the opposite. This is the climate movie I was waiting for.

“The reason I think Don’t Look Up works so well is because the film’s creators did their homework. There are so many Easter Eggs thrown in throughout that it’s like a love letter to climate activists. There is a massive, waiting audience for authentic climate movies like this that speak to the deep, existential anxiety of being alive at this profoundly terrifying moment in history. We know how to solve the climate emergency — stop burning fossil fuels, build up a circular, caring society, and shift political power so that nothing like it ever happens again — and yet our leaders are staring us straight in the face and saying no.

Director Adam McKay wrote that his own climate anxiety after reading David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth helped inspire the film, and screenplay co-writer David Sirota wrote that empowering the climate movement was a primary goal of the film.

I reached out to McKay and Sirota, and they both confirmed this hunch I had that the movie wasn’t just a political satire, it was a gift for battle-weary activists after several long, hard years of struggle. “We literally made Don’t Look Up for the climate community,” McKay told me.

When I asked Sirota about the movie’s lack of a preachy, prescriptive call-to-action takeaways at the end, he said that was intentional.

“We want it to be a clarion call for the movement,” Sirota said, “But also respect that the movement should decide its tactics.”

The movie isn’t perfect. There’s too much of a focus on the United States, and there’s a valid criticism that seeking action from corrupt politicians during a time of crisis is counterproductive. We know that climate action at the scale and scope we need will only come from collective movements.

But that’s exactly our job now — tell more climate stories that build on this one.

This isn’t a movie that could exist without the decades of failures that have happened so far. But it’s also a movie that finally FINALLY acknowledges that the lynchpin to taking action on climate isn’t about data or carbon or graphs, it’s about finding our shared humanity.

That part is working:

Authentic climate action is way easier than shooting nukes at a comet — it’s treating each other and the Earth better. It’s listening. It’s building systems of power to replace the systems that have been built to kill us.

It’s up to us, the climate movement, to redirect the energy that Don’t Look Up gives us.”

David Wallace-Wells:

“Globally, 250 million people live within three feet of high tide lines. Ten feet of sea level rise would be a world-bending catastrophe. It’s not only goodbye Miami, but goodbye to virtually every low-lying coastal city in the world.”

“Thwaites Glacier is the size of Florida. It is the cork in the bottle of the entire West Antarctic ice sheet, which contains enough ice to raise sea levels by 10 feet.” The great Jeff Goodell on the scary signs from the “Doomsday” glacier.

Rolling Stone

by Jeff Goodall

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/doomsday-glacier-thwaites-antarctica-climate-crisis-1273841/

New data suggests a massive collapse of the ice shelf in as little as five years. “We are dealing with an event that no human has ever witnessed,” says one scientist. “We have no analog for this”

“Given the ongoing war for American democracy and the deadly toll of the Covid pandemic, the loss of an ice shelf on a far-away continent populated by penguins might not seem to be big news. But in fact, the West Antarctic ice sheet is one of the most important tipping points in the Earth’s climate system. If Thwaites Glacier collapses, it opens the door for the rest of the West Antarctic ice sheet to slide into the sea. Globally, 250 million people live within three feet of high tide lines. Ten feet of sea level rise would be a world-bending catastrophe. It’s not only goodbye Miami, but goodbye to virtually every low-lying coastal city in the world.”

Power in disorder (Joan Didion). Let’s reclaim it now.

Order, disorder, reorder (Father Richard Rohr).

Pandemic life.

Climate Emergency.

Pari Center, Italy.

#MustRead

April 28, 2020Two thorough reports regarding current COVID research.

- ProPublica: ‘What Antibody Studies Can Tell You – and More Importantly, What They Can’t’, by Caroline Chen

- New York Magazine: ‘We Still Don’t Know How the Coronavirus Is Killing Us’, by David Wallace-Wells

Caroline Chen:

‘Bear with me here as we wade through some jargon, because I think it’s worth your time. So far, the death rates you’ve seen in headlines have largely been casefatality rates, which are the number of deaths reported divided by the number of cases confirmed with a diagnostic test. That’s all we’ve been able to report so far. You should expect the case fatality rate to be higher than the infectionfatality rate, because there are way more people infected than people who have been able to be tested. We’ll get back to what we’re learning about the infection fatality rate in available studies later on, but for now, just know that this is one reason why sero-surveys are so useful to us.

