Stay.

June 10, 2018None of us can truly know what we mean to other people, and none of us can know what our future self will experience. As a scholar, Jennifer Michael Hecht proposes a new cultural reckoning with suicide, based not on morality or on rights but on our essential need for each other. “Look how involved we all are just under the surface, and let’s try to help each other.” The communitarian is what struck me first.

We’re in it together in this profound way, and you can take some strength from that. I think that’s, for me, that’s been very important. Just feel like, obviously we’re not individuals. Wow, how could I have thought that we were on that kind of level? And it’s funny, because my two arguments, that you owe it to other people and that you owe it to your future self, are both about looking at what the individual means. Because when you look at a person within a group, and all the trends we follow, the clothes, the car, the not-car, all these trends that we follow, you realize the extent to which we’re enmeshed. And when you look at yourself and realize that you have fallen in and out of love with the same person, you have fought with friends thinking you’ll never speak to them again, and then you love them again.

It’s a great idea to write yourself a note saying, “I am happy right now despite previous depressions. Please do not do anything to inhibit this from happening again.” And go read it when you’re down. There it is in your handwriting.Remind your mood that the other mood exists. Because depression’s particularly — one of its definitions is that within depression you can’t see that you’ve ever not been depressed.

It’s impulsive. It’s tremendously impulsive. And that if you can get past the impulse, and if you can put a conceptual barrier in your head, that it can work in the same way that that chain link fence can. You just — you’ve put up a barrier. You’ve talked to yourself about this. And don’t argue with yourself. Get in bed and feel terrible, or go get help, or, jeez, playing a video game sometimes takes my mind off misery. There’s ways to get through the worst, and, really, when I’m starting out, what I’m starting out with is really just the idea of, yeah, sometimes life, for some of us, can be unbelievably painful. But don’t do this one thing. Your well-being is important to other people.

Choose to stay alive.

https://onbeing.org/programs/jennifer-michael-hecht-suicide-and-hope-for-our-future-selves/

This past week reminded me that I need to be kinder. I never know what someone who is going through or why they are feeling the way that they do.

Oh, Infinite Creator, hold us softly in your great love. Remind us that your light connects us to all people and all things–the light alive in each of us. May we remember that we’re here on purpose, created to shine the light of love, peace and joy in our own way. Today, may we know the truth of our being and live from that knowing. -Science of Mind

What should you do when a loved one is severely depressed? Don’t underestimate the power of showing up.

YOU ARE SO LOVED AND WE LIKE HAVING YOU AROUND. *ties one end of this sentence to your heart, the other end to everyone who loves you in this life, even if clouds obscure your view *checks knots* THERE. STAY PUT, YOU. TUG IF YOU NEED ANYTHING. -LIN-MANUEL MIRANDA

• • • •

You may not feel that your presence is wanted. But just being by the side of someone who is depressed, and reminding her that she is special to you, is important to ensuring that she does not feel alone. It’s OK to ask if she’s having suicidal thoughts.

Lots of people struggle with depression without ever considering suicide. But depression is often a factor. Although you may worry that asking, “Are you thinking about killing yourself?” will insult someone you’re trying to help — or worse, encourage her to go in that direction — experts say the opposite is true.

“It’s important to know you can’t trigger suicidal thinking just by asking about it.”

If the answer is yes, it’s crucial that you calmly ask when and how; it’s much easier to help prevent a friend from hurting herself if you know the specifics.

In some cases, calling 911 may be the best option. If you do, ask for a crisis intervention team, Mr. Doederlein urged.

But remember that interactions with law enforcement can vary wildly, depending on race and socio-economic background. In cases where you’re concerned that calling police could put a person in danger, try to come up with an alternate plan in advance.

-Heather Murphy

• • • •

Check on your strong friends.

Check on your quiet friends.

Check on your “happy” friends.

Check on your creative friends.

Check on each other.

