Cultural Corona

March 17, 2020“Without trust and global solidarity we will not be able to stop the coronavirus epidemic we will not be able to stop the coronavirus epidemic, and we are likely to see more such epidemics in the future. But every crisis is also an opportunity.

-Yuval Noah Harari

Noah Harari is a historian, philosopher and the bestselling author of Sapiens, Homo Deusand 21 Lessons for the 21st Century.

Perhaps the most important thing people should realize about such epidemics, is that the spread of the epidemic in any country endangers the entire human species. This is because viruses evolve. Viruses like the corona originate in animals, such as bats. When they jump to humans, initially the viruses are ill-adapted to their human hosts. While replicating within humans, the viruses occasionally undergo mutations. Most mutations are harmless. But every now and then a mutation makes the virus more infectious or more resistant to the human immune system – and this mutant strain of the virus will then rapidly spread in the human population. Since a single person might host trillions of virus particles that undergo constant replication, every infected person gives the virus trillions of new opportunities to become more adapted to humans. Each human carrier is like a gambling machine that gives the virus trillions of lottery tickets – and the virus needs to draw just one winning ticket in order to thrive.

(Original Caption) Photo shows a scene in the influenza Camp at Lawrence, Maine, where patients are given fresh air treatment. this extreme measure was hit upon as the best way of curbing the epidemic. Patients are required to live in these camps until cured.

As you read these lines, perhaps a similar mutation is taking place in a single gene in the coronavirus that infected some person in Tehran, Milan or Wuhan. If this is indeed happening, this is a direct threat not just to Iranians, Italians or Chinese, but to your life, too. People all over the world share a life-and-death interest not to give the coronavirus such an opportunity. And that means that we need to protect every person in every country.

[…]

Today humanity faces an acute crisis not only due to the coronavirus, but also due to the lack of trust between humans. To defeat an epidemic, people need to trust scientific experts, citizens need to trust public authorities, and countries need to trust each other. Over the last few years, irresponsible politicians have deliberately undermined trust in science, in public authorities and in international cooperation. As a result, we are now facing this crisis bereft of global leaders that can inspire, organize and finance a coordinated global response.

[…]

What does this history teach us for the current Coronavirus epidemic?

First, it implies that you cannot protect yourself by permanently closing your borders. Remember that epidemics spread rapidly even in the Middle Ages, long before the age of globalization. So even if you reduce your global connections to the level of England in 1348 – that still would not be enough. To really protect yourself through isolation, going medieval won’t do. You would have to go full Stone Age. Can you do that?

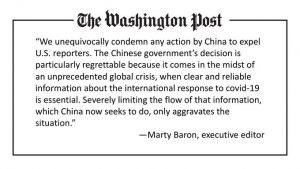

Secondly, history indicates that real protection comes from the sharing of reliable scientific information, and from global solidarity. When one country is struck by an epidemic, it should be willing to honestly share information about the outbreak without fear of economic catastrophe – while other countries should be able to trust that information, and should be willing to extend a helping hand rather than ostracize the victim. Today, China can teach countries all over the world many important lessons about coronavirus, but this demands a high level of international trust and cooperation.

[…]

In this moment of crisis, the crucial struggle takes place within humanity itself. If this epidemic results in greater disunity and mistrust among humans, it will be the virus’s greatest victory. When humans squabble – viruses double. In contrast, if the epidemic results in closer global cooperation, it will be a victory not only against the coronavirus, but against all future pathogens.

https://time.com/5803225/yuval-noah-harari-coronavirus-humanity-leadership/

VOX

Scientists warn we may need to live with social distancing for a year or more

Researchers say we face a horrible choice: practice social distancing for months or a year, or let hundreds of thousands die.

Life in America — and in many countries around the world — is changing drastically. We’re physically distanced from our favorite people, we’re avoiding our favorite public places, and many are financially strained or out of work. The response to the Covid-19 pandemic is infiltrating every aspect of life, and we’re already longing for it to end. But this fight may not end for months or a year or even more.

