church

❥ this.

February 7, 2020If God Is Dead, Your Time Is Everything

Martin Hägglund argues that rigorous secularism leads to socialism.

Hägglund reminds us that King had studied Marx with care while a student, and that he told the Montgomery Advertiser, in 1956, that his favorite philosopher was Hegel. Toward the end of his life, King had begun to insist that society has to “question the capitalistic economy.” He called for what he described as “a revolution of values.” At a tape-recorded staff meeting for the Poor People’s Campaign in January, 1968, King appears to have asked for the recording to be stopped, so that he could talk candidly about the fact that, in the words of a witness, “he didn’t believe capitalism as it was constructed could meet the needs of poor people, and that what we might need to look at was a kind of socialism, but a democratic form of socialism.” King told the group that if anyone made that information public he would deny it.

Hägglund does his usual deconstructive reversal, and argues that King’s religiosity was really a committed secularism. At this point in the book, this looks less like a hermeneutic move than like an expected reality. We read the famous words of King’s last speech with new eyes, alert both to his secularism and to a burgeoning critique of capitalism that had to stay clandestine:

It’s all right to talk about “streets flowing with milk and honey,” but God has commanded us to be concerned about the slums down here, and his children who can’t eat three square meals a day. It’s all right to talk about the new Jerusalem, but one day, God’s preacher must talk about the new New York, the new Atlanta, the new Philadelphia, the new Los Angeles, the new Memphis, Tennessee. This is what we have to do.

I finished “This Life” in a state of enlightened despair, with clearer vision and cloudier purpose—I was convinced, step by step, of the moral rectitude of Hägglund’s argument even as I struggled to imagine the political system that might institute his desired revaluation of value. As if aware of such faintheartedness, he ends the book with a beautiful examination of Martin Luther King, Jr.—in particular the celebrated last speech he gave, in Memphis. Hägglund reminds us that King had studied Marx with care while a student, and that he told the Montgomery Advertiser, in 1956, that his favorite philosopher was Hegel. Toward the end of his life, King had begun to insist that society has to “question the capitalistic economy.” He called for what he described as “a revolution of values.”

After the theory and the academic reversals and the grand proposals, Hägglund’s book ends, stirringly, with a grounded account of a man who died trying to use his precious time to change the precious time of oppressed people, aware that the full realization of his vision would likely involve a revaluation of value that could not yet be spoken in America. We still haven’t seen that system, and it’s hard to imagine it, but someone went up the mountain and looked out, and saw the promised land. And that land is in this life, not in another one. ♦

[Full Read]

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/05/20/if-god-is-dead-your-time-is-everything

Named a Book of the Year by The Guardian

‘A profound, original, and accessible book that offers a new secular vision of how we can lead our lives. Ranging from fundamental existential questions to the most pressing social issues of our time, This Life shows why our commitment to freedom and democracy should lead us beyond both religion and capitalism.

In this groundbreaking book, the philosopher Martin Hägglund challenges our received notions of faith and freedom. The faith we need to cultivate, he argues, is not a religious faith in eternity but a secular faith devoted to our finite life together.

He shows that all spiritual questions of freedom are inseparable from economic and material conditions. What ultimately matters is how we treat one another in this life, and what we do with our time together.

Hägglund develops new existential and political principles while transforming our understanding of spiritual life. His critique of religion takes us to the heart of what it means to mourn our loved ones, be committed, and care about a sustainable world. His critique of capitalism demonstrates that we fail to sustain our democratic values because our lives depend on wage labor. In clear and pathbreaking terms, Hägglund explains why capitalism is inimical to our freedom, and why we should instead pursue a novel form of democratic socialism.

In developing his vision of an emancipated secular life, Hägglund engages with great philosophers from Aristotle to Hegel and Marx, literary writers from Dante to Proust and Knausgaard, political economists from Mill to Keynes and Hayek, and religious thinkers from Augustine to Kierkegaard and Martin Luther King, Jr. This Life gives us new access to our past—for the sake of a different future.’

‘Here comes everybody.’

June 1, 2019‘We are no longer innocent; but we must make every effort to become primitive so that we can begin again each time, and from our hearts. We must become springtime people in order to find the summer, whose greatness we must herald.’

-Rilke, Early Journals

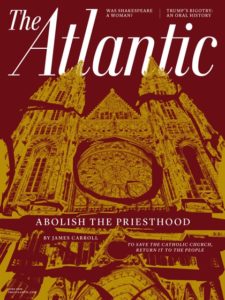

The Atlantic

To Save the Church, Dismantle the Priesthood

Catholics must death themselves from the clerical hierarchy, and take the faith back into their own hands.

