Seth Godin

The Candy Diet

If we don’t care to learn more, we won’t spend time or resources on knowledge.

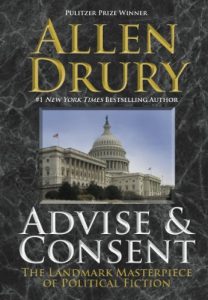

“The bestselling novel of 1961 was Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent. Millions of people read this 690-page political novel.

In 2016, the big sellers were coloring books.

Fifteen years ago, cable channels like TLC (the “L” stood for Learning), Bravo and the History Channel (the “History” stood for History) promised to add texture and information to the blighted TV landscape. Now these networks run shows about marrying people based on how well they kiss.

And of course, newspapers won Pulitzer prizes for telling us things we didn’t want to hear. We’ve responded by not buying newspapers any more.

The decline of thoughtful media has been discussed for a century. This is not new. What is new: A fundamental shift not just in the profit-seeking gatekeepers, but in the culture as a whole.

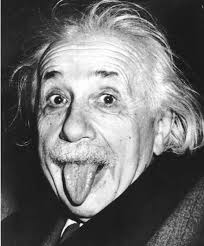

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”*

[*Ironically, this isn’t what Einstein actually said. It was this, “It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” Alas, I’ve been seduced into believing that the shorter one now works better.]

Is it possible we’ve made things simpler than they ought to be, and established non-curiosity as the new standard?

We are certainly guilty of being active participants in a media landscape that breaks Einstein’s simplicity law every day. And having gotten away with it so far, we’re now considering removing the law from our memory.

The economics seem to be that the only way to make a living is to reach a lot of people and the only way to reach a lot of people is to race to the bottom, seek out quick clicks, make it easy to swallow, reinforce existing beliefs, keep it short, make it sort of fun, or prurient, or urgent, and most of all, dumb it down.

And that’s the true danger of anti-intellectualism. While it’s foolish to choose to be stupid, it’s cultural suicide to decide that insights, theories and truth don’t actually matter. If we don’t care to learn more, we won’t spend time or resources on knowledge.

We can survive if we eat candy for an entire day, but if we put the greenmarkets out of business along the way, all that’s left is candy.

Give your kid a tablet, a game, and some chicken fingers for dinner. It’s easier than talking to him.

Read the short articles, the ones with pictures, it’s simpler than digging deep.

Clickbait works for a reason. Because people click on it.

The thing about clickbait, though, is that it exists to catch prey, not to inform them. It’s bait, after all.

The good news: We don’t need many people to demand more from the media before the media responds. The Beverly Hillbillies were a popular show, but that didn’t stop Star Trek from having a shot at improving the culture.

The media has always bounced between pandering to make a buck and upping the intellectual ante of what they present. Now that this balance has been ceded to an algorithm, we’re on the edge of a breakneck race to the bottom, with no brakes and no break in sight.

Vote with your clicks, with your sponsorship, with your bookstore dollars. Vote with your conversations, with your letters to the editor, by changing the channel…

Even if only a few people use precise words, employ thoughtful reasoning and ask difficult questions, it still forces those around them to catch up. It’s easy to imagine a slippery slope down, but there’s also the cultural ratchet, a positive function in which people race to learn more and understand more so they can keep up with those around them.

Turn the ratchet. We can lead our way back to curiosity, inquiry and discovery if we (just a few for now) measure the right things and refuse the easy option in favor of insisting on better.”

Leave a Reply