We’re in this because public health experts believe social distancing is the best way to prevent a truly horrific crisis: perhaps hundreds of thousands or more if our health care system is overwhelmed with severe Covid-19 cases, people who require ventilators and ICU beds that are now growing limited in supply.

“Some may look at [the guidelines] … and say, well, maybe we’ve gone a little bit too far,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a member of the White House coronavirus task force, at a Monday White House press conference. “They were well thought out. And the thing that I want to reemphasize … when you’re dealing with an emerging infectious diseases outbreak, you are always behind where you think you are if you think that today reflects where you really are.”

How long, then, until we’re no longer behind and are winning the fight against the novel coronavirus? The hard truth is that it may keep infecting people and causing outbreaks until there’s a vaccine or treatment to stop it.

“I think this idea … that if you close schools and shut restaurants for a couple of weeks, you solve the problem and get back to normal life — that’s not what’s going to happen,” says Adam Kucharski, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and author of The Rules of Contagion, a book on how outbreaks spread. “The main message that isn’t getting across to a lot of people is just how long we might be in this for.”

Ugh, whyyyyy???

The reason we may be in for an extended period of disruption, Kucharski says, is that the main thing that seems to be working right now to fight this pandemic is severe social distancing policies.

Drop those measures — allow people to congregate in big groups again — while the virus is still out there, and it can start new outbreaks that gravely threaten public health, particularly the older and chronically ill people, those most vulnerable to severe illness. “There’s no way [the virus] is going to go away in the next few weeks,” he says.

The way things are looking now, we’ll need something to stop the virus to truly end the threat. That’s either a vaccine (there are some now entering clinical trials but it could be a year before they are approved) or herd immunity. This is when enough people have contracted the virus, and have become immune to it, to slow its spread.

Herd immunity is not guaranteed. Currently it’s unclear if, after a period of months or years, a person can lose their immunity and become reinfected with the virus (which would make achieving herd immunity more difficult). Also, herd immunity will come at the cost of millions of people becoming infected, and possibly millions of people dying.

A new scientific report stresses: Only the most severe distancing measures can prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths

A sobering new report from the COVID-19 Response Team at the Imperial College of London underscores the need to keep social distancing measures in place for a long period.

It outlines two scenarios for combating the spread of the outbreak. One is mitigation, which focuses on “slowing but not necessarily stopping epidemic spread.” Another is suppression, “which aims to reverse epidemic growth.”

In their analysis, isolation of confirmed cases and quarantine of older adults without social distancing would still result in hundreds of thousands of deaths, and an “eight-fold higher peak demand on critical care beds over and above the available surge capacity in both [Great Britain] and the US.”

(Remember, all projections of possible deaths come with uncertainty and are greatly dependent on how we respond. Estimates can change based on variables that are not quite yet understood: like the role kids play in transmitting the virus, and the potential for the virus to show seasonal effects.)

Bars and restaurants will become takeout-only, and businesses from movie theaters and casinos to gyms and beyond will be shuttered throughout New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, agrees that the social distancing measures might need to be in place for at least months. “I don’t think people are prepared for that and I am not certain we can bear it,” she writes in an email. “I have no idea what political leaders will decide to do. To me, even if this is needed, it seems unsustainable.” She adds that she might just be feeling pessimistic, but “it’s really hard for me to imagine this country staying home for months.”

“Once things get better, we will have to take a step-wise approach toward letting up on these measures and see how things go to prevent things from getting worse again,” says Krutika Kuppalli, an infectious disease physician and Emerging Leader in Biosecurity fellow at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security.

We also don’t know how long we’re in for because we don’t know how bad the outbreak is in the US — due to the lack of testing.

It’s okay to be upset by all of this. And there are still a lot of unknowns about this virus, and how it will all play out. Perhaps the worst will spare us. But we still need to prepare for it and tap into our resiliency. Life may feel very hard and very stressful over the next several months. It’s a real burden, and you don’t have to like it. But know: This pandemic will end eventually. What we don’t yet know is when.

