1865. 1920. 1960. 2020.

June 10, 20201865.

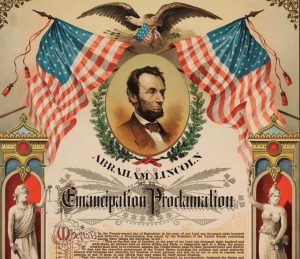

June 19—“Juneteenth,” also called Emancipation Day—commemorates the day in 1865 that the Emancipation Proclamation was read to enslaved African Americans in Texas and is now honored in 47 states.

[Historian Michael Beschloss]

1920.

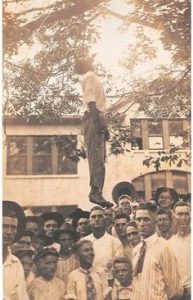

Postcard depicting the lynching of LIGE DANIELS, Center, Texas. August 3, 1920. The back reads, “This was made in the court yard in Center, Texas. He is a 16 year old Black boy.

1960.

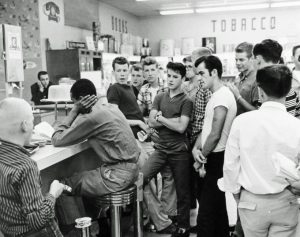

Protester harassed during sit-in at segregated drugstore lunch counter, Arlington, Virginia, 1960.

[Historian Michael Beschloss]

2020.

This still image taken from a May 25, 2020, video courtesy of Darnella Frazier via Facebook, shows a Minneapolis, Minnesota, police officer arresting, and suffocating, George Floyd.

[DARNELLA FRAZIER/FACEBOOK/DARNELLA FRAZIER/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES]

‘Collective anger, anguish, and grief.’

-Trymaine Lee

@trymainelee

Desperately Needed Fundamental Change

“If you want to bring in different perspectives, you’ll have a different culture & different environment that will lead you to make different decisions.”

James Bennet, recently resigned opinion editor for the NYTimes, representing collective White privilege patriarchy…father, Douglas Bennet, former NPR Director/Wesleyan University president and part of both the Carter & Clinton administrations, and brother, Michael Bennet, U.S. Senator and former U.S. Presidential candidate. -dayle

A copy of the December 23, 2018, edition of the New York Times.Robert Alexander/Getty Images

VOX

America is changing, and so is the media

The media has gone through painful periods of change before. But this time is different

By

There have always been boundaries around acceptable discourse, and the media has always been involved, in a complex and often unacknowledged way, in both enforcing and contesting them. In 1986, the media historian Daniel Hallin argued that journalists treat ideas as belonging to three spheres, each of which is governed by different rules of coverage. There’s the “sphere of consensus,” in which agreement is assumed. There’s the “sphere of deviance,” in which a view is considered universally repugnant, and it need not be entertained. And then, in the middle, is the “sphere of legitimate controversy,” wherein journalists are expected to cover all sides, and op-ed pages to represent all points of view.

The media’s week of reckoning

Last week, the New York Times op-ed section solicited and published an article by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) arguing that the US military should be deployed to “restore order to our streets.” The piece set off an internal revolt at the Times, with staffers coordinating pushback across Twitter, and led to the resignation of James Bennet, the editor of the op-ed section, and the reassignment of Jim Dao, the deputy editor.

That same week, Stan Wischnowski, the top editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, resigned after publishing an article by the paper’s architecture critic titled “Buildings Matter, Too.” David Boardman, the chair of the board that controls the Inquirer, said Wischnowski had done “remarkable” work but “leaves behind some decades-old, deep-seated and vitally important issues around diversity, equity and inclusion, issues that were not of his creation but that will likely benefit from a fresh approach.”

One interpretation of these events, favored by frustrated conservatives, is that a generation of young, woke journalists want to see the media remade along activist lines, while an older generation believes it must cover the news without fear and favor, and reflect, at the very least, the full range of views held by those in power.

“The New York Times motto is ‘all the news that’s fit to print,’” wrote the Times’s Bari Weiss. “One group emphasizes the word ‘all.’ The other, the word ‘fit.’”

Another interpretation is that the range of acceptable views isn’t narrowing so much as it’s shifting. Two decades ago, an article like Cotton’s could easily be published, an essay arguing for abolishing prisons or police would languish in the submissions pile, and a slogan like “Black Lives Matter” would be controversial. Today, Black Lives Matter is in the sphere of consensus, abolishing prisons is in legitimate controversy, and there’s a fight to move Cotton’s proposal to deploy troops against US citizens into deviance. The idea space is just as large as it’s been in the past — perhaps larger — but it is in flux, and the fight to define its boundaries is more visible.

“Those are political decisions,” says Charles Whitaker, dean of the Medill School of Journalism. “They are absolutely governed by politics — either our desire to highlight certain political views or not highlight them, or to create this impression that we’re just a marketplace of ideas.”

The media is changing because the world is changing

- First, business models built around secure local advertising monopolies collapsed into the all-against-all war for national, even global, attention that defines digital media.

- Second, the nationalization of news has changed the nature of the audience. The local business model was predicated on dominating coverage of a certain place; the national business model is about securing the loyalties of a certain kind of person.

- Third, America is in a moment of rapid demographic and generational change. Millennials are now the largest generation, and they are far more diverse and liberal than the generations that preceded them.

- Fourth, the rise of social media empowered not just the audience but, crucially, individual journalists, who now have the capacity to question their employer publicly, and alchemize staff and public discontent into a public crisis that publishers can’t ignore.

The media prefers to change in private. Now it’s changing in public.

The news media likes to pretend that it simply holds up a mirror to America as it is. We don’t want to be seen as actors crafting the political debate, agents who make decisions that shape the boundaries of the national discourse. We are, of course. We always have been.

“When you think in terms of these three spheres — sphere of consensus, of legitimate debate, and of deviancy — a new way of describing the role for journalism emerges, which is: They police what goes in which sphere,” says Jay Rosen, who teaches journalism at NYU. “That’s an ideological action they never took responsibility for, never really admitted they did, never had a language for talking about.”

“Organizations that have embraced the mantra that they need to diversify have not as quickly realized that diversifying means they have to be a fundamentally different place,” says Jelani Cobb, the Ira A. Lipman professor at the Columbia Journalism School and a staff writer at the New Yorker. “If you want to bring in different perspectives, you’ll have a different culture and different environment that will lead you to make different decisions.”

[Full Piece]

York…say his name.

@SHEDELL6

‘This is York. He was part of the Lewis and Clark expedition. York was a slave and even after his faithful service to the expedition they refused to liberate him. The whole PNW worships Lewis and Clark but little mention of York.’

‘Rain without thunder and lightening…’

The Atlantic

Why Minneapolis Was the Breaking Point

Black men and women are still dying across the country. The power that is American policing has conceded nothing.

Seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier was on her way out the door to a Memorial Day bonfire on the other side of town when her 9-year-old cousin made a request: Would Frazier walk her to a nearby store? Of course, Frazier replied.

She and her cousin were on their way back home, at the corner of 38th and Chicago, just south of downtown, when Frazier spotted a distraught man sprawled on the pavement. A pile of police officers was holding him down. At least one of the cops seemed to be on top of the man’s neck.

Frazier pulled out her cellphone and hit Record.

Within hours, the whole world had seen the video: Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin driving his knee into the neck of 46-year-old George Floyd, not only until Floyd died but for minutes after his life had been extinguished. What came next was a national crisis.

When I first sat down to begin writing this story, parts of many American cities were on fire and police officers in dozens of places were committing indiscriminate acts of violence—unleashing tear gas, rubber bullets, and worse—against the citizenry they had sworn an oath to serve and protect. Elected officials were pleading for peace as parts of their cities burned and the nation, watching in real time on television, asked “Why?”

Decades earlier, there’d been the determined journalism of Ida B. Wells, whose Memphis newspaper was burned to the ground by white supremacists. Wells is best remembered for her crusading work in the 1890s, which not only documented the frequency of southern lynchings but also provided what we’d now consider data analysis in order to disprove the racist lie that lynchings were happening because black men had a particular lust for and inclination to rape white women. Less well known is that Wells also dispatched herself to the scene of cases of police violence, providing essential scrutiny of an equally American strand of homicidal impunity.

“Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want the WESLEY LOWERY is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and the author of They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement. He is currently a correspondent for 60 in 6, a spin-off of 60 Minutes on the mobile app Quibi.” the former slave Frederick Douglass proclaimed in 1857. “They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.”

“This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle,” Douglass continued, before arriving at a more widely quoted sentence: “Power concedes nothing without a demand.”

Racism is not to blame, the thinking popular among at least some conservatives goes. It’s the people fighting racism who are the problem. If everyone could just stop talking about all of this stuff, we could go “back” to being a peaceful, united country. No one seems to be able to answer when, precisely, in our history that previous moment of peace, justice, and racial harmony occurred.

WESLEY LOWERY is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and the author of They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement. He is currently a correspondent for 60 in 6, a spin-off of 60 Minutes on the mobile app Quibi.

[Full Article]