COVID COMPASSION

As individuals and communities, we can respond with justice and compassion, or we can double down on the pursuit of accumulation and power, with no more than a return to business as usual.

-Father Richard Rohr

Center for Action & Contemplation

‘The pandemic has severely attacked vulnerable communities of color, including tribal communities whose members may not have access to adequate health care nor clean water, we turn to a young voice from the Navajo Nation.’

[Desperado Philosophy]

Aware that the pandemic has severely attacked vulnerable communities of color, including tribal communities whose members may not have access to adequate health care nor clean water, we turn to a young voice from the Navajo Nation (Diné), Alastair Lee Bitsóí, relayed from the pages of the Navajo Times. Excerpts below, with images from the studio of Tony Abeyta.

https://desperadophilosophy.net/2020/05/09/nature-in-control/amp/?__twitter_impression=true

[Investigative, compassionate journalism. -dayle]

‘Life expectancy gap between black & white Chicagoans, largest in the country: Structural racism, concentrated poverty, economic exploitation & chronic stress cause what’s known as biological weathering.’

ProPublica

ProPublica is an independent, non-profit newsroom that produces investigative journalism in the public interest. THE FIRST 100 COVID-19 Took Black Lives First. It Didn't Have To.

“We’re not going to reverse this in a moment, overnight, but we have to say it for what it is and move forward decisively as a city, and that’s what we will do,” she said. “This is about health care accessibility, life expectancy, joblessness and hunger.”

ProPublica’s reporting also revealed other patterns, factors that could — and should — have been addressed and which almost certainly exist in other communities experiencing similar disparities. Even though many of these victims had medical conditions that made them particularly susceptible to the virus, they didn’t always get clear or appropriate guidance about seeking treatment. They lived near hospitals that they didn’t trust and that weren’t adequately prepared to treat COVID-19 cases. And perhaps most poignantly, the social connections that gave their lives richness and meaning — and that played a vital role in helping them to navigate this segregated city that can at times feel hostile to black residents — made them more likely to be exposed to the virus before its deadly power became apparent.

The city [Chicago] announced the Racial Equity Rapid Response Team in partnership with West Side United, with a goal to “bring a hyper local public health strategy to targeted communities.” In the weeks since, the team has held tele-town halls, delivered thousands of door hangers and postcards with targeted information, and distributed 60,000 masks for residents in the predominantly black communities of Austin, Auburn Gresham and South Shore.

https://features.propublica.org/chicago-first-deaths/covid-coronavirus-took-black-lives-first/

So much new & good is going to come from this. We can stop deluding ourselves that our current way of organizing our society is either sane or even survivable! That had to come first in order to rock us to our core, to humble us. Now we’ll be open to new ideas in a whole new way.

-Marianne Williamson

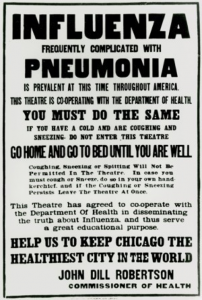

A poster from 1918 asks Chicagoans to self-quarantine if they have symptoms of the flu. For more, see “Don’t Spit! Pandemic Posters Through the Years.” (Courtesy National Library of Medicine)

The Atlantic

Disaster Studies

Pandemics Leave Us Forever Altered

by Charles C. Mann

What history can tell us about the long-term effects of the coronavirus

Just a few decades after the pandemic, American-history textbooks by the distinguished likes of Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Richard Hofstadter, Henry Steele Commager, and Samuel Eliot Morison said not a word about it. The first history of the 1918 flu wasn’t published until 1976—I drew some of the above from it. Written by the late Alfred W. Crosby, the book is called America’s Forgotten Pandemic.

Americans may have forgotten the 1918 pandemic, but it did not forget them. Garthwaite matched NHIS respondents’ health conditions to the dates when their mothers were probably exposed to the flu. Mothers who got sick in the first months of pregnancy, he discovered, had babies who, 60 or 70 years later, were unusually likely to have diabetes; mothers afflicted at the end of pregnancy tended to bear children prone to kidney disease. The middle months were associated with heart disease.

Other studies showed different consequences. Children born during the pandemic grew into shorter, poorer, less educated adults with higher rates of physical disability than one would expect. Chances are that none of Garthwaite’s flu babies ever knew about the shadow the pandemic cast over their lives. But they were living testaments to a brutal truth: Pandemics—even forgotten ones—have long-term, powerful aftereffects.

[…]

The convulsive social changes of the 1920s—the frenzy of financial speculation, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, the explosion of Dionysian popular culture (jazz, flappers, speakeasies)—were easily attributed to the war, an initiative directed and conducted by humans, rather than to the blind actions of microorganisms. But the microorganisms likely killed more people than the war did. And their effects weren’t confined to European battlefields, but spread across the globe, emptying city streets and filling cemeteries on six continents.

Unlike the war, the flu was incomprehensible—the influenza virus wasn’t even identified until 1931. It inspired fear of immigrants and foreigners, and anger toward the politicians who played down the virus. Like the war, influenza (and tuberculosis, which subsequently hit many flu sufferers) killed more men than women, skewing sex ratios for years afterward. Can one be sure that the ensuing, abrupt changes in gender roles had nothing to do with the virus?

[…]

To save themselves from the disease, scared Europeans sought favor from the heavens, most famously taking off their clothes in groups and striking one another with whips and sticks. Images of half-nude flagellants have, since Monty Python, become a comic staple. Far less comical was the accompanying flood of anti-Semitic violence. As it spread through Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, and the Low Countries, it left behind a trail of beaten cadavers and burned homes.

Absent the diseases, it is difficult to imagine how small groups of poorly equipped Europeans at the end of very long supply chains could have survived and even thrived in the alien ecosystems of the Americas. “I fully support banning travel from Europe to prevent the spread of infectious disease,” the Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle remarked after President Trump announced his plan to do this. “I just think it’s 528 years too late.”

For Native Americans, the epidemic era lasted for centuries, as did its repercussions. Isolated Hawaii had almost no bacterial or viral disease until 1778, when the islands were “discovered” by Captain James Cook. Islanders learned the cruel facts of contagion so rapidly that by 1806, local leaders were refusing to allow European ships to dock if they had sick people on board. Nonetheless, Hawaii’s king and queen traveled from their clean islands to London, that cesspool of disease, arriving in May 1824. By July they were dead—measles.

Later it occurred to me that a possible legacy of Hong Kong’s success with SARS is that its citizens seem to put more faith in collective action than they used to. I’ve met plenty of people there who believe that the members of their community can work together for the greater good—as they did in suppressing SARS and will, with luck, keep doing with COVID-19. It’s probably naive of me to hope that successfully containing the coronavirus would impart some of the same faith in the United States, but I do anyway.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/06/pandemics-plagues-history/610558/

Leave a Reply