But there’s more you can learn from a sero-survey. Dan Larremore, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, whose recent work has focused on designing antibody surveys, said you can use sero-surveys to find out if there are certain neighborhoods that have been harder hit than others. Or, by surveying specific populations, you can study questions like: “How much transmission is there within a household?” or “What’s the role of kids in all of this?”

To do that properly, researchers need to test a random sample of the population.

The ideal way to conduct a sero-survey, according to Natalie Dean, assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Florida, would be to randomly select addresses from a database of the population you want to survey and then send a team of researchers door to door to collect samples. The World Health Organization’s guidance for such studies recommends inviting all people who live in the household to participate in the study, including children.

In order to achieve herd immunity, scientists say that a community would need to have at least 60% of its population infected. That’s the lowest estimate I’ve been told. Other scientists have told me 80% to 90%. The reason this percentage isn’t precisely known is because it depends on things like exactly how contagious the virus is and also whether people who have been infected are immune forever, or if they lose immunity after a while, which researchers also are furiously working to figure out.

As antibody tests become more widely available, there’ll naturally be a temptation to start using the tests for ourselves on an individual basis, to determine if we’re immune and can go about our lives, free of the paranoia and fear that have been plaguing us for the past two months.

But it’s too early for that.

Besides the issue of potential false positives, scientists haven’t yet figured out exactly what level of protection an individual has after being infected and whether the protection lasts forever (like with chickenpox) or wanes after a while. The World Health Organization issued a scientific brief last week warning that detection of antibodies alone shouldn’t serve as a basis for an “immunity passport” allowing an individual to assume they are totally protected from reinfection.

David Wallace-Wells:

‘The disease itself appears to be shape-shifting before our eyes.

“Despite the relentless, heroic work of doctors and scientists around the world. There’s so much we don’t know.”

One month ago, as the country went into lockdown to prepare for the first wave of coronavirus cases, many doctors felt confident that they knew what they were dealing with. Based on early reports, covid-19 appeared to be a standard variety respiratory virus, albeit a very contagious and lethal one with no vaccine and no treatment. But they’ve since become increasingly convinced that covid-19 attacks not only the lungs, but also the kidneys, heart, intestines, liver and brain.

t’s not unheard of, of course, for a disease to express itself in complicated or hard-to-parse ways, attacking or undermining the functioning of a variety of organs. And it’s common, as researchers and doctors scramble to map the shape of a new disease, for their understanding to evolve quite quickly. But the degree to which doctors and scientists are, still, feeling their way, as though blindfolded, toward a true picture of the disease cautions against any sense that things have stabilized, given that our knowledge of the disease hasn’t even stabilized. Perhaps more importantly, it’s a reminder that the coronavirus pandemic is not just a public-health crisis but a scientific one as well. And that as deep as it may feel we are into the coronavirus, with tens of thousands dead and literally billions in precautionary lockdown, we are still in the very early stages, when each new finding seems as likely to cloud or complicate our understanding of the coronavirus as it is to clarify it. Instead, confidence gives way to uncertainty.

In the space of a few months, we’ve gone from thinking there was no “asymptomatic transmission” to believing it accounts for perhaps half or more of all cases, from thinking the young were invulnerable to thinking they were just somewhat less vulnerable, from believing masks were unnecessary to requiring their use at all times outside the house, from panicking about ventilator shortages. Six months since patient zero, we still have no drugs proven to even help treat the disease. Almost certainly, we are past the “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” stage of this pandemic, but how far past?

https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/04/we-still-dont-know-how-the-coronavirus-is-killing-us.html

“We have to cool the planet.”

June 20, 2019David Wallace-Wells, Author of the book, The Uninhabitable Earth/Life After Warming [‘The most terrifying book I have ever read.’ -Farhad Manjoo, The New York Times]

“It’s become fashionable to call for a WWII-style climate mobilization. But virtually no one will call for activities the U.S. actually undertook then—rationing food and fuels, seizing property, nationalizing factories or industries, suspending liberties.”

