I sat across the street from my childhood home on the cold curb in the dark and watched the party as if it were a TV on mute. Adults moved in and out of the frame of the big picture window, glasses in hand, laughing, touching one another jovially. The warmth was palpable, even though I was shivering a little bit. It was my parents’ 40th birthday party — a joint blowout to mark the arrival of middle age. Friends brought gag gifts about how “over the hill” they now were and made jokes about their waning eyesight and hearing. I remember, my 10-year-old self thinking they must be getting really old.

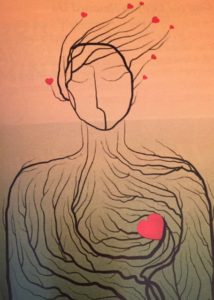

I just turned 38. It has been nearly three decades since I sat on that cold curb and watched the merriment inside, trying to wrap my brain around what it all meant. I don’t feel old at all. Some days, in fact, I feel like I’m younger than I’ve ever been — a kind of Benjamin Button, temperamentally speaking. I’ve always been too serious. Aging has helped me lighten up in all kinds of ways. I’m humbled by how hard life can be, how complex. Where I used to jump to judgment, I am now more likely to feel solidarity or sadness. That at the tragic part of the human condition or even wonder. How broken are we, and yet, how beautiful? It boggles the heart.

I want to be one of those people that widens, not narrows, as I age. And yet, as I inch closer and closer to that picture window of my parents, it is the finite nature of life that hits me hardest. Sometimes I will be sitting on the rug in the living room, listening to my youngest daughter pound dominoes (her latest obsession) into our coffee table while my oldest wraps her baby doll in a suