Racial Privilege and Chords of Memory

Isabel Wilkerson’s follow-up to The Warmth of Other Suns will be released on August 20th.

She wrote an essay on July 1st for the New York Times called,

America’s Enduring Caste System

Our founding ideals promise liberty and equality for all. Our reality is an enduring racial hierarchy that has persisted for centuries.

[link]

“[Caste] should be at the top of every American’s reading list.”—Chicago Tribune

“As we go about our daily lives, caste is the wordless usher in a darkened theater, flashlight cast down in the aisles, guiding us to our assigned seats for a performance. The hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality. It is about power—which groups have it and which do not.”

‘In this brilliant book, Isabel Wilkerson gives us a masterful portrait of an unseen phenomenon in America as she explores, through an immersive, deeply researched narrative and stories about real people, how America today and throughout its history has been shaped by a hidden caste system, a rigid hierarchy of human rankings.

Beyond race, class, or other factors, there is a powerful caste system that influences people’s lives and behavior and the nation’s fate. Linking the caste systems of America, India, and Nazi Germany, Wilkerson explores eight pillars that underlie caste systems across civilizations, including divine will, bloodlines, stigma, and more. Using riveting stories about people—including Martin Luther King, Jr., baseball’s Satchel Paige, a single father and his toddler son, Wilkerson herself, and many others—she shows the ways that the insidious undertow of caste is experienced every day. She documents how the Nazis studied the racial systems in America to plan their out-cast of the Jews; she discusses why the cruel logic of caste requires that there be a bottom rung for those in the middle to measure themselves against; she writes about the surprising health costs of caste, in depression and life expectancy, and the effects of this hierarchy on our culture and politics. Finally, she points forward to ways America can move beyond the artificial and destructive separations of human divisions, toward hope in our common humanity.

Beautifully written, original, and revealing, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents is an eye-opening story of people and history, and a reexamination of what lies under the surface of ordinary lives and of American life today.’ [Amazon]

From writer Eula Biss, posted on Dec. 2, 2015.

White Debt

Reckoning with what is owed–and what can never be repaid–for racial privilege.

[link]

The word for debt in German also means guilt.

Only something that continues to hurt stays in the memory,’’ Nietzsche observes in ‘On the Genealogy of Morality.’

The power to punish, Nietzsche notes, can enhance your sense of social status, increasing the pleasure of cruelty.

“I read several hundred pages of ‘‘Little House on the Prairie’’ to my 5-year-old son one day when he was home sick from school. Near the end of the book, when the Ingalls family is reckoning with the fact that they built their little house illegally on Indian Territory, and just after an alliance between tribes has been broken by a disagreement over whether or not to attack the settlers, Laura watches the Osage abandoning their annual buffalo hunt and leaving Kansas. Her family will leave, too. At this point, my son asked me to stop reading. ‘‘Is it too sad?’’ I asked. ‘‘No,’’ he said, ‘‘I just don’t need to know any more.’’ After a few moments of silence, he added, ‘‘I wish I was French.’’

The Indians in ‘‘Little House’’ are French-speaking, so I understood that my son was saying he wanted to be an Indian. ‘‘I wish all that didn’t happen,’’ he said. And then: ‘‘But I want to stay here, I love this place. I don’t want to leave.’’ He began to cry, and I realized that when I told him ‘‘Little House’’ was about the place where we live, meaning the Midwest, he thought I meant it was about the town where we live and the house we had just bought. Our house is not that little house, but we do live on the wrong side of what used to be an Indian boundary negotiated by a treaty that was undone after the 1830 Indian Removal Act. We live in Evanston, Ill., named after John Evans, who founded the university where I teach and defended the Sand Creek massacre as necessary to the settling of the West. What my son was expressing — that he wants the comfort of what he has but that he is uncomfortable with how he came to have it — is one conundrum of whiteness.

‘‘Tell me again about the liar who lied about a lie,’’ my son said recently. It took me a moment to register that he meant Rachel Dolezal. He had heard me talking about her with Noel Ignatiev, author of ‘‘How the Irish Became White.’’ I had said: ‘‘She might be a liar, but she’s a liar who lied about a lie. The original fraud was not hers.’’ Because I was talking to Noel, who sent me to James Baldwin’s essay ‘‘On Being White … and Other Lies’’ when I was in college, I didn’t have to clarify that the lie I was referring to was the idea that there is any such thing as a Caucasian race. Dolezal’s parents had insisted to reporters that she was ‘‘Caucasian’’ by birth, though she is not from the Caucasus region, which includes contemporary Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. Outside that context, the word ‘‘Caucasian’’ is a flimsy and fairly meaningless product of the 18th-century pseudoscience that helped invent a white race.

Whiteness is not a kinship or a culture. White people are no more closely related to one another, genetically, than we are to black people. American definitions of race allow for a white woman to give birth to black children, which should serve as a reminder that white people are not a family. What binds us is that we share a system of social advantages that can be traced back to the advent of slavery in the colonies that became the United States. ‘‘There is, in fact, no white community,’’ as Baldwin writes. Whiteness is not who you are. Which is why it is entirely possible to despise whiteness without disliking yourself.

When he was 4, my son brought home a library book about the slaves who built the White House. I didn’t tell him that slaves once accounted for more wealth than all the industry in this country combined, or that slaves were, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, ‘‘the down payment’’ on this country’s independence, or that freed slaves became, after the Civil War, ‘‘this country’s second mortgage.’’ Nonetheless, my overview of slavery and Jim Crow left my son worried about what it meant to be white, what legacy he had inherited. ‘‘I don’t want to be on this team,’’ he said, with his head in his hands. ‘‘You might be stuck on this team,’’ I told him, ‘‘but you don’t have to play by its rules.’’

