Civil Eats

#NativeAmericanHeritageDay

November 26, 2021“Native Americans are the keepers of traditions and defenders of our natural resources. This Native American Heritage Day, I honor our culture and our ancestors. At the Interior, we will continue to include Indigenous knowledge as we protect our lands for future generations.”

-Secretary Deb Haaland, 54th Secretary of the Interior, 35th generation New Mexican, Pueblo of Laguna Tribe

[Image: Lakota Man/Twitter]

‘That’s what gods do, they spin threads of ruin through the fabric of our lives, all to make songs for generations to come.’ -Anthony Doerr ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land’, p.439

Post

C

o

l

o

n

i

a

l

Stress

D

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

PCSD

“We’re still in the genocide. It’s still happening; we’re still doing it.”

Why?

We need to look at our “individual power in relation to the world.” -Rose

Rilke: “…blessed our those who stood quietly in the rain. Theirs shall be the harvest; for them the fruits. They will outlast pomp and power, whose meaning and structures will crumble. When all else is exhausted and bled of purpose, they will lift their hands, they have survived.”

Mixed-media artist Rose B. Simpson lives and works from her home at Santa Clara Pueblo in New Mexico.

(This piece was commissioned for the the Conspire conference, Center for Action and Contemplation, in New Mexico.)

https://www.rosebsimpson.com/about

[Rose B. Simpson, Holding it Together (detail), 2016, sculpture]

Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ

All our relations

The Last Archive

Jill Lepore, historian and Harvard professor

“Indigenous paradigm, a paradigm about relationships–all things are kin, rocks the skies, trees, family…”

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-last-archive/id1506207997?i=1000540005084

LATIMES

“The Indigenous Serrano Language Was All But Gone, This Man is Resurrecting It.”

When Ernest Siva was a boy on the Morongo Reservation in Riverside County, he listened to the music and stories of his ancestors, who had lived in Southern California long before the land was called by that name.

He recalls running around a ceremonial fire on the reservation at age 5 as a weeklong ceremony honoring those who had died the previous year culminated with the burning of images in their likeness. Dollar bills and coins were thrown into the fire in tribute as tribal elders sang songs reserved for special occasions. Siva and his cousin chased after the singed money that fluttered out of the flames, largely ignoring the traditional lyrics in the background.

The specific words and rhythms are now distant memories for the 84-year-old Siva, a Cahuilla/Serrano Native American.

Siva is working to change that. For the last 25 years, the Banning resident has been a tribal historian with the Morongo Band of Mission Indians.

CIVIL EATS

In the face of climate change and persistent droughts, a growing number of people from Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico and elsewhere are adopting the traditional farming practice.

Historic Zuni waffle gardens, circa 1919. (Photo courtesy of Kirk Bemis)

“It’s going to be difficult, but in the meantime, we still have to do what we can to find ways to adapt and live with it. And I think that the waffle gardens are one tool for us to make it through.”

(The) hope is for every household within the Zuni village to have a backyard garden, and that such a shift could cut a family’s need to shop for groceries in half.

“A small, 4-by-8 [foot] garden will get you a good four to five buckets full of corn, which is not enough to completely live off, but enough to feed our families, survive, and carry out our traditions.” He also thinks it’s important for the Zuni people to lessen dependence on grocery stores, which the pandemic showed are vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

https://civileats.com/2021/10/26/resurgence-waffle-gardens-helping-indigenous-peoples-thrive-amid-droughts-grow-food-less-water/

Maria Popova

The Marginalian

“Ever since we climbed down from the trees, we have been looking up to them to understand ourselves and our place in the universe. “Nothing is holier, nothing is more exemplary than a beautiful, strong tree,” Hermann Hesse wrote a century ago in his sublime sylvan love letter, affirming that “when we have learned how to listen to trees, then the brevity and the quickness and the childlike hastiness of our thoughts achieve an incomparable joy.”

Centuries, millennia before Hesse — before Wangari Maathai won the Nobel Prize for her courageously enacted conviction that “a tree is a little bit of the future,” before scientists uncovered the astonishing language of trees, before Western artists saw in tree silhouettes a Rorschach test for what we are — the indigenous artists and storytellers of the Gond tribe in central India have been reverencing the secret lives of trees as portals into the inner life of nature, into the wildness of our own nature, into a supra-natural universe of myth and magic.”

The Secret Life of Trees: Stunning Sylvan Drawings by Indigenous Artists Based on Indian Mythology

Civil Eats

June 13, 2019How an Oregon Rancher is Building Soil Health—and a Robust Regional Food System

Fourth-generation rancher Cory Carman holistically manages 5,000-acres which serve as a model for sustainable meat operations in the Pacific Northwest.

Carman Ranch began as a few hundred acres Carman’s great-great-grandfather Jacob Weinhard—nephew to the legendary Northwest beer brewer Henry Weinhard—bought for his son Fritz in the early 1900s. Under Carman’s watch, the operation now spans 5,000 acres of grasslands, timbered rangeland, and irrigated valley ground nestled against the dramatic peaks of the Wallowa Mountains. Hawks, eagles, and wildlife greatly outnumber people in this isolated northeastern corner of the state, originally home to the Wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of the Nez Perce tribe.