David Wallace-Wells

https://issues.org/the-empty-radicalism-of-the-climate-apocalypse/

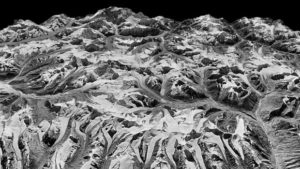

Himalayan glacier melting doubled since 2000, spy satellites show

Ice losses indicate ‘devastating’ future for region and 1 billion people who depend on it for water

The Guardian

The analysis shows that 8bn tonnes of ice are being lost every year and not replaced by snow, with the lower level glaciers shrinking in height by 5 meters annually. The study shows that only global heating caused by human activities can explain the heavy melting. In previous work, local weather and the impact of air pollution had complicated the picture.

Joshua Maurer, from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth observatory, who led the new research, said: “This is the clearest picture yet of how fast Himalayan glaciers are melting since 1975, and why.” The research is published in the journal Science Advances.

[…]

The spy satellite photographs used in the research had lain unused in archives for some years. But a computer tool developed by Maurer and colleagues enabled these 1970s photos to be turned into 3D maps.

Schaefer said: “For the wellbeing of the people there, our results are of course the worst possible. But it is what it is, and now we have to prepare for that scenario. We have to worry a lot, because so many people are affected.

“To stop the temperature rises, we have to cool the planet,” he said. “We have to not only slow down greenhouse gas emissions, we have to reverse them. That is the challenge for the next 20 years.”

“Is it too late for us? Scientists have spent decades sounding the alarm on the devastating effects of climate change. And for decades, society decided to do pretty much nothing about it. In fact, over the past 30 years, we’ve done more damage to the climate than in all of human history! Now, there’s a real chance we may have waited too long to avoid widespread tragedy and suffering. In his book “The Uninhabitable Earth”, David Wallace-Wells depicts a catastrophic future far worse than we ever imagined…and far sooner than we thought. It is undoubtedly a brutal truth to face, as you will hear in this episode, but if there’s any hope to avert the worst case scenarios, we have to start now.”

[First aired in March 2019]

https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/msnbc/why-is-this-happening/e/59220213

“…surely not alarmed enough.”

February 11, 2018“Complacency is much more dangerous than fatalism.’

New York Magazine:

There’s a lot of scientific debate about the future of climate change. But have you ever considered the worst case scenario? David Wallace-Wells gives us one terrifying glimpse into the future after consulting experts from various fields.

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2017/07/climate-change-earth-too-hot-for-humans.html

But no matter how well-informed you are, you are surely not alarmed enough. Over the past decades, our culture has gone apocalyptic with zombie movies and Mad Max dystopias, perhaps the collective result of displaced climate anxiety, and yet when it comes to contemplating real-world warming dangers, we suffer from an incredible failure of imagination. The reasons for that are many: the timid language of scientific probabilities, which the climatologist James Hansen once called “scientific reticence” in a paper chastising scientists for editing their own observations so conscientiously that they failed to communicate how dire the threat really was; the fact that the country is dominated by a group of technocrats who believe any problem can be solved and an opposing culture that doesn’t even see warming as a problem worth addressing; the way that climate denialism has made scientists even more cautious in offering speculative warnings; the simple speed of change and, also, its slowness, such that we are only seeing effects now of warming from decades past; our uncertainty about uncertainty, which the climate writer Naomi Oreskes in particular has suggested stops us from preparing as though anything worse than a median outcome were even possible; the way we assume climate change will hit hardest elsewhere, not everywhere; the smallness (two degrees) and largeness (1.8 trillion tons) and abstractness (400 parts per million) of the numbers; the discomfort of considering a problem that is very difficult, if not impossible, to solve; the altogether incomprehensible scale of that problem, which amounts to the prospect of our own annihilation; simple fear. But aversion arising from fear is a form of denial, too.

