‘…because the government lied, more people died.’

February 28, 2020‘An expert on the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic wrote a piece 2 yrs ago on lessons of why that outbreak was so deadly.

His conclusion: govt officials, desperate to keep morale up during WWI, didn’t tell the truth.

And because the government lied, more people died.’

-Ian Bassin, former associate White House Council

How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America

The toll of history’s worst epidemic surpasses all the military deaths in World War I and World War II combined. And it may have begun in the United States

Although some researchers argue that the 1918 pandemic began elsewhere, in France in 1916 or China and Vietnam in 1917, many other studies indicate a U.S. origin. The Australian immunologist and Nobel laureate Macfarlane Burnet, who spent most of his career studying influenza, concluded the evidence was “strongly suggestive” that the disease started in the United States and spread to France with “the arrival of American troops.” Camp Funston had long been considered as the site where the pandemic started until my historical research, published in 2004, pointed to an earlier outbreak in Haskell County.

Wherever it began, the pandemic lasted just 15 months but was the deadliest disease outbreak in human history, killing between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide, according to the most widely cited analysis. An exact global number is unlikely ever to be determined, given the lack of suitable records in much of the world at that time. But it’s clear the pandemic killed more people in a year than AIDS has killed in 40 years, more than the bubonic plague killed in a century.

The impact of the pandemic on the United States is sobering to contemplate: Some 670,000 Americans died.

A ravaged lung (at the National Museum of Health and Medicine) from a U.S. soldier killed by flu in 1918.(Cade Martin)

We are arguably as vulnerable—or more vulnerable—to another pandemic as we were in 1918. Today top public health experts routinely rank influenza as potentially the most dangerous “emerging” health threat we face. Earlier this year, upon leaving his post as head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tom Frieden was asked what scared him the most, what kept him up at night. “The biggest concern is always for an influenza pandemic…[It] really is the worst-case scenario.” So the tragic events of 100 years ago have a surprising urgency—especially since the most crucial lessons to be learned from the disaster have yet to be absorbed.

Against this background, while influenza bled into American life, public health officials, determined to keep morale up, began to lie.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/

‘This is how human power can look.’

February 27, 2020“That idea that power cannot be accompanied by notions of compassion and kindness and empathy. That’s something that I refuse to accept.”

‘Picture a leader of a country and, chances are, you’ll picture a man.

This isn’t surprising. The majority of world leaders are men, so our ideas about the characteristics of leadership are so deeply ingrained, it’d take someone pretty outstanding to change them.

Far-right, ‘strongman’ rulers are on the rise around the world. But not in New Zealand, where Jacinda Ardern, the 39-year-old progressive prime minister, is challenging perceptions of what a leader should look like and showing us that society is ready for change.

This prime minister is showing the world that leadership isn’t a male trait. It’s a human one

Imagine a powerful person. The prime minister of a rich country, say, taking the stage for a press conference. Think of the voice, the dress sense, the way a prime minister speaks and sounds. Who do you see in front of you? Let me guess.

A man in a suit.

This is our reflex, our stock idea of a prime minister. It’s an image that plays tricks on many female politicians. Take Senator Elizabeth Warren, a prominent candidate in the Democratic primaries to select a challenger to Donald Trump, the US president, in elections in November this year. After a promising start in autumn 2019, Warren’s campaign has been plagued by loud speculation about her “electability”. She’s a woman, after all.

According to Warren, her rival Senator Bernie Sanders told her during a private conversation in 2018 that a woman can’t win in 2020. It’s a claim that Sanders has denied, but the grounds for such opinions are easy to find. In the 2016 presidential race, Hillary Clinton fought Trump in a tough, often sexist campaign. For all her political experience, the word went around that a woman was not “presidential” and hence not “electable”. The same assumptions have hurt Warren’s campaign.

Governments in Hungary, United States and Brazil are led by macho misogynists. In New Zealand, the opposite happened.

Is it credible in 2020 that women are still not electable to the highest level of power? If you follow the news, you’ll understand the roots of this question. Trump won in 2016 despite – or perhaps, thanks to? – numerous accusations of sexual misconduct and an audio recording of his infamous “Grab ’em by the pussy” comment during a tour of a television studio in 2005.

In New Zealand, the exact opposite happened.

Since 2017, the New Zealand government has been led by a woman who is still (until July) under 40 years old. Ardern’s victory can be compared to other recent political insurgents Barack Obama, Justin Trudeau and Emmanuel Macron.