Distinct from most cattle operations in the U.S., Carman’s cattle are 100 percent grass-fed well as grass-finished. (The term “grass-fed” is not regulated, so it can mean that animals have only been briefly pastured before they’re sent to a factory feedlot to be finished.) The ranch primarily produces cattle and pigs, which it mostly markets to wholesale accounts, though it sells a lesser amount of meat as “cow shares”—or quarters of beef ranging from 120 to 180 pounds purchased directly by consumers.

Equally if not more important to Carman, however, is the focus on what she calls the “holistic management” of her land. This involves constantly moving the cattle and paying careful attention to the rate of growth of the animals and grasses. By this system, the steers select the forages they need to grow and gain weight, and the grasses get clipped, trampled down, and fertilized with manure, resulting in fields that are vibrant—they retain water, resist drought, contain abundant organic matter, which contributes nutrients and carbon, and are highly productive without the addition of fertilizer.

https://civileats.com/2019/01/31/how-an-oregon-rancher-is-building-soil-health-and-a-robust-regional-food-system/

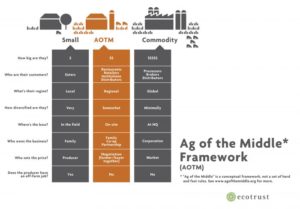

Mid-Sized Farms Are Disappearing. This Program Could Reverse the Trend.

A new ‘Ag of the Middle’ program helps small producers scale up so that they can compete in a food system designed to benefit larger farms.

“If we don’t invest in beginning farmers and the advancement of our family farms, and if we don’t put checks on increasing consolidation in agriculture, we’re going to be at risk of losing the ag of the middle entirely,” said Juli Obudzinski, National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition Interim Policy Director, in a recent statement. “Seventy-five percent of all agricultural sales are now coming from just 5 percent of operations.”

Over the years, a number of experts have written books and formed think tanks to address agriculture’s shrinking middle, but as many of the men and women running the remaining mid-sized farms are looking toward retirement, the most important question may be how to best help farmers like the Menchinis grow to take their place.

The Ag of the Middle Accelerator Program from Portland-based nonprofit Ecotrust aims to do just that. The two-year program helps smaller farms, ranches, and fishermen grow to gross between $100,000 to $3 million. And it hopes to build a model that can be borrowed and reproduced all around the country.

Expanding The Shrinking Middle

While there are no hard and fast rules dictating farm size, mid-size operations tend to be regional, somewhat diverse operations that negotiate prices with their customers in restaurant, retail, or at institutions, while large farms are typically less diverse, operate globally, and make millions selling to processors, brokers, or distributors for a price that is set by the market.

https://civileats.com/2019/06/11/mid-sized-farms-are-disappearing-this-program-could-reverse-the-trend/

$1 billion per page.

January 9, 2019“On December 20, DT signed the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (commonly knows as the Farm Bill) into law. The bill, projected to cost $28 billion over the next five years, is one of the largest spending packages in the country, doling out money for low-income nutrition assistance, crop insurance, commodity subsidies and conservation programs, among other things. Learn more about the triumphs and failures of the new farm bill from Marion Nestle on Food Politics and Dan Imhoff on Civil Eats.” -Local Food Alliance

The bill takes up 807 pages, with a table of contents of 11 pages. It will cost taxpayers $867 billion over ten years. That’s more than $1 billion per page.

by Marion Nestle

SNAP

Recall that more than 75% of Farm Bill expenditures go for SNAP—The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly Food Stamps).

The “bipartisan win”? Attempts to cut SNAP expenditures and introduce work requirements failed to pass (whew), although Congress is still working on ways to cut enrollments.

Commodity payments

The bill allows payments to more distant relatives of farm owners—cousins, nieces, nephews—a gift to the already rich. Payments can still go to those earning more than $900,000 a year in adjusted gross income (sigh).

Organics

The bill authorizes $395 million in research funding over the next 10 years, and small amounts for data collection, offset of certification costs, and technology upgrades. But the bill weakens restrictions on chemicals that can be used in organic production.

Hemp

The bill grants $2 million a year for support of hemp as a crop, and authorizes USDA to study the economic viability of its domestic production and sale. It also authorizes Indian tribes (that’s the term the bill uses) to grow hemp.

Cuba

The bill allows funding for USDA trade promotion programs in Cuba.

The Managers recognize that expanding trade with Cuba not only represents an opportunity for American farmers and ranchers, but also a chance to improve engagement with the Cuban people in support of democratic ideas and human rights…The Managers expect that the Secretary will work closely with eligible trade organizations to educate them about allowable activities to improve exports to Cuba under the Market Access and Foreign Market Development Cooperator Programs.

https://www.foodpolitics.com/2018/12/the-2018-farm-bill-more-of-the-same-old-same-old/

https://civileats.com/2018/12/13/despite-small-wins-the-new-farm-bill-is-a-failure-of-imagination/

JOIN THE GRANGE

Founded in 1924, Upper Big Wood River Grange, aka the Hailey Grange, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, fraternal organization that advocates for rural America and agriculture. It also is home to the Wood River Seed Library’s Seed Vault. Learn about becoming a member at the Grange’s January 17 Meeting and Annual New Member Drive – 7:15-8:45pm, at Grange Hall, 609 South 3rd Ave. in Hailey. Guest speaker Aimée Christensen, founder and executive director of Sun Valley Institute, will talk about resiliency and food-related risks and opportunities before us.