To The Best of Our Knowledge:

There’s a lot of scientific debate about the future of climate change. But have you ever considered the worst case scenario? David Wallace-Wells gives us one terrifying glimpse into the future after consulting experts from various fields.

https://www.ttbook.org/interview/how-bad-can-climate-change-really-get

And while many people are working to try to counter this imbalance, most are approaching it with the very same mind-set that has created this predicament. Before we can begin to redeem this crisis, we need to go to the root of our present paradigm—our sense of separation from our environment, the lack of awareness that we are all a part of one interdependent living organism that is our planet. This can be traced to the birth of the scientific era in the Age of Enlightenment and the emergence of Newtonian physics, in which humans were seen as separate from the physical world, which in turn was considered as unfeeling matter, a clockwork mechanism whose workings it was our right and duty to understand and control.

While this attitude has given us the developments of science and technology, it has severed us from any relationship to the environment as a living whole of whose cycles we are a part. We have lost and entirely forgotten any spiritual relationship to life and the planet, a central reality to other cultures for millennia.1 Where for indigenous peoples the world was a sacred, interconnected living whole that cares for us and for which we in turn need to care—our Mother the Earth—for our Western culture it became something to exploit.

But there is an even deeper, and somewhat darker, side to our forgetfulness of the sacred within creation. When our monotheistic religions placed God in heaven they banished the many gods and goddesses of the Earth, of its rivers and mountains. We forgot the ancient wisdom contained in our understanding of the sacred in creation—its rhythms, its meaningful magic. For example, when early Christianity banished paganism and cut down its sacred groves, they forgot about nature devas, the powerful spirits and entities within nature, who understand the deeper patterns and properties of the natural world. Now how can we even begin the work of healing the natural world, of clearing out its toxins and pollutants, of bringing it back into balance, if we do not consciously work with these forces within nature?

Nature is not unfeeling matter; it is full of invisible forces with their own intelligence and deep knowing. We need to reacknowledge the existence of the spiritual world within creation if we are even to begin the real work of bringing the world back into balance. Only then can we regain the wisdom of the shamans who understood how to communicate and work together with the spirit world.2

While there may be a growing awareness that the world forms a single living being—what has been called the Gaia principle—we don’t really understand that this being is also nourished by its soul, the anima mundi—or that we are a part of it, part of a much larger living, sacred being. Sadly, we remain cut off, isolated from this spiritual dimension of life itself. We have forgotten how to nourish or be nourished by the soul of the world….3

We cannot return to the simplicity of an indigenous lifestyle, but we can become aware that what we do and how we are at an individual level affects the global environment, both outer and inner. We can learn how to live in a more sustainable way, not to be drawn into unnecessary materialism.

We can also work to heal the spiritual imbalance in the world. Our individual conscious awareness of the sacred within creation reconnects the split between spirit and matter within our own soul and also within the soul of the world: we are part of the spiritual body of the Earth more than we know.

The crisis we face now is dire, but it is also an opportunity for humanity to reclaim its role as guardian of the planet, to take responsibility for the wonder and mystery of this living, sacred world.

Full article:

https://parabola.org/2018/01/10/the-call-of-the-earth-by-llewellyn-vaughan-lee/

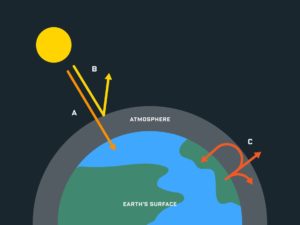

THE WIRED GUIDE TO CLIMATE CHANGE

How this Global Climate Shift Got Started

“If we want to go all the way back to the beginning, we could take you to the Industrial Revolution—the point after which climate scientists start to see a global shift in temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. In the late 1700s, as coal-fired factories started churning out steel and textiles, the United States and other developed nations began pumping out its byproducts. Coal is a carbon-rich fuel, so when it combusts with oxygen, it produces heat along with another byproduct: carbon dioxide. Other carbon-based fuels, like natural gas, do the same in different proportions.

When those emissions entered the atmosphere, they acted like an insulating blanket, preventing the sun’s heat from escaping into space. Over the course of history, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have varied—a lot.”