❥

April 26, 2018Anguish and suffering visualized in memoriam.

“The tortuous road which has led from Montgomery, Alabama…”

Martin Luther King, Jr.

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — In a plain brown building sits an office run by the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, a place for people who have been held accountable for their crimes and duly expressed remorse.

Just a few yards up the street lies a different kind of rehabilitation center, for a country that has not been held to nearly the same standard.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opens Thursday on a six-acre site overlooking the Alabama State Capitol, is dedicated to the victims of American white supremacy. And it demands a reckoning with one of the nation’s least recognized atrocities: the lynching of thousands of black people in a decades-long campaign of racist terror.

At the center is a grim cloister, a walkway with 800 weathered steel columns, all hanging from a roof. Etched on each column is the name of an American county and the people who were lynched there, most listed by name, many simply as “unknown.” The columns meet you first at eye level, like the headstones that lynching victims were rarely given. But as you walk, the floor steadily descends; by the end, the columns are all dangling above, leaving you in the position of the callous spectators in old photographs of public lynchings. [NYTimes]

‘A Lynching Memorial in Montgomery; the country has never seen anything like it.’

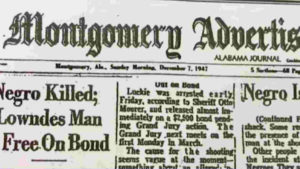

In the century after the Civil War, more than 4,000 black Americans were lynched. Men, women and children were publicly tortured and killed in acts of mob violence meant to incite fear. (1A:NPR)

‘It’s time to end the silence.’

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI)

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) is committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.

Founded in 1989 by Bryan Stevenson, a widely acclaimed public interest lawyer and best-selling author of Just Mercy, EJI is a private, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. We work with communities that have been marginalized by poverty and discouraged by unequal treatment, and we are committed to changing the narrative about race in America.

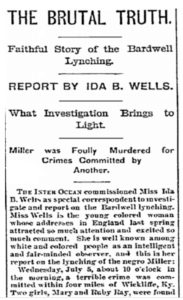

“Bryan Stevenson wants people to examine an era of American history that goes ignored — a chapter often left untold. It was a time, he says, of domestic terrorism.

Between 1877 and 1950, more than 4,400 black people died by lynching, according to statistics compiled by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization that provides legal representation to inmates and works to alleviate racial and economic injustice.

You’ve got to first tell the truth about what happened and then you can begin to understand what is required to recover, to make repairs, to restore, to reconcile. And I don’t want to deny any county in America that has a history of lynching an opportunity to localize this project, this effort.

I really do believe that the great evil of American slavery was this narrative of racial difference. This ideology of white supremacy. Our 13th Amendment ended involuntary servitude and forced labor, but it did not end this narrative of racial difference. Because of that I don’t think slavery ended, I think it just evolved and that’s what created decades of terrorism and lynching.

More than 6 million people fled the American South during this period of time, and the demographic geography of our nation was shaped by this violence.” [LATimes]

It was a time, he says, of domestic terrorism.

In context of ‘domestic terrorism’ is the unfolding story of ‘white power’ in America.

NPR

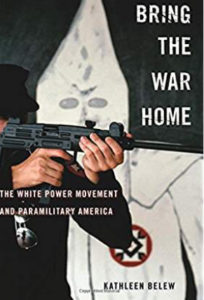

“Kathleen Belew, who has spent more than 10 years studying America’s White Power movement, traces the movement’s rise to the end of the Vietnam War, and the feeling among some “white power” veterans that the country had betrayed them.

In her new book, Bring the War Home, Belew argues that as disparate racist groups came together, the movement’s goal shifted from one of “vigilante activism” to something more wide-reaching: “It’s aimed at unseating the federal government. … It’s aimed at undermining infrastructure and currency to foment race war.

So if you think about the Klan in the 1920s, which is the example that most people are familiar with, it’s very overtly and properly nationalist. … It was out in the mainstream. It was very social. It was very overt. It was purported to be “for America” and their slogan indeed was “100 percent Americanism.”

So fast forward to 1983, and we’re looking at something completely different. This is now a coalition of united racist groups that is openly anti-government, that is focused on a transnational white nation and that is using texts and ideologies that call for an apocalyptic confrontation with everybody else.

“The White Power movement in America wants a revolution.”

Bring the War Home is a tour de force. An utterly engrossing and piercingly argued history that tracks how the seismic aftershocks of the Vietnam War gave rise to a white power movement whose toxic admixture of violent bigotry, antigovernmental hostility, and racial terrorism helped set the stage for Waco, the Oklahoma City bombing, and, yes, the presidency of Donald Trump.”―Junot Díaz

“Many people thought that they were living through a real progress moment of American history, and we had this idea, even as historians, of a “post-racial” moment, or a colorblind moment, or a multicultural moment. And I think what this story shows us is where overt racism went during the time that we thought of as peaceful and race-neutral. And that instead we were looking at this submerging and resurging story.” [Belew]

“Anyway, y’all need to come to Montgomery and see this memorial.”

John Legend