“Although we may have to be physically apart… we can come together in ways we never have before”

WHO chief Dr Tedros says to overcome the coronavirus pandemic the “spirit of human solidarity must become even more infectious than the virus”

‘How Can I Make You Care?’ BuzzFeed Reporter & Idaho Native On Culture & Coronavirus

Molly Wampler

Anne Helen Petersen is a senior culture writer at BuzzFeed News, She’s based in Montana. Petersen has been covering the culture of the coronavirus, specifically how Americans got to this point in the crisis and why so many of us are having a hard time convincing loved ones to care about this pandemic.

Her recent articles (How Millennials Are Talking To Their Boomer Relatives About The Coronavirus, i don’t know how to make you care about other people) have struck a chord with folks across the country.

She joins Idaho Matters from Montana to talk about what she’s learned reporting on this pandemic in the U.S.

BUZZFEED

How Millennials Are Talking To Their Boomer Relatives About The Coronavirus

The big issue? So many of them don’t want to consider themselves “old” or “vulnerable.”

“There’s a general attitude that we are making a big deal out of nothing. A lot of ‘we deal with the flu every year.’”

There are multiple reasons for this split in approach, from general disposition (preparedness-minded to I’ll-deal-with-it-when-I-have-to) to one’s primary source of news and information. Add in inconsistent messaging from the government and differing “recommendations” from state to state, and it’s easy to understand why people have developed such disparate attitudes about how to proceed in their daily lives. There’s so much that’s unknown about how exactly the spread of the coronavirus will impact the United States, save to observe what’s happened in places that immediately launched extensive testing and quarantine efforts (like Hong Kong and South Korea, both of which have significantly mitigated the disease’s spread) and those that took longer (Italy and Iran).

But here’s what is clear: Even though many people who contract the coronavirus will only experience flulike symptoms, 15% to 20% will develop serious, life-threatening symptoms that demand hospitalization. The statistics from the outbreak in China are incredibly useful in figuring out who’s most at risk: “older adults” (anyone over 60); anyone with heart disease, diabetes, or lung disease; and anyone who is “immunocompromised” (a group that includes about 10 million people in the US, including those with cancer, HIV, and organ transplant recipients).

At this point, the resistance seems to be divided into three overarching areas: misinformation, disidentification, and general stubbornness. Like other types of contemporary misinformation, inaccurate and fake stories about COVID-19 has been spreading most aggressively on Facebook — where, as my colleague Craig Silverman has pointed out, older people are often purposefully targeted by sites and pages trafficking in hyperpartisan rhetoric and straight-up falsehoods.

“My parents and grandparents are on an IV drip of Fox News directly to their brains and believe COVID-19 is a hoax being used as a weapon against the president.”

One person who’s been trying to get his grandfather to take the threat of COVID-19 seriously sent me a screenshot of his latest text, which featured a picture that he’d taken of an image on his own computer. The photo is of a whiteboard, with the dates of previous epidemics, and the caption “POSTED AT A DOCTORS OFFICE TODAY.” (The information in the image has been widely circulating across Facebook and Twitter, but has been officially debunked.) “I don’t think you have to be afraid of the coronavirus,” the grandfather said. “As this post says, diseases appear every year to disrupt the voting process. It is good to be cautious but I believe it’s just another of Satan’s tactics to prevent people from following Jesus.”

[…]

You can also attempt to show, not tell: Show what’s happening in Italy and how the hospitals are overwhelmed, despite full quarantine measures. Explain that if the same thing happens here, they’ll need to be prepared: with meds, with food, with supplies. (Then offer to help them get their hands on those items, as many might be reticent to navigate new systems, like online grocery ordering; one person told me it took an hour to complete her 96-year-old great-grandmother’s order, because she was specifying items like “five green bananas,” but it was worth it: She wasn’t going to the grocery store.)