It is a measure of international interest that “Jacindamania” has entered the political lexicon. At the same time, however, the same political climate has rained hatred upon Ardern. Her personal style has upset millennia-old ideas about men, women and power: ideas made visible by the sexist reactions which follow her.

The phenomenon of New Zealand’s second female prime minister shows how the prevalence of these ingrained cultural ideas and, thanks to Ardern and others, how such thinking can shift.

Her message is that people depend on one another – not on money, numbers or achievements.

[…]

Mary Beard, a British classicist, cites this incident in her 2017 book Women & Power, a history of misogyny from Athens and Rome to today. She begins with an account of Homer’s Odyssey, in which Queen Penelope, wife of Ulysses, is silenced in public by her newly grown-up son because “speech is a man’s business”. To Roman orators, high (female) voices expressed “cowardice”. For too many famous novelists, female voices resembled the mooing of cows or the braying of donkeys, sounds which polluted language.

Sharp, too high, unpleasant – the voices of female politicians or leaders would have ‘no authority’

Beard’s book describes a serial smear campaign against the female voice. She shows how prevailing ideas about eloquence and rhetoric are rooted in a classical tradition which dismissed female voices as an aberration. To this day, women are much more often said to be squeaking, whining, squawking, screaming or cackling. Or that their voices are “just uncomfortable” to hear. Like Warren’s, described by a journalist as “unbearably shrill”.

Preserve our light.

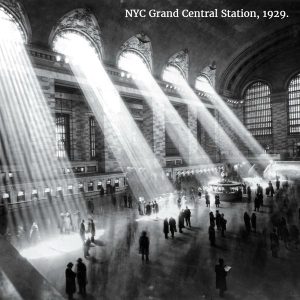

‘Sun can no longer shine through these windows because taller buildings now surround it.’ -History Lovers Club

‘…feelings that defy language.’

‘If a man has to be pleasing to me, conforming, reassuring, before I can love him, then I cannot truly love him. Not that love cannot console or reassure! But if I demand first to be reassured, I will never dare to begin loving. If a man has to be a Jew or a Christian before I can love him, then I cannot love him. If he has to be black or white before I can love him, then I cannot love him. If he has to belong to my political party or social group before I can love him, if he has to wear any kind of uniform, then my love is no longer love because it is not free: it is dictated by something outside itself. It is dominated by an appetite other than love. I love not the person but his classification, and in that event I love him not as a person but as a thing. In this way I remain at the mercy of forces outside myself, and those who seem to me to be neighbors are indeed strangers; for I am, first of all, a stranger to myself.’

-Thomas Merton, Seasons of Celebration, 1965

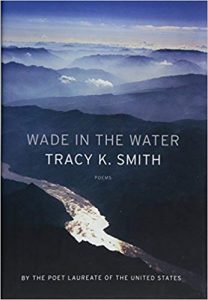

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Tracy K. Smith on the purpose and power of poetry

The two-time American poet laureate joins The Ezra Klein Show for a powerful conversation on love, language, and more.

Ezra Klein:

‘It’s the rare podcast conversation on The Ezra Klein Show where, as it’s happening, I’m making notes to go back and listen again so I can fully absorb what I heard. But this is that kind of episode.

Tracy K. Smith is the chair of the Lewis Center for the Arts at Princeton and a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, and was the two-time poet laureate of the United States from 2017 to 2019. But I’ll be honest: she was an intimidating interview for me. I often find myself frustrated by poetry, yearning for it to simply tell me what it wants to say, aggravated that I can’t seem to crack its code.

Preparing for this conversation, and even more so, talking to Smith, was a revelation. Poetry, she argues, is about expressing “the feelings that defy language.” The struggle is part of the point: you’re going where language stumbles, where literalism fails. Developing a comfort and ease in those spaces isn’t something we’re taught to do, but it’s something we need to do. And so, on one level, this conversation is simply about poetry: what it is, what it does, how to read it.

But on another level, this conversation is also about the ideas and tensions that Smith uses poetry to capture: what it means to be a descendent of slaves, a human in love, a nation divided. Laced through our conversation is readings of poems from her most recent book Wade in the Water, and discussions of some of the hardest questions in the American, and even human, canon. Hearing Smith read her erasure poem, “Declaration” is, without doubt, one of the most powerful moments I’ve had on the podcast.

