✿

January 29, 2017#WeThePeople

“But often, what we want is traction. The traction to find our footing, shift our posture, make a new decision. The traction to actually influence what happens next, not merely slip our way toward a goal of someone else’s choosing.”

-Seth Godin

Faith, History & Liberty

January 28, 2017Omid Safi

“We know that our liberty is tied to providing care for the Exiles, for refugees. When we betray the refugees, we betray our own ideals of liberty. When we turn our back on refugees, we betray America’s promise.”

~

Listen.

"You must learn one thing. The world was made to be free in." [onbeing.org]

‘…the twitch was faked.’

January 18, 2017“How long is now?

Yes, that dog is moving, but not that tree. Plants don’t move.

Well, yes, they actually do. Trees grow and then they decay. It’s just that we can’t see it happening now. It happens over a longer span. Which means it is happening now, just not in a way that matches our frame.

Getting our time scale right is essential. It affects how we perceive the growth of our organization, or the changes in our planet. It changes the way we invest in education and how we react or respond to the news media.

Do we need a sweep second hand on our wrist watch or merely a page-a-day calendar to mark the passage of time?

Alan Burdick’s new book goes into the history of how we think about now (as compared to before and after) and one particular example stuck with me: What would happen if we were creatures that lived for only 28 days? Or for 300,000 days? And if our attention span compressed or expanded along with that outcome?

Often, people who are happier or more effective than we are are merely seeing things in a different (and more appropriate) time window.

And one last example, I’ll call it Dash’s Twitch: It turns out that the insanely stressful ticker that the New York Times had on their home page on election night, the one that kept flicking back and forth, taunting everyone who saw it, was actually using “real-time” data that only updated a few times a minute.

Which means that the twitch was faked. Yes, the data was moving over time, but it wasn’t moving now.

If our now gets short enough, everything is a twitch.

And twitches, while engaging, aren’t particularly useful or productive.”

-Seth Godin

[Anil Dash is the CEO of Fog Creek Software. He also founded Makerbase, Activate, and the non-profit Expert Labs, a research initiative backed by the MacArthur Foundation and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which collaborated with the Obama White House and federal agencies.]

Gaia’s promise.

January 17, 2017‘Giving and receiving, loving and being loved, I rejoice with all creation and find in field and flower and running brook, in the sunshine and in the stillness of the night, that One Presence that fills everything. I enter into the harmony of eternal peace, into the joy of knowing that I am now in the harmony of eternal peace, into the joy of knowing that I am now in the kingdom of Gaia, which no person is excluded.’

-Science of Mind

[photo: Port Angeles, Washington, Tuesday, January 17th, 2017]

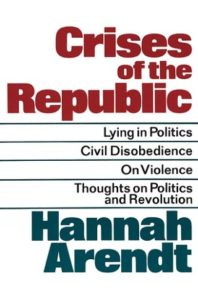

Lying in politics.

January 15, 2017‘Nowhere is this liar’s loss of perspective more damaging to public life, human possibility, and our collective progress than in politics, where complex social, cultural, economic, and psychological forces conspire to make the assault on truth traumatic on a towering scale.’

Arendt considers one particularly pernicious breed of liars — “public-relations managers in government who learned their trade from the inventiveness of Madison Avenue.”

[Note: e.g. the Pentagon budgets $5 B for PR]

In a sentiment arguably itself defeated by reality — a reality in which someone like Donald Trump sells enough of the public on enough falsehoods to get gobsmackingly close to the presidency — she writes:

The only limitation to what the public-relations man does comes when he discovers that the same people who perhaps can be “manipulated” to buy a certain kind of soap cannot be manipulated — though, of course, they can be forced by terror — to “buy” opinions and political views. Therefore the psychological premise of human manipulability has become one of the chief wares that are sold on the market of common and learned opinion.

In what is possibly the finest parenthetical paragraph ever written, and one of particularly cautionary splendor today, Arendt adds:

(Oddly enough, the only person likely to be an ideal victim of complete manipulation is the President of the United States. Because of the immensity of his job, he must surround himself with advisers … who “exercise their power chiefly by filtering the information that reaches the President and by interpreting the outside world for him.” The President, one is tempted to argue, allegedly the most powerful man of the most powerful country, is the only person in this country whose range of choices can be predetermined. This, of course, can happen only if the executive branch has cut itself off from contact with the legislative powers of Congress; it is the logical outcome in our system of government when the Senate is being deprived of, or is reluctant to exercise, its powers to participate and advise in the conduct of foreign affairs. One of the Senate’s functions, as we now know, is to shield the decision-making process against the transient moods and trends of society at large — in this case, the antics of our consumer society and the public-relations managers who cater to it.)