[…]

Upsetting routine, and replacing it with social isolation for an unspecified amount of time — something that many older people work so hard to counteract — is incredibly difficult to stomach. You can make that easier by promising a whole lot of FaceTiming or video-chatting, and offering to show their friends how to do the same. One woman who works for a public health organization told me that she gradually seeded information to her grandparents and parents, getting them used to the idea of future self-quarantine, before they actually decided to take action.

Empty seats at Goodyear Ballpark in Goodyear, Arizona, March 12. The MLB suspended spring training due to the ongoing threat of the coronavirus outbreak. [Getty]

“My dad was harder,” she explained. “I had to emphasize just how much of a risk he was being to my mom by going out. And eventually I just told him that I know he doesn’t like to overreact, and just generally thinks he’s immune to things, but that I had never really asked him for a favor, and that I was now. I needed him to listen to me, even if he didn’t want to.”

“My mom told me, ‘We are not going to stop living,’ and I said, “That is the point!’”

In some cases, the only thing that will make people take action is others forcing them to. The woman whose immunocompromised mom wouldn’t stop volunteering at the hospital contacted me again today. “The hospital sent all the older volunteers home,” she said. “My mom was a little sad about it, but we had a good conversation about safety and being around for her grandkids.”

Our parents and grandparents have spent their lives being the ones giving us advice and telling us what to do. Reversing that dynamic can feel incredibly unnatural. But even if your parents or grandparents aren’t listening now, they’re going to need you later. Keep trying, keep talking — and, if all else fails, appeal to their parental instincts. “Telling my parents I’m scared has been helpful,” a woman named Mary told me. “They’re way more incentivized to protect me from the fear.” ●

[Important read-full link]

Journalism in the Time of Corona

Seattle Times

From the editor: As we face the coronavirus challenge together, thank you for your support

While the region mobilizes to respond to the spread of COVID-19, I want to take a moment to thank you for your support. So many of you have reached out to me and our news staff with your tips, questions and gratitude for our coronavirus coverage. We have been working hard to bring you the most current, factual information on this quickly evolving crisis.

It’s been two astonishing weeks — for all of you, and for all of us.

In my 35 years as a journalist, I can say I’ve never felt so keenly the importance of local journalism to our community. And in my 27 years at The Seattle Times, I’ve never seen the entire company rally behind our mission the way we are now.

We are working at a breakneck pace to report rapidly changing news developments such as closures, new cases and travel restrictions. We are asking tough questions to hold officials accountable, while also telling of the extreme challenges they face. We’re capturing moments of heart-wrenching struggle and uplifting acts of kindness.

And we are intently focused on providing you with the resources you need to navigate this unsettling time: things like tips for keeping your home virus-free, and this detailed graphic explaining how the virus takes hold and the steps you can take to stay safe.

Many of you have asked what we’re doing to safeguard the health of our staff and the public.

While we don’t pretend to have all the answers — no one does — we’re doing our best. For the first time ever, every newsroom employee is working remotely from home, as are all company employees who are able to do so.

For those who must go out to do their jobs, we are taking extra precautions.

We’ve told all Times employees, including our reporters, photographers and video journalists, to avoid areas where someone has tested positive for COVID-19, and we’ve shared public health guidelines such as keeping a distance of 6 feet or more from people whenever possible. We opted not to provide masks, after health officials advised against their use for healthy people. But we have provided hand sanitizer and have bought special protective gear for those who need it to report from inside hospitals or other high-risk places.

For our operations and circulation staff, as well as our carriers — who don’t have the option of working from home — we are taking every step we can to safeguard their health.

Our staff is fueled by your support. The kind notes, calls and social media messages we are receiving each day have kept us going at moments when we’ve felt exhausted, worried or discouraged.

We’re also heartened to see how many people are coming to us to stay informed. Readership of our website has been triple our normal volume — even 10 times the volume at key breaking-news moments. And despite the fact that we’ve made our coronavirus stories free as a public service, this coverage has drawn new subscribers at record levels.