There is more to this conversation than I can capture here, but to say it simply: this isn’t one to miss, and that’s particularly true if, like me, poetry intimidates you.’

❀

I want to utter you. I want to portray you

not with lapis or gold, but with colors made of apple bark.

There is no image I could invent

that your presence would not eclipse.

-Rilke

Imperative: research for-profit institutions.

February 25, 2020From historian and writer Dr. Megan Kate Nelson:

As the PhD program admissions season is upon us, here’s my totally unsolicited advice!

Unless you have a trust fund:

– Do not accept the invitation of any PhD program that does not give you full funding.

– If no program offers you full funding, do not go to graduate school.

My argument is that prospective students should only enroll in programs that value them enough to give them full funding – so that all PhDs come out of those programs without debt. This should equalize risk for graduating PhDs, regardless of their socio-economic status going in.

If you don’t care about all that and are fine with taking on big debt with slim chances of a job on the other side, then okay. Go ahead. Most PhD programs clearly won’t stop you – which is profoundly unethical in my view, but that’s a provocative tweet for another day.

#Truth

The feminine collective.

AP PHOTOS: A corps of women covering the Weinstein trial

AXIOS/AP

Corps of women covered Weinstein trial … Much of what the world has seen and heard about Weinstein’s rape trial came from women journalists — the regulars at the Manhattan courthouse who would be there reporting regardless of whether a celebrity was involved.

They’ve put their natural journalistic competitiveness aside to go through their notes to ensure they’re accurately quoting testimony, despite the courtroom’s shoddy sound system and the constant wail of sirens outside.

AP’s Mary Altaffer writes:

‘Much of what the world has seen and heard about Harvey Weinstein’s rape trial has come from a core group of women journalists — the regulars at the Manhattan courthouse who would be there reporting regardless of whether a celebrity was involved.

Down in the cramped press room, they’ve squeezed together to offer other reporters a place to work.

They’ve put their natural journalistic competitiveness aside to go through their notes to ensure they’re accurately quoting testimony, despite the courtroom’s shoddy sound system and the constant wail of sirens outside.

Laptops in hand, they’ve repeatedly made the trek from the courthouse gallery to the hallway to file breaking news updates. During lulls, they’ve turned the adjacent women’s bathroom into a lounge and a news bureau, making calls, jotting notes and taking time for themselves to recharge.’

Shrove Tuesday

☆☆¸.•*¨*•☆☆•*¨*•.¸¸☆☆Mardi Gras!☆☆¸.•*¨*•☆☆•*¨*•.¸¸☆☆

The word shrove is a form of the English word shrive, which means to obtain absolution for one’s sins by way of Confession and doing penance. Shrove Tuesday was named after the custom of Christians to be “shriven” before the start of Lent.

Pancakes were traditionally eaten on the day before Ash Wednesday because they were a way to use up eggs, milk, and sugar before the fasting season of the 40 days of Lent. … Many people “give something up” during Lent as a way to prepare for Easter.

Warren gets it. Love, women, and intersectionality.

February 24, 2020‘I love my country, I love it very much. It is for that reason I do not makes excuses for it. If we think installing a hero is going to solve our problems, here is my warning now.

It won’t.

We NEED to BE the hero we seek in elected officials. Or else round and round we go.’

~Deina @sapereaude86

‘Political discourse is my Assignment. America is my Station. Love is my Religion’

‘Throughout her campaign, Warren has shown her ability to use intersectional approaches to analyze a wide variety of social ills & her engagement with this paradigm has only gotten richer as her campaign has progressed.’ By far, the best candidate for president.

Elizabeth Warren Is Running an Unapologetically Intersectional Campaign

As much as I want Medicare for All and for the rich to pay higher taxes, that won’t cure sexism. Warren gets that.

Another lesson of intersectionality has to do less with analysis and theory than with what we may call a politics of respectful attention. Taking intersectionality seriously means moving beyond merely acknowledging one’s own privilege and understanding that walking the walk entails listening to and learning from those who live in identities different from your own. Warren has exhibited this repeatedly, chiding other Democrats for only engaging with the black community during election time. Conversely, she met with Ta-Nehisi Coates—years before she became a presidential candidate—to learn from him following his explosive writing on reparations.