Arendt turns to the role of falsehood, be it deliberate or docile, in the craftsmanship of what we call history:

Unlike the natural scientist, who deals with matters that, whatever their origin, are not man-made or man-enacted, and that therefore can be observed, understood, and eventually even changed only through the most meticulous loyalty to factual, given reality, the historian, as well as the politician, deals with human affairs that owe their existence to man’s capacity for action, and that means to man’s relative freedom from things as they are. Men who act, to the extent that they feel themselves to be the masters of their own futures, will forever be tempted to make themselves masters of the past, too. Insofar as they have the appetite for action and are also in love with theories, they will hardly have the natural scientist’s patience to wait until theories and hypothetical explanations are verified or denied by facts. Instead, they will be tempted to fit their reality — which, after all, was man-made to begin with and thus could have been otherwise — into their theory, thereby mentally getting rid of its disconcerting contingency.

This squeezing of reality into theory, Arendt admonishes, is also a centerpiece of the political system, where the inherent complexity of reality is flattened into artificial oversimplification:

Much of the modern arsenal of political theory — the game theories and systems analyses, the scenarios written for imagined “audiences,” and the careful enumeration of, usually, three “options” — A, B, C — whereby A and C represent the opposite extremes and B the “logical” middle-of-the-road “solution” of the problem — has its source in this deep-seated aversion. The fallacy of such thinking begins with forcing the choices into mutually exclusive dilemmas; reality never presents us with anything so neat as premises for logical conclusions. The kind of thinking that presents both A and C as undesirable, therefore settles on B, hardly serves any other purpose than to divert the mind and blunt the judgment for the multitude of real possibilities.

But even more worrisome, Arendt cautions, is the way in which such flattening of reality blunts the judgment of government itself — nowhere more aggressively than in the overclassification of documents, which makes information available only to a handful of people in power and, paradoxically, not available to the representatives who most need that information in order to make decisions in the interest of the public who elected them. Arendt writes:

Not only are the people and their elected representatives denied access to what they must know to form an opinion and make decisions, but also the actors themselves, who receive top clearance to learn all the relevant facts, remain blissfully unaware of them. And this is so not because some invisible hand deliberately leads them astray, but because they work under circumstances, and with habits of mind, that allow them neither time nor inclination to go hunting for pertinent facts in mountains of documents, 99½ per cent of which should not be classified and most of which are irrelevant for all practical purposes.

[…]

If the mysteries of government have so befogged the minds of the actors themselves that they no longer know or remember the truth behind their concealments and their lies, the whole operation of deception, no matter how well organized its “marathon information campaigns,” in Dean Rusk’s words, and how sophisticated its Madison Avenue gimmickry, will run aground or become counterproductive, that is, confuse people without convincing them. For the trouble with lying and deceiving is that their efficiency depends entirely upon a clear notion of the truth that the liar and deceiver wishes to hide. In this sense, truth, even if it does not prevail in public, possesses an ineradicable primacy over all falsehoods.

She extrapolates the broader human vulnerability to falsehood:

The deceivers started with self-deception.

[…]

The self-deceived deceiver loses all contact with not only his audience, but also the real world, which still will catch up with him, because he can remove his mind from it but not his body.

-Maria Papova/brainpickings

The New Yorker

RICHARD RORTY’S PHILOSOPHICAL ARGUMENT FOR NATIONAL PRIDE

[Stephen Metcalf]

“In the days leading up to and following the Presidential election, a seemingly prophetic passage from the late philosopher Richard Rorty circulated virally on the Internet. The quote, which was subsequently written about in the Timesand the Guardian and on Yahoo and the Web site for Cosmopolitan magazine, is from his book “Achieving Our Country,” published in 1998. It is worth quoting at length:

Members of labor unions, and unorganized and unskilled workers, will sooner or later realize that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or to prevent jobs from being exported. Around the same time, they will realize that suburban white-collar workers—themselves desperately afraid of being downsized—are not going to let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for anyone else.

At that point, something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots. . . . Once the strongman takes office, no one can predict what will happen.

The chilling precision of these words resulted in renewed interest in Rorty, who died in 2007. Eighteen years after its release, “Achieving Our Country” sold out on Amazon, briefly cracking the site’s list of its hundred top-selling books. Harvard University Press decided to reprint it.