That’s critical, especially given the fact that while the world feels changed, the economic challenges facing the news business remain the same. If you don’t already subscribe but want us to continue fulfilling the critical role of informing you, please consider joining us in this mission by subscribing. You can do so at seattletimes.com/subscribe or by calling 206-464-2121 or 800-542-0820.

As we head into uncertain times, here are some free useful resources to keep handy:

- Our daily live updates. You can find these on seattletimes.com each morning with need-to-know breaking news and information updated throughout the day.

- A visual guide outlining facts about COVID-19 and precautions on how to stay healthy.

- And a page where you can find all of our reporting on this topic, with the latest coverage at the top.

Additionally, if you have news tips, story ideas or feedback on any of our coverage, please email us at newstips@seattletimes.com.

For all of us, living in this new reality means adapting very suddenly to new routines. We’ve certainly felt that ourselves, and unlike with many big news stories we cover, we are experiencing this one right along with the people we’re writing about.

In fact, that’s one positive side effect of this pandemic: We’re becoming more empathetic by the day, and we see you doing the same.

I’d love to hear from you if you have thoughts or questions for me personally. Feel free to write me at michmflo@seattletimes.com.

On behalf of all of us at The Times, I share our deep appreciation for your continued support of us, and of local journalism.

Zooming at home.

A short manifesto from author and former dot com exec/blogger Seth Godin.

The conversation

“A short manifesto about the future of online interaction

The world is changing. Faster and more suddenly than most of us expected.

And beyond the fraught health emergencies that so many are going through, many of us are being asked to quickly move our meetings and our classes online.

Fortunately, there are powerful and inexpensive tools to do just that. Unfortunately, we’re at risk at adopting a new status quo that’s even worse than the one it replaces.

We can make it better.

You have a chance to reinvent the default, to make it better. Or we can maintain the status quo. Which way will you contribute?

Rather than doing what we’ve always done in real-life (but online, and not as well), what if we did something better instead?

Here’s what we think we get from a real-life meeting:

- A chance for people to come together and discuss important issues.

Here’s what we actually get:

- A chance for some people to demonstrate their status and power.

- A chance for most people to take notes and seek to avoid responsibility.

Real-life meetings are among the most hated part of work for the typical office worker. They last too long, happen too often and bore and annoy most of the people who attend. They can mostly be replaced by a memo (if they’re about transferring information) or they could be better run (if they’re about transforming information.)

But at least you’re not in school.

The traditional school day is nothing but a meeting. Eight hours of it. In which you are almost never asked to contribute, or, if you are, it’s at great risk, both social and in terms of academic standing.

And now, because of worldwide events, local meetings and local schooling are going online.

It will lead to one of two things:

1. Just like the ones in real-life, except worse.

2. Something new and something better.

Forgive me for not being optimistic, but if what we’re seeing is any guide, we’re defaulting to the first (wrong) choice.

It’s worse because you can check your phone, your email and your fridge. It’s worse because you can more clearly see the faces of people who are bored right in front of you who can’t realize you can see them.

[Did you know that there’s a ‘focus’ button in Zoom and other tools that shows the organizer when people in the room have put Chrome or something else in front and are only sort-of paying attention? It’s there to ensure compliance and it’s there because we’re figuring out how to not pay attention.]

The compliance of the mandatory Zoom meeting is not nearly as firm as it is in real life. It’s like an episode of the Office, except it’s happening millions of times a day.

And then when we try to move classes online! First we coerced students to pay attention with grades, withholding what they want and need (a certificate, a diploma, an A) in exchange for them giving up their agency and freedom and youth.

Then, because we weren’t getting enough compliance, we invented the clicker.

It’s a pernicious digital device that probably had good intent behind it, but like so many things that are industrialized, it’s now more of a weapon than a tool.

How the clicker works: Every student at a large university is required to buy one. Yes, you need to spend more of your own money to be controlled. It has built-in ID (it knows who you are) and wifi and GPS. Inside the lecture hall, you need to click. Click to prove you’re there. Click to prove you’re awake. Click to prove you can repeat what the professor just said.