As Nelini Stamp writes in the newly radical Teen Vogue, “Elizabeth Warren is paying attention…. Her [environmental justice] plan is informed by the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice, an equity-based framework written by activists of color in 1991 that no presidential administration has acted on to date. Not anymore. Warren centers marginalized communities again and again in her plan.” And when Warren reads off the names of murdered trans women (not at a LGBTQ event!) and pledges to do so every year in the Rose Garden, she “brings the margin to the center” as bell hooks put it, making visible the ways in which race, class, gender, sexuality live in particular bodies in particular ways.

Being intersectional also means having to own up to mistakes, learn from those who live and love differently from you, step aside when necessary and step up when the situation dictates it. At a presidential forum on Native American issues in August, Warren addressed her own errors. “Like anyone who’s being honest with themselves, I know that I have made mistakes,” said Warren, presumably referring to her release of a DNA test purporting to show that she had Native American ancestry. “I am sorry for harm I have caused. I have listened and I have learned a lot, and I am grateful for the many conversations that we’ve had together.”

The key to robust intersectional thinking is to concretely demonstrate the ways in which things that seem to be about one concern are often inflected through others.

§ As Warren herself said in a tweet outlining her disability rights platform, “All policy issues are disability policy issues, which is why I’ve approached many of my previous plans with a disability rights lens, from criminal justice reform to ensuring a high-quality public education for all, to strengthening our democracy.”

§ When Warren addresses the debate about guns and links it to domestic violence, she is signifying precisely how a different angle of vision illuminates the connection between a culture of unfettered access to guns and a culture of violence against women.

§ During the New Hampshire debate, as the candidates discussed racial inequities in criminal justice and in wealth acquisition, Warren pointed out how her proposal to levy a wealth tax is not a simple “class” issue but in fact would address racial inequality in substantive ways by, for example, getting rid of student debt that unduly burdens people of color, who tend to be more in debt and take longer to pay it back.

§ On abortion, Warren made sure to point out the class and race dimensions, stating that if Roe v. Wade gets overturned, the rich (who are largely white) will continue to have access to reproductive services, while poor women and women of color will suffer.

§ She pivoted to condemn our history of discriminatory housing practices and make the point about the various ways in which racism informs pretty much everything, insisting that we can’t relegate “race” questions to some narrow aperture of vision.

§ In her plan on “Valuing the Work of Women of Color” (yes, she actually has a plan for that—a claim no other candidate can make), Warren acknowledges how the interplay of sexual and gender identities (as well as ability) with racial identities can exacerbate the obstacles women of color face.

§ In her plan on securing LGBTQ equality she highlights the connections between LGBTQ oppression and homelessness and increased risk of incarceration.

§ When discussing how to honor and empower Native people, she points out the centrality of anti-violence work for indigenous women who often go unprotected due to conflicts of tribal and federal governance.

[full read]

https://www.thenation.com/article/politics/elizabeth-warren-intersectional-campaign/

In lieu of SNL debate recap. #TikTok

https://t.co/eUMOKQ2xcEhttps://twitter.com/theferocity/status/1231936042346983424?s=20

Comment est-ce possible?

February 22, 202040 years.

“Knowing the difference between when people are using you and when people truly care about you, that’s what ‘Against the Wind’ is all about.”

-Bob Seger, 1980 [Rolling Stone]

Against the Wind is Seger’s only Number One album.

Compassion, love and truth.

‘Human nature is not evil. All pleasure is not wrong. All spontaneous desires not selfish. The doctrine of original sin does not mean that human nature has been completely corrupted and that man’s freedom is always inclined to sin.

Man is neither a devil nor an angel. He is not pure spirit, but a being of flesh and spirit, subject to error and malice, but basically inclined to seek truth and goodness. He is, indeed, a sinner: but their hearts respond to love and grace. It also responds to the goodness and to the need of his fellowman.’

-Thomas Merton, Life and Holiness [1963]

If we over-use the intellectual center, then our work lies in bringing the emotional and moving centers fully online and integrating them. Wisdom is a way of knowing that goes beyond one’s mind, one’s rational understanding, and embraces the whole of a person: mind, heart, and body. These three centers must all be working, and working in harmony, as the first prerequisite to the Wisdom way of knowing.

—Cynthia Bourgeault

This essay is excerpted from W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea,

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon droop and the last tide fail,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail,

As the water all night long is crying to me.

— Arthur Symons

“Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or, I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card,—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain suddenness that I was different from the others; or like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination-time, or beat them at a foot-race, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the years all this fine contempt began to fade; for the worlds I longed for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head,—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white; or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian,

the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

One ever feels his two-ness,—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife,—this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten.