Even as I said this, I knew that he would be encouraged, at every juncture in his life, to believe wholeheartedly in the power of his own hard work and deservedness, to ignore inequity, to accept that his sense of security mattered more than other people’s freedom and to agree, against all evidence, that a system that afforded him better housing, better education, better work and better pay than other people was inherently fair.

My son’s first week in kindergarten was devoted entirely to learning rules. At his school, obedience is rewarded with fake money that can be used, at the end of the week, to buy worthless toys that break immediately. Welcome to capitalism, I thought when I learned of this system, which produced, that week, a yo-yo that remained stuck at the bottom of its string. The principal asked all the parents to submit a signed form acknowledging that they had discussed the Code of Conduct with their children, but I didn’t sign the form. Instead, my son and I discussed the civil rights movement, and I reminded him that not all rules are good rules and that unjust rules must be broken. This was, I now see, a somewhat unhinged response to the first week of kindergarten. I know that schools need rules, and I am a teacher who makes rules, but I still want my son to know the difference between compliance and complicity.”

“…I see what you do.”

Ryan Vizzions, Professional Photographer/Civil & Human Rights:

This photograph got me an FBI file, but it sure did it’s job.

It was Viola Desmond’s turn.

July 6, 2020Viola Desmond took a stand against racism in Nova Scotia in 1946 when she refused to move from a theatre seat that was reserved for white patrons.

Radical Tea Towel

Today, back in 1914, Viola Desmond was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Rarely as explicit as Jim Crow in the US, racism against black citizens in Canada was no less pernicious.

In Nova Scotia, segregation was widespread.

The Roseland Film Theatre in New Glasgow was a case in point.

The better, main floor seats were reserved for white patrons while black customers were confined to the balcony.

In 1943, Carrie Best, a black Nova Scotian, had tried to challenge this set-up without success.

On 8th November 1946, Desmond’s car broke down in New Glasgow and so she went to the Roseland Theater to watch a movie while it was repaired.

Unaware of the segregation – it was unofficial because there were no segregation laws in New Glasgow – Desmond moved down to the main floor where she could see better.

It wasn’t long before she was asked to move by a member of staff.

Viola immediately knew what was going on – she’d faced anti-black racism in Canada ever since being barred from beautician training as a young woman in Halifax.

But on that night in Nova Scotia, she took a stand.

Viola refused to leave her seat until she was forcibly thrown out of the theater, injuring her hip in the process.

She was then arrested and spent the night in jail on the absurd claim of a tax violation.

Back home in Halifax, Desmond was convinced by her Baptist pastor, William Pearly Oliver, to challenge her arrest in court (as in the US, the Baptist Church was at the cent re of black civil rights activism in Canada).

Supported by the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (modelled on the American NAACP) and Carrie Best, who had by now set up a newspaper, The Clarion, to advocate for black Canadians, Viola Desmond took the Roseland Theater to court.

She didn’t win, but that’s not the point.

In the atmosphere of 1946, when many Canadians believed they’d just fought a bitter war to overcome racist Nazism in Europe, Viola Desmond’s act of defiance sparked new life into the Canadian civil rights movement at home.

To some in countries like Canada and England, it’s a tempting delusion to see anti-black racism as a ‘US problem’.

This thinking tries to brush histories of white supremacy under the rug, but it also buries the inspiring stories of anti-racist resistance.

From Viola Desmond in Nova Scotia to the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963, the epic of black power and black liberation extends well beyond the United States.

Black lives matter – all over the world.

Independence. For whom?

July 4, 2020‘The tragedy of nations is perhaps this: that even the best rulers use up a piece of their people’s future.’ –Rilke

All people.

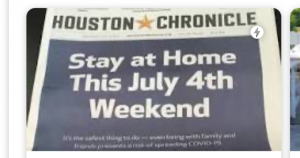

July 3, 20204th of July

‘There is only one true flight from the world: it is not an escape from conflict anguish, and suffering, but the flight from dignity and separation, to unity and peace in the love of other [people].’

-Thomas Merton, Seeds of Contemplation

What Dorothy Day called ‘a revolution of the heart’ is blossoming in our streets, where revolutionaries seem confident America can spend less on war and police, make the 1% and corporations pay their fare share and ensure healthcare, living wages, etc., for all. -Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II

NPR

Frederick Douglass’ Descendants Deliver His ‘Fourth Of July’ Speech

How can you watch and not weep? 4th of July belongs to all of us. It must.

‘In this short film, five young descendants of Frederick Douglass read and respond to excerpts of his famous speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” which asks all of us to consider America’s long history of denying equal rights to Black Americans.’

Douglass Washington Morris II, 20 (he/him) Isidore Dharma Douglass Skinner, 15 (they/their) Zoë Douglass Skinner, 12 (she/her) Alexa Anne Watson, 19 (she/her) Haley Rose Watson, 17 (she/her)

Love will rise above all.

Sun Valley, Idaho.

We speak our hopes.

A rose by itself is every rose.

And this one is irreplaceable,

perfect, one sufficient word

in the context of all things.

Without what we see in her,

how can we speak our hopes

or endure a tender moment

in the winds of departure.

-Rilke

Thoughts.

What does it mean to be good?

What would you die for you?

What mosts interests you? Name three.

•

•

•

What is the last thing you did with your whole ♥

“Now when I am old my teachers are the young.” -Robert Frost