Sure, it’s possible to use clickers to produce powerful and engaging discussion. My quick research seems to indicate that this almost never happens. It’s easier to have the student simply pay for compliance in exchange for the certificate.

So, we have a few problems:

1. The in-person regime of meetings and school is riddled with problems around status, wasted time, compliance, boredom and inefficient information flow.

2. Moving to online gives up the satisfaction of the status quo, diminishes the ego satisfaction for those seeking status, and creates even more challenges with compliance, boredom and the rest.

But…

There’s a solution. A straightforward and non-obvious choice.

Let’s have a conversation instead.

A conversation involves listening and talking. A conversation involves a perception of openness and access and humanity on both sides.

People hate meetings but they don’t hate conversations.

People might dislike education, but everyone likes learning.

If you’re trapped in a room of fifty people and the organizer says, “let’s go around the room and have everyone introduce themselves,” you know you’re in for an hour of unhappiness. That’s because no one is listening and everyone is nervously waiting for their turn to talk.

But if you’re in a conversation, you have to listen to the other person. Because if you don’t, you won’t know what to say when it’s your turn to talk.

Conversations reset the power and compliance dynamic, because conversations enable us to be heard.

Conversations generate their own interest, because after you speak your piece, you’re probably very focused on what someone is going to say in response.

You don’t have to have a conversation, but if you choose to have one, go all in and actually have one.

And here’s the punchline:

The digital world enables a new kind of conversation, one that scales, one that cannot possibly be replicated in the real world.

There’s even a special button for it in Zoom, and if you have enrollment and the passion to engage with it, you can use it to create magic.

We know, because we’ve done it at Akimbo. We’ve created important and useful conversations for a group of 700 people at a time. More than 97% of the people who joined our online meeting were in it at the end. With no coercion, no diploma, no grades and no clickers.

If we want to, we can use Zoom to create conversations, not a rehash of tired power dynamics. We can create peer to peer environments where conversations happen.

Here’s how it works:

0. The most important: Only have a real-time meeting if it deserves to be a meeting. If you need people to read a memo, send a memo. If you need students to do a set of problems, send the problems. If you want people to watch a speech or talk, then record it and email it to them. Meetings and real-time engagements that are worthy of conversations are rare and magical. Use them wisely.

1. People come to the meeting ready to have a conversation. If they’re coerced to be there, everything else gets more difficult.

2. Part of being engaged means being prepared. Consider this simple 9 point checklist.

3. Organize a conversation. That can’t work at any scale more than five. How then, to do an event with hundreds of people? The breakout.

A standard zoom room permits you to have 250 people in it. You, the organizer, can speak for two minutes or ten minutes to establish the agenda and the mutual understanding, and then press a button. That button in Zoom will automatically send people to up to 50 different breakout rooms.

If there are 120 people in the room and you set the breakout number to be 40, the group will instantly be distributed into 40 groups of 3.

They can have a conversation with one another about the topic at hand. Not wasted small talk, but detailed, guided, focused interaction based on the prompt you just gave them.

8 minutes later, the organizer can press a button and summon everyone back together.

Get feedback via chat (again, something that’s impossible in a real-life meeting). Talk for six more minutes. Press another button and send them out for another conversation.

This is thrilling. It puts people on the spot, but in a way that they’re comfortable with.

If you’re a teacher and you want to actually have conversations in sync, then this is the most effective way to do that. Teach a concept. Have a breakout conversation. Have the breakouts bring back insights or thoughtful questions. Repeat.

A colleague tried this technique at his community center meeting on Sunday and it was a transformative moment for the 40 people who participated.

If you want to do a lecture, do a lecture, but that’s prize-based education, not real learning. If people simply wanted to learn what you were teaching, they wouldn’t have had to wait for your lecture (or pay for it). They could have looked it up online.

But if you want to create transformative online learning, then allow people to learn together with each other.

Connect them.

Create conversations.”