Rorty’s new fans may be surprised, opening their delivery, to discover a book that has almost nothing to do with the rise of a demagogic right and its cynical exploitation of the working class. It is, instead, a book about the left’s tragic loss of national pride. “National pride is to countries what self-respect is to individuals, a necessary condition for self-improvement,” Rorty writes in the book’s opening sentence, before describing in grim detail how the democratic optimism, however qualified, of Walt Whitman, John Dewey, and James Baldwin has been abandoned in favor of what he calls a “blasé” and “spectatorial” left.

Newcomers to Rorty and “Achieving Our Country” may be surprised on a second count as well. The Times piece about the new interest in the book summarized its argument like so: “In universities, cultural and identity politics replaced the politics of change and economic justice.” This is broadly accurate, but incomplete. Rorty, in “Achieving Our Country,” shows unqualified admiration for the expansion of academic syllabi to include nonwhite and non-male authors, and describes such efforts as one means of awakening students to the “humiliation which previous generations of Americans have inflicted on their fellow citizens.” He adds, without reservation, “Encouraging students to be what mocking neoconservatives call ‘politically correct’ has made our country a far better place.”

Rorty’s only issue with identity politics was that the left, having worked so hard to transfer stigmatic cruelty away from received categories like race and gender, had done too little to prevent that stigma from landing on class—and that the white working class, finding itself abandoned by both the free-market right and the identity left, would be all too eager to transfer that stigma back to minorities, immigrants, gays, and coastal élites. (Hence the viral prophecy.)

The principal object of Rorty’s derision was neither identity politics nor the rise of an ignoble free-market right but a peculiar form of decadence, which his larger intellectual project aimed to counter. I knew Rorty a little; he was a shy and gentle man, a red-diaper baby who grew up to be a bird-watcher and a savorer of Proust and Kant in their original languages. But his loathing of the academic left was neither shy nor gentle. The “Foucauldian” left, he writes in “Achieving Our Country,” “represents an unfortunate regression to the Marxist obsession with scientific rigor.” In the specific case of Foucault, this involved locating the “ubiquitous specter” known as “power” everywhere, and conceding that we are without agency in its presence. “To step into the intellectual world which some of these leftists inhabit is to move out of a world in which citizens of a democracy can join forces to resist sadism and selfishness into a Gothic world in which democratic politics has become a farce,” he writes.

How could Rorty have celebrated the rise of identity politics in the university while also deriding the major trends in critical theory as illiberal and decadent? And how did his exhortation for a renewed national pride connect with his earlier, more technical work on human mentality and the foundations of knowledge? Early in his career, Rorty had been preoccupied by the major questions of modern philosophy as they first arose in the seventeenth century, alongside the rise of experimental science. Is the human mind an object in the world, like all the other objects in the world? Is it, too, universally law-obedient to physics? And, if it is law-obedient, do we lack agency and, like other objects, inherent dignity?

Instead of solving these problems, Rorty thought we could ditch them, just as Descartes had ditched the problems of thirteenth-century scholasticism, and at a similarly low cost to the progress of human knowledge. The cheerfully non-philosophical way to ditch them was to ignore them, like most healthy people do. The slightly more philosophical method was to notice that people argued from, rather than to, their moral intuitions—an observation that may encourage us to accept that truth is at best a matter of consensus, not an observable fact of the world. The most philosophical way to abandon them was therapeutically: one could relive the philosophical past the same way an analysand relives her emotional past. By drawing, inch by agonizing inch, an unconscious pattern to the surface, one might discard it forever.

Around the same time Rorty completed his metaphysical therapy, and was reinventing himself as a general-interest writer, his peers in the English department were replacing the categories of mind and world with language and text. They were, in other words, reproducing the epistemological conundrums that had bedeviled modern philosophy since Descartes. Instead of ditching the old neurotic patterns, literary theory repeated them ad nauseum. Problems of knowledge became problems of interpretation. The glamour of its European intellectualism aside, this meant only that literary theory knocked back and forth between the assertion that nothing can be known—versions of this skepticism are found in Descartes, Hume, Berkeley, and Kant—and the assertion that skepticism can be vanquished when knowledge is reconstructed upon a new foundation.