The shadow of a mighty Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to lose effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness,—it is the contradiction of double aims. The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand to escape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart in either cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister or doctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of another people. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of ten thousand thousand people,—has sent them often wooing false gods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faith as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to a promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came,—suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood and passion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

“Shout, O children!

Shout, you’re free!

For God has bought your liberty!”

Years have passed away since then,—ten, twenty, forty; forty years of national life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthy spectre sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation’s feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastest social problem:—

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!”The Nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people,—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp,—like a tantalizing will-o’-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host.

The holocaust of war, the terrors of the Ku-Klux Klan, the lies of carpet-baggers, the disorganization of industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he now regarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which war had partially endowed him.

And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal to vote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dream of political power,—a powerful movement, the rise of another ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after a clouded day. It was the ideal of “book-learning”; the curiosity, born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway of Emancipation and law, steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here and there a foot had slipped or some one had fallen. To the tired climbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting-place, little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In those sombre forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself,—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that dead-weight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully count his bastards and his prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling, sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Men call the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the natural defence of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance, purity against crime, the “higher” against the “lower” races. To which the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to so much of this strange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization, culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meekly does obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leaps beyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nigh speechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, the ridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact and wanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and the boisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything black, from Toussaint to the devil,—before this there rises a sickening despair that would disarm and discourage any nation save that black host to whom “discouragement” is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came borne upon the four winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the black man’s ballot, by force or fraud,—and behold the suicide of a race! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something of good,—the more careful adjustment of education to real life, the clearer perception of the Negroes’ social responsibilities, and the sobering realization of the meaning of progress.

So dawned the time of Sturm und Drang: storm and stress to-day rocks our little boat on the mad waters of the world-sea; there is within and without the sound of conflict, the burning of body and rending of soul; inspiration strives with doubt, and faith with vain questionings. The bright ideals of the past,—physical freedom, political power, the training of brains and the training of hands,—all these in turn have waxed and waned, until even the last grows dim and overcast. Are they all wrong,—all false? No, not that, but each alone was over-simple and incomplete,—the dreams of a credulous race-childhood, or the fond imaginings of the other world which does not know and does not want to know our power. To be really true, all these ideals must be melted and welded into one. The training of the schools we need to-day more than ever,—the training of deft hands, quick eyes and ears, and above all the broader, deeper, higher culture of gifted minds and pure hearts. The power of the ballot we need in sheer self-defence,—else what shall save us from a second slavery? Freedom, too, the long-sought, we still seek,—the freedom of life and limb, the freedom to work and think, the freedom to love and aspire.

Work, culture, liberty,—all these we need, not singly but together, not successively but together, each growing and aiding each, and all striving toward that vaster ideal that swims before the Negro people, the ideal of human brotherhood, gained through the unifying ideal of Race; the ideal of fostering and developing the traits and talents of the Negro, not in opposition to or contempt for other races, but rather in large conformity to the greater ideals of the American Republic, in order that some day on American soil two world-races may give each to each those characteristics both so sadly lack.

We the darker ones come even now not altogether empty-handed: there are to-day no truer exponents of the pure human spirit of the Declaration of Independence than the American Negroes; there is no true American music but the wild sweet melodies of the Negro slave; the American fairy tales and folk-lore are Indian and African; and, all in all, we black men seem the sole oasis of simple faith and reverence in a dusty desert of dollars and smartness. Will America be poorer if she replace her brutal dyspeptic blundering with light-hearted but determined Negro humility? or her coarse and cruel wit with loving jovial good-humor? or her vulgar music with the soul of the Sorrow Songs?

Merely a concrete test of the underlying principles of the great republic is the Negro Problem, and the spiritual striving of the freedmen’s sons is the travail of souls whose burden is almost beyond the measure of their strength, but who bear it in the name of an historic race, in the name of this the land of their fathers’ fathers, and in the name of human opportunity.

And now what I have briefly sketched in large outline let me on coming pages tell again in many ways, with loving emphasis and deeper detail, that men may listen to the striving in the souls of black folk.”