-Lauren Warren

• • • •

CDC/NPR

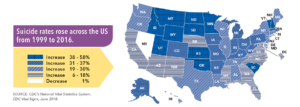

Suicide rates have increased in nearly every state over the past two decades, and half of the states have seen suicide rates go up more than 30 percent.

The rise in suicide rates was highest in the central, northern region of the U.S., with North Dakota, for example, seeing a 57.6 percent increase since 1999.

On average, there are 123 suicides per day in the United States.

We often assume that people who commit suicide are mentally ill, but this isn’t always the case. There are many factors that can contribute to suicide that have nothing to do with mental illness, including loss of a relationship, loneliness, chronic illness, financial loss, history of trauma or abuse and the stigma associated with asking for help.

• • • •

But why are so many more Americans getting to this level of emotional despair than in the past? As journalist Johann Hari wrote in his best-selling book Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression — and the Unexpected Solutions, the epidemic of depression and despair in the Western World isn’t always caused by our brains. It’s largely caused by key problems in the way we live.

We exist largely disconnected from our extended families, friends and communities — except in the shallow interactions of social media.

-Kirsten Powers/USA Today

• • • •

Scott Simon/Weekend Edition/NPR

“I have to talk in an utterly personal way about suicide. My grandmother took her life, and my mother, who struggled against the impulse several times, said, “Suicide puts a fly in your head. It’s always in there, buzzing around.

It is risky to make generalizations about suicide — whether it appears to have been triggered by depression, job loss, sickness, romance, drink or drugs. The person who takes their life may feel alone and isolated. But they leave behind those who love them and who are left to wrestle with sleepless regrets and ceaseless wondering.

Harvard Business Review

Research in 2013 from demographer Richelle Winkler shows that in the U.S., age segregation is often as ingrained as racial segregation. Using census data from 1990 to 2010, Winkler found that in some parts of the country, old (age 60+) and young (age 20–34) are roughly as segregated as Hispanics and whites. This broader pattern is reflected in our neighborhoods. A 2011 study from MetLife and the National Association of Homebuilders found that nearly one-third of people over the age of 55 live in communities that entirely or mostly comprise people 55 and older.

“I think we’re in the midst of a dangerous experiment,” Cornell University professor Karl Pillemer told The Huffington Post. “This is the most age-segregated society that’s ever been. Vast numbers of younger people are likely to live into their 90s without contact with older people. As a result, young people’s view of aging is highly unrealistic and absurd.”

The extent of the isolation, of course, runs both ways — especially when it comes to young and old who aren’t related.

An array of other housing innovators, aging experts, architects, and homebuilders — including developers of senior-only communities — are contributing to the trend.

And now some of the biggest homebuilders are getting into the act. Lennar is promoting its NextGen Model, which includes space for families and “aging parents, live-in caretakers, post-college grown children, and more” under one roof, with privacy intact. Pardee Homes, another big builder, has launched GenSmart Suite to create homes designed to allow multiple generations to live together. While these efforts are usually discussed in terms of an expanded notion of family, they nonetheless contribute to the creation of multigenerational neighborhoods.

It makes sense that this innovation is beginning to happen now, as we reach an important demographic turning point. For the first time ever, there are more Americans over 50 than under 18. These numbers create both opportunity and urgency for making the most of the multigenerational reality that’s already here and that’s only projected to grow. And they force us to redefine what it means to be efficient — and human.

• • • •

Pain is often a sign that something has to change.

Our hears and bodies often give us messages we fail to pay attention to. Ironically, we are all so aware of pain, can hardly ignore it, but we rarely hear what it has to say.

It is true that we may need to withstand great pain, great heartache, great disappointment and loss in order to unfold into the rest of our lives. But our pain may also be showing us exactly where we need to change.

Try to let the pain move through you.

-Mark Nepo

Always remember: ‘Your well-being is important to other people. Choose to stay alive. We have need for each other.’