Foucault rode this line perfectly. He said that all knowledge was inherently unstable, because it was historically contingent, and he built a new way of knowing around the master term “power.” The primal Foucauldian move is to locate abstract and universal rights, reason, and the notion of the human within concrete social practices, and show how they were coercive or hypocritical—or sadistic—from the start. The perfect symbol for liberal modernity is a prison, as governed by a panopticon, an instrument of universal surveillance. Point taken; but Rorty believed that, in addressing more or less all of humanity as his fellow-prisoners, Foucault was being decadent, and not simply because he was weakening the distinction between metaphorical and actual inmates. Foucault made seeing, or, really, seeing through, into a revolutionary activity, while implying that only an apocalyptic transformation in human thought might liberate us.

Foucault was a great philosopher. He worked tirelessly on behalf of prison reform for actual prisoners, and he was as canny as anyone about his own epistemological biases. Rorty and Foucault were, however, as temperamentally antithetical as two human beings can be. From intellectual habits that Rorty distrusted, Foucault moved on to a belief that Rorty detested. After exposing liberalism as a lie, Foucault then asserted that illiberalism was true to our nature. At times a fairly vulgar Nietzschean, he insisted that the substrate of our common reality, however we might suppress it, was cruelty. Shame is our hidden essence; the ugliest part of a thing is its truest part; being decent or kind or liberal is a sign of self-suppression or weakness; cynicism is knowledge. Here, the various tributaries of American nihilism flow into one another; a knowing passivity that regards cynicism as political courage leads to the rejection of liberal democracy on a juvenile dare. It was against just this sort of foolishness that Rorty wrote ‘Achieving Our Country.'”

Adrift

Everything is beautiful and I am so sad.

This is how the heart makes a duet of

wonder and grief. The light spraying

through the lace of the fern is as delicate

as the fibers of memory forming their web

around the knot in my throat. The breeze

makes the birds move from branch to branch

as this ache makes me look for those I’ve lost

in the next room, in the next song, in the laugh

of the next stranger. In the very center, under

it all, what we have that no one can take

away and all that we’ve lost face each other.

It is there that I’m adrift, feeling punctured

by a holiness that exists inside everything.

I am so sad and everything is beautiful.

-Mark Nepo

‘Become a lake.’

William James:

It is only by risking ourselves

from one hour to another

that we live at all.

“An aging Hindu master grew tired of his apprentice complaining and so, one morning, sent him for some salt. When the apprentice returned, the master instructed the unhappy young man to put a handful of salt in a glass of water and then to drink it. “How does it taste?” the master asked. “Bitter,” spit the apprentice. The master chuckled and then asked the young man to take the same handful of salt and put it in the lake. The two walked in silence to the nearby lake and once the apprentice swirled his handful of salt in the water, the old man said, “Now drink from the lake.” As the water dripped down the young man’s chin, the master asked, “How does it taste?” “Fresh,” remarked the apprentice. “Do you taste the salt?” asked the master. “No,” said the young man. At this the master sat beside this serious young man, who so reminded him of himself, and took his hands, offering: “The pain of life is pure salt; no more, no less. The amount of pain in life remains exactly the same. However, the amount of bitterness we taste depends on the container we put the pain in. So when you are in pain, the only thing you can do is to enlarge your sense of things. Stop being a glass. Become a lake.”

‘Greatest office in democracy? Citizen.’

January 12, 2017︶⁀°• •° ⁀︶

Democracy is the most fragile thing on earth, for what does it rest upon? You and me, and the fact that we agree to maintain it. The moment either of us says we will not, that’s the end of it. It doesn’t rest on anything but us; it doesn’t rest on armed force, the moment it does it isn’t democracy. It isn’t something to kick around or experiment with.

-Allen Drury, Stanford University

[age 19]

Context.

January 7, 2017January 5, 2017

‘You shall no longer take things at second or third hand,

nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on

the specters in books;

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take

things from me;

You shall listen to all sides, and filter them from yourself.

-Walt Whitman

Indivisible Guide

‘The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves.

-Abraham Lincoln

Former congressional staffers reveal best practices for making Congress listen.

Seth Godin

The Candy Diet

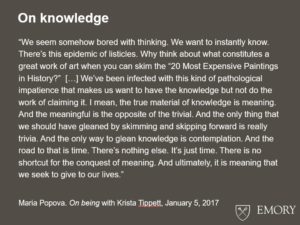

If we don’t care to learn more, we won’t spend time or resources on knowledge.

“The bestselling novel of 1961 was Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent. Millions of people read this 690-page political novel.

In 2016, the big sellers were coloring books.