Maya Angelou, Elizabeth Alexander, and Arnold Rampersad — W.E.B. Du Bois and the American Soul

As Rebecca Solnit explains, hope is “coming to terms with the fact that we don’t know what will happen and that there’s maybe room for us to intervene, and that we have to let go of the certainty people seem to love more than hope and know that we don’t know what’s going to happen.” To practice hope as Solnit describes it requires acknowledging a similar incompleteness to the one that Consolmagno speaks about.

Perhaps embracing the inherent incompleteness of what we know of the world is a form of hope, allowing us to remember that there’s always something left to unfold or be discovered — and not always in the way we might’ve been conditioned to expect it. May we allow ourselves to listen, and even delight in its surprises, as we work alongside the richness of this incompleteness.

Fr. Richard Rohr, Center for Action & Contemplation:

‘The good, the true, and the beautiful are their own best argument for themselves, by themselves, and in themselves. Such deep inner knowing evokes the soul and pulls the soul into All Oneness. Incarnation is beauty, and beauty needs to be incarnate—that is specific, concrete, particular. We need to experience very particular, soul-evoking goodness in order to be shaken into what many call “realization.” It is often a momentary shock where we know we have been moved to a different plane of awareness.’

2.21.1965

February 21, 2020El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, Malcolm X, a Muslim minister and human rights activist, was assassinated on this day 55 years ago.

#2020

February 20, 2020A woman can work hard,

And succeed

And we could be content,

To believe

That she could be in charge of the free,

And be the president

If not today, then

What happens tomorrow?

❀

If I Look hard enough

I will see

That there can be enough

And I believe

I can think clear enough,

To conceive

A place where there’s enough

❀

That we are waking up,

From a spell

That those that profit from the fear,

Cast so well.

And good people of the earth,

Now can tell,

~Melissa

Cat.

‘Grief is heavy with sadness and tears

Great is the noise from the earth and the seas

O love! O love! Be with us always.’ -Yusuf Islam

What could better look like?

One thing leads to another.

-Judge J. Edward Lumbard

❦

America is not some finished work or failed project but an ongoing experiment.

If parts of the machine are broken, then the responsibility of citizens is to fix the machine, not throw it away.

Our imperfections can, and out to, draw us together in humility, realism, patience, and determination.

No one has a monopoly on wisdom or is free from error. Everyone benefits from understanding other points of view.

The foundational virtue of democracy is trust, not trust in one’s own rectitude or opinion, but rust in the capacity of collective deliberation to move us forward.

To often we define our real national challenges–climate change, immigration, health care, guns–in a way that guarantees division into warring camps.

Instead we should be asking one another: What could “better” look like?

Our Founders thought in centuries.

Abraham Lincoln warned that the greater danger to the nation came from within. All the armies of the world could not crush us, he maintained, but we could still “die by suicide.”

-James Mattis, a former secretary of defense who served for more than four decades as a Marine infantry officer.

George Washington:

“Sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns disposition to the purposes of his own elevation on the ruins of public liberty.”

If we want our democracy to succeed, indeed, if we want the idea of democracy to regain respect in an age when dissatisfaction with democracies is rising, we’ll need to understand the many ways in which today’s [various] platforms create conditions that may be hostile to democracy’s success. And then we’ll have to take decisive action to improve.

-Social Psychologist Jonathan Haidt and technoethicist Tobias Rose-Stockwell

Tikkun Olam

February 19, 2020Hebrew: תיקון עולם

Translation: The Repair of the World

‘If you see what needs to be repaired and how to repair it, then you have found a piece of the world that God has left for you to complete. But if you only see what is wrong and what is ugly in the world, then it is you yourself that needs repair.’

[Jews today have extended this classical concept to include the pursuit of social justice and care for the environment.]

When will it be enough?

The Rush to Write Off Elizabeth Warren Is Making the Hillary Generation Furious

Progressive women feel they are being erased from the Democratic presidential primary

Should Elizabeth Warren drop out? On one level, it’s a natural question to ask after the one-time Democratic front-runner finished in a disappointing third place in the Iowa caucuses and fourth in her neighboring state of New Hampshire. In presidential politics, few candidates — male or female — ever survive the harsh consequences of underperforming.

On another level, the sentiment is utterly oblivious to the fury and hurt bubbling up among the millions of women who have supported Warren’s campaign. Three years after Hillary Clinton lost to Donald Trump,

the political class seems dangerously out of touch with women’s broiling resentment over the sense that being smart and competent won’t ever be enough.