James Carroll

As James Joyce wrote in Finnegans Wake, Catholic means “Here Comes Everybody.”

[excerpt]

Replacing the diseased model of the Church with something healthy may involve, for a time, intentional absence from services or life on the margins—less in the pews than in the rearmost shadows. But it will always involve deliberate performance of the works of mercy: feeding the hungry, caring for the poor, visiting the sick, striving for justice. These can be today’s chosen forms of the faith. It will involve, for many, unauthorized expressions of prayer and worship—egalitarian, authentic, ecumenical; having nothing to do with diocesan borders, parish boundaries, or the sacrament of holy orders. That may be especially true in so-called intentional communities that lift up the leadership of women. These already exist, everywhere. No matter who presides at whatever form the altar takes, such adaptations of Eucharistic observance return to the theological essence of the sacrament. Christ is experienced not through the officiant but through the faith of the whole community. “For where two or three are gathered in my name,” Jesus said, “there am I in the midst of them.”

[…]

In what way, one might ask, can such institutional detachment square with actual Catholic identity? Through devotions and prayers and rituals that perpetuate the Catholic tradition in diverse forms, undertaken by a wide range of commonsensical believers, all insisting on the Catholic character of what they are doing. Their ranks would include ad hoc organizers of priestless parishes; parents who band together for the sake of the religious instruction of youngsters; social activists who take on injustice in the name of Jesus; and even social-media wizards launching, say, #ChurchResist. As ever, the Church’s principal organizing event will be the communal experience of the Mass, the structure of which—reading the Word, breaking the bread—will remain universal; it will not need to be celebrated by a member of some sacerdotal caste. The gradual ascendance of lay leaders in the Church is in any case becoming a fact of life, driven by shortages of personnel and expertise. Now is the time to make this ascendance intentional, and to accelerate it. The pillars of Catholicism—gatherings around the book and the bread; traditional prayers and songs; retreats centered on the wisdom of the saints; an understanding of life as a form of discipleship—will be unshaken.

[…]

The future will come at us invisibly, frame by frame, as it always does—comprehensible only when run together and projected retrospectively at some distant moment. But it is coming. One hundred years from now, there will be a Catholic Church. Count on it. If, down through the ages, it was appropriate for the Church to take on the political structures of the broader culture—imperial Rome, feudal Europe—then why shouldn’t Catholicism now absorb the ethos and form of liberal democracy? This may not be inevitable, but it is more than possible. The Church I foresee will be governed by laypeople, although the verb govern may apply less than serve. There will be leaders who gather communities in worship, and because the tradition is rich, striking chords deep in human history, such sacramental enablers may well be known as priests. They will include women and married people. They will be ontologically equal to everyone else. They will not owe fealty to a feudal superior. Catholic schools and universities will continue to submit faith to reason—and vice versa. Catholic hospitals will be a crucial part of the global health-care infrastructure. Catholic religious orders of men and women, some voluntarily celibate, will continue to protect and enshrine the varieties of contemplative practice and the social Gospel. Jesuits and Dominicans, Benedictines and Franciscans, the Catholic Worker Movement and other communities of liberation theology—all of these will survive in as yet unimagined forms. The Church will be fully alive at the local level, even if the faith is practiced more in living rooms than in basilicas. And the Church will still have a worldwide reach, with some kind of organizing center, perhaps even in Rome for old times’ sake. But that center will be protected from Catholic triumphalism by being openly engaged with other Christian denominations. This imagined Church of the future will have more in common with ancient tradition than the pope-idolizing Catholicism of modernity ever did. And as all of this implies, clericalism will be long dead. Instead of destroying a Catholic’s love of the Church, the vantage of internal exile can reinforce it—making the essence of the faith more apparent than ever.

What remains of the connection to Jesus once the organizational apparatus disappears? That is what I asked myself in the summer before I resigned from the priesthood all those years ago—a summer spent at a Benedictine monastery on a hill between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. I came to realize that the question answers itself. The Church, whatever else it may be, is not the organizational apparatus. It is a community of memory, keeping alive the story of Jesus Christ. The Church is an in-the-flesh connection to him—or it is nothing. The Church is the fellowship of those who follow him, of those who seek to imitate him—a fellowship, to repeat the earliest words ever used about us, of “those that loved him at the first and did not let go of their affection for him.”