Fifteen years ago, cable channels like TLC (the “L” stood for Learning), Bravo and the History Channel (the “History” stood for History) promised to add texture and information to the blighted TV landscape. Now these networks run shows about marrying people based on how well they kiss.

And of course, newspapers won Pulitzer prizes for telling us things we didn’t want to hear. We’ve responded by not buying newspapers any more.

The decline of thoughtful media has been discussed for a century. This is not new. What is new: A fundamental shift not just in the profit-seeking gatekeepers, but in the culture as a whole.

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler.”*

[*Ironically, this isn’t what Einstein actually said. It was this, “It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” Alas, I’ve been seduced into believing that the shorter one now works better.]

Is it possible we’ve made things simpler than they ought to be, and established non-curiosity as the new standard?

We are certainly guilty of being active participants in a media landscape that breaks Einstein’s simplicity law every day. And having gotten away with it so far, we’re now considering removing the law from our memory.

The economics seem to be that the only way to make a living is to reach a lot of people and the only way to reach a lot of people is to race to the bottom, seek out quick clicks, make it easy to swallow, reinforce existing beliefs, keep it short, make it sort of fun, or prurient, or urgent, and most of all, dumb it down.

And that’s the true danger of anti-intellectualism. While it’s foolish to choose to be stupid, it’s cultural suicide to decide that insights, theories and truth don’t actually matter. If we don’t care to learn more, we won’t spend time or resources on knowledge.

We can survive if we eat candy for an entire day, but if we put the greenmarkets out of business along the way, all that’s left is candy.

Give your kid a tablet, a game, and some chicken fingers for dinner. It’s easier than talking to him.

Read the short articles, the ones with pictures, it’s simpler than digging deep.

Clickbait works for a reason. Because people click on it.

The thing about clickbait, though, is that it exists to catch prey, not to inform them. It’s bait, after all.

The good news: We don’t need many people to demand more from the media before the media responds. The Beverly Hillbillies were a popular show, but that didn’t stop Star Trek from having a shot at improving the culture.

The media has always bounced between pandering to make a buck and upping the intellectual ante of what they present. Now that this balance has been ceded to an algorithm, we’re on the edge of a breakneck race to the bottom, with no brakes and no break in sight.

Vote with your clicks, with your sponsorship, with your bookstore dollars. Vote with your conversations, with your letters to the editor, by changing the channel…

Even if only a few people use precise words, employ thoughtful reasoning and ask difficult questions, it still forces those around them to catch up. It’s easy to imagine a slippery slope down, but there’s also the cultural ratchet, a positive function in which people race to learn more and understand more so they can keep up with those around them.

Turn the ratchet. We can lead our way back to curiosity, inquiry and discovery if we (just a few for now) measure the right things and refuse the easy option in favor of insisting on better.”

Fact from Fiction

Higher Ed takes on Fake News Epidemic

Universities are working to tackle a digital age issue that’s making it more difficult to discern fact from fiction

Political transparency advocacy group VoteSmart has cataloged and published speeches, voting records, campaign financing and news coverage of more than 40,000 candidates for political office throughout the United States since 1992, and next month, will relocate to Drake University as its new national headquarters.

Officials say the relocation continues a tradition of partnership between VoteSmart and higher education, as the office has found permanent stations at schools like Oregon State University, the University of Arizona, the University of Southern California and the University of Texas at Austin. Throughout its history, they say, the organization has looked to higher ed as the lightning rod for change in political structure, social awareness, and today what some call a new threat to democracy: fake news.

The rise of fake news has become a wide topic of corporate and consumer culture over the last six months, peaking with the 2016 election and intense scrutiny of traditional and social media outlets and the impact of false stories which helped to drive false narratives about political candidates and events.

Facebook, the world’s largest social media platform, this week announced steps to limit the sharing and publishing of fake news on its site, which estimates suggest reaches 170 million North Americans daily. VoteSmart officials say colleges and universities are central to challenging news organizations and social platforms to stem the effects of fake news, which is part of the historic role of social change and information awareness that has spurred student movements for generations.

At the University of Maryland, journalism faculty remains in regular conversation about teaching quality industry practices, while giving students the full scope of their responsibility to provide accuracy and timeliness.

“We’re teaching students that they are going to have a tougher time with readers just assuming that they are credible,” says Lucy A. Dalglish, dean of UMD’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism. “Now more than ever before. you have less leeway to make mistakes.”