I have spent many hours over the past three years interviewing, as part of a book project, a group of women who met as freshmen at the University of Michigan in the mid-1960s. Like many of their baby boomer peers, these women watched as men with equivalent levels of education — in some cases their own spouses — out-achieved and out-earned them. They straddled career and family obligations, exhausting themselves on the infamous “second shift” while husbands and male colleagues fired up the grill on summer weekends and then gave themselves the rest of the year off domestic duties.

For many of these women, electing Hillary Clinton was supposed to be a form of validation — a final, irrefutable sign that as complicated and frustrating and sometimes disillusioning as their adult lives had been, the general trajectory was toward progress.

But with Clinton’s defeat to a man most of them regarded as her intellectual and professional inferior, these women and their peers faced a pair of startling revelations. They might not live to see a woman elected president of their country. And the progress they had taken for granted might be reversible — or, worse, an illusion.

It’s enough to make a woman livid. Indeed, as the Democratic presidential primaries hurtle toward Super Tuesday with the once-formidable candidacy of Kamala Harris already ended and Elizabeth Warren all but forgotten by most of the press corps, thousands — perhaps even millions — of progressive women are surprising themselves with the depth of their pain and rage. They will not be erased. They are being erased.

Electing Hillary Clinton was supposed to be a form of validation — a sign that as frustrating and disillusioning as their adult lives had been, the general trajectory was toward progress.

It is an accumulation of outrages. Hillary Clinton reappears after the election to write a memoir and give speeches, and the Crooked Media bros want to know why she won’t just go away. Christine Blasey Ford endures death threats to testify against Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination, and is greeted by skepticism, mockery, and Kavanaugh’s own incandescent rage over having his nomination besmirched. Kamala Harris is dismissed as too angry after she takes on that nice old former vice president. Kirsten Gillibrand is branded a traitor for taking down Al Franken. Elizabeth Warren’s political obituary is written after all of two primary contests. And on it goes.

The profound well of anger is by no means limited to white baby boomer women. Younger counterparts talk about “2016 PTSD” or report that they’ve been “rage donating,” as the act of making angry political contributions has been dubbed in the age of Trump. But it is perhaps most intense among boomers, in part because many of them are now looking back at their lives through the lens of the last presidential election.

One of the most naturally optimistic of the baby boomer women I’ve been following is a woman named Linda, who recently retired after a long career as a pediatrician. When we spoke a few months after the 2016 election, she was disconsolate. “All the advances we thought happened and were secured, they were just gone,” she said.

To Linda’s mind, the outcome represented nothing less than the erasure of her entire generation, the women who came of age during the first blush of feminism and who had anticipated a Clinton victory as the validation of their own choices and sacrifices. She thought of her own struggle through medical school at a time when there were no locker rooms for female doctors, of the oncology career she gave up for her ex-husband, of the decades spent raising four children on her own.

The year before Linda and her classmates graduated from college, only about 30% of women her age expected to be working at age 35 — roughly the same percentage whose mothers worked. Five years later, the percentage of women in their late teens and early twenties who expected to be working at age 35 had nearly doubled. Their expectations about what their futures would bring had escalated faster than at any point in history, leading to what the economic historian Claudia Goldin has described as a social revolution.

For a while, reality played along. Women graduated from college and professional schools at increasing rates, and flooded the workforce.

But reality did not, in the end, deliver. By the mid-1990s, all the charts and graphs that had looked so promising in previous decades had begun to flatten, and in some cases even retreat. Today, fewer than 20% of partners at the top 200 law firms are women, even though law schools have been graduating roughly equal numbers of men and women for several decades. Fewer than 10% of Fortune 500 chief executives are women, even though more than 40% of business school graduates since the 1990s have been women.

The past three years have been a roller coaster ride for Linda’s generation. Though painfully wise to the ways that harassment and discrimination had stalled their own career prospects and weighed on their psyches, they were not prepared for the avalanche of testimony about routine assault and misogyny shared after revelations about the likes of Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer, and Les Moonves. The scale of it — the persistence of it — was shattering.

At the same time, the 2018 midterm victories for progressives were the result of women turning their grief and anger into activism, swamping campaign offices and maxing out donation limits with whatever they could spare. They ran for office in record numbers, too, winning a record number of seats in Congress. Women powered the resistance in suburban communities across the country, and turned an organization like Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America into a force that has gun rights activists back on their heels for the first time in decades. By the summer of 2019, there appeared to be an embarrassment of riches, with not just one, but five women running for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Now it’s very possible that none of them will end up facing Donald Trump in November. If that happens, this presidential cycle will have shown that even rage comes with a double standard attached. It can put a pampered former reality television star in the White House. But it can’t vault an eminently qualified woman like Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris to the top of a ticket.

Democratic operatives counting on millions of highly energized women to power their nominee across the finish line 2018-style would be advised to take notice of this. The stage of grief that typically follows anger is… depression.

https://gen.medium.com/amp/p/5feebe8b36ac

#Election2020

Pay attention.

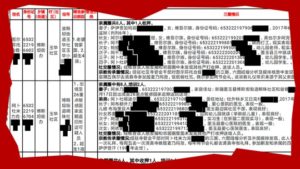

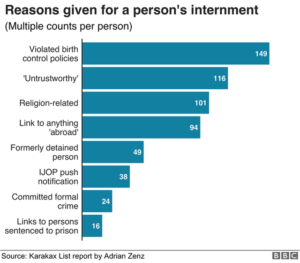

February 18, 2020The painstaking records – made up of 137 pages of columns and rows – include how often people pray, how they dress, whom they contact and how their family members behave.

China Uighurs: Detained for beards, veils and internet browsing

BBC

- Veils

- Beards

- Passport Applications

- Guilt by Association

- Family Members’ Travel

- Friends Visited

- Home Religious Atmospheres

- How Often They Prayed

- Islamic Political Leanings

- Violating China’s Strict Family Planning Laws

- Organizing Religious Study Groups

“It reveals the witch-hunt-like mindset that has been and continues to dominate social life in the region,” he said.

In early 2017, when the internment campaign began in earnest, groups of loyal Communist Party workers, known as “village-based work teams”, began to rake through Uighur society with a massive dragnet.

For every main individual, the 11th column of the spreadsheet is used to record their family relationships and their social circle.

China has long defended its actions in Xinjiang as part of an urgent response to the threat of extremism and terrorism.

[full read]

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51520622

[It’s imperative U.S. citizens be aware of this country’s language used by political leaders, pundits, and media. Be diligent. Pay attention. Think of the human rights violations already being afflicted and the reasons given. Use this report from the BBC as a transparency for not only China, but other countries as well. Political theorist Hannah Arendt writing about totalitarian leaders of the 20th century: they instilled in their followers a mixture of gullibility and cynicism…the onslaught of propaganda conditioned people to believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true. -dayle]

The Power of the Dot

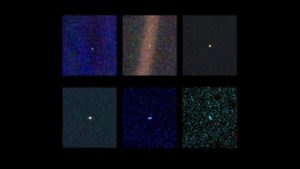

The Power of the ‘Pale Blue Dot’ Three Decades Later

The spacecraft that captured the famous, fuzzy photo grows weaker each year, but the image still soothes.

Marina Koren

The Atlantic

I emailed Amanda, who lives in Berlin now, to ask her why she decided to get the tattoo; she’d told me it was meaningful for her the day she got it, but I couldn’t remember the specifics. “I wanted to have a permanent reminder of how small my daily problems and heartbreaks were in the scheme of the universe,” she said. “I wanted to be able to look down and think, Oh yeah, none of this matters, so just try to be kind and grateful and enjoy yourself.”

Carl Sagan:

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there—on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

It is a lovely perspective, this view of outer space as salve, and it could be quite effective; after all, there’s no bigger picture than the entire universe. But more often, especially these days, I’ve heard a darker interpretation of our smallness in the face of celestial forces. A small corner of the internet invokes the workings of the cosmos as a way of dismissing depressing headlines here on Earth. Yes, everything is awful, such people half-joke, but who cares? We’re all going to perish during the heat death of the universe, anyway. Didn’t you hear our sun will collapse in on itself in less than 5 billion years? Or that the Milky Way is expected to collide with another galaxy even sooner?

At the risk of sounding too earnest—but what else are anniversaries for?—I hope “Pale Blue Dot” inspires the opposite. Believing that one-10th of a pixel on a screen is going to bring people comfort is foolish, of course. But it’s something.

[full read]

#ConsiderElizabeth

February 17, 2020“I was proud to fight beside Senator Reid and Barack Obama and to protect consumers—and I’ll keep fighting to protect consumers as president of the United States. Watch our new ad airing in Nevada now.”

[Follow the link to view :30 ad running in Nevada.]