She says that the university has developed media literacy training for faculty and students with a specific portion of the course dedicated to discerning good and bad news sources. While Internet technology has made the job tougher for debunking bad news sources, she says the journalists can still do more to help the public understand why information is important, and how it is cultivated for reporting.

“We also need to teach them to stick up for themselves and for the industry they are going into. It’s also important to do a better job of explaining where we got information. Mention open records, public meeting acts so people know that the reporting is based upon something.”

The journalism school is also developing a pilot program for incoming students to learn better Internet search skills, and currently offers a mandatory skills source for freshmen and sophomores in conjunction with the school’s library to receive research insight from credentialed librarians.

“Younger people almost always take the more idealistic side of life, and have an enthusiasm for truth and accuracy,” says VoteSmart founding board member and senior consultant Adelaide Kimball. “They aren’t afraid to call out a lack of facts, and campuses have always been the appropriate places to do that.”

Kimball says that thousands of college students have helped to drive the VoteSmart agenda for decades, with its commitment to fact gathering and provision driving crossover appeal among students from a variety of college majors and career ambitions to volunteer as fact checkers and researchers. She says that any effort colleges and their students can make to reverse the effects of accepted misinformation preserves the integrity of journalism industry, and democracy at large.

“It’s becoming hard to convince people that they need the facts, that they need the truth,” says Kimball. “Somehow, we’ve got to get people to care, and to recognize what may not be accurate or fake and that they don’t accept it anyway.”

But what happens when caring turns to controversy on campus? From the 2015 Black on Campus Movement to this year’s student clashes on topics like academic freedom, free speech and white nationalism, some institutions are at odds on how to navigate areas of protest, information spreading and promotion, and social connotations carried by all areas of student mobilization.

Jennifer Glover Konfrst is an assistant professor and co-leader of Drake’s Strategic Political Communication program, and says that even in the classroom, curriculum and attitudes have shifted to analyze the effects of fake news on a public growing in its comfort with misinformation.

“In the past, we might have talked about the risks of being incorrect or sloppy in reporting, but you didn’t see it happening very often,” Konfrst says. “Now, we have the opportunity to show them this is what’s so harmful about fake news; it’s been shared 90,000 times and it’s not true, and it takes 13 hours for a story to be debunked on average online, and it’s all over the world.”

Faculty have been at the center of a specific news movement of their own in recent weeks, with the national college conservative advocacy organization Turning Point USA publishing a ‘Professor Watchlist,’designed to highlight professors whom it says are advancing liberal political agendas through teaching and in academic spaces. “TPUSA will continue to fight for free speech and the right for professors to say whatever they wish ; however students, parents, and alumni deserve to know the specific incidents and names of professors that advance a radical agenda in lecture halls,” according to a statement from its website.

The American Association of University Professors responded recently with a petition encouraging faculty members to submit their names to Turning Point USA for inclusion on the lists, suggesting that the tactics would not breed fear among the academic enterprise.

“The American Association of University Professors has supported academic freedom and opposed those who seek to curtail it for more than a hundred years, and will continue to do so, because the common good depends upon the free search for truth and its free exposition,” read a statement from the petition. “The type of monitoring of professors in which you are engaged can only inhibit the process through which higher learning occurs and knowledge is advanced.”

Konfrst, who was aware of the watchlist, says that she discloses her political affiliation at the beginning of her courses, and at their conclusion asks in her student evaluations of they felt all voices were afforded a chance to be heard.

“It’s hard, because you don’t want to have to feel like you have to prove your legitimacy to your students. I tell them that I’m going to allow all voices to be heard, I’m not going to tell you my political beliefs because it’s not about that. I put it out there that I have opinions, but I don’t think you’re going to notice them. Putting it out there is helpful, because there’s a difference in being unopinionated and being fair in your writing.”

Kimball says that collegiate response to fake news creation, ultimately, will prove to be a historic task for the sustainability of the public trust.

“We do see the advent of fake news as an enormous problem for democracy and our civic culture, she says. “I’m happy to hear that colleges are taking up this challenge immediately, because this is one of the most dangerous developments in our civic culture and probably hundreds of years, if not ever.”

“We seem to have gotten to a place, partly because of technology and people’s nature, that people have a hard time distinguishing what’s accurate and what’s not. If schools across the country can pound that into students and cover those important issues in a way that helps people to easily see what is accurate and what is not, it is a huge public service.”

✿

January 4, 2017“In dwelling, be close to the land.

In meditation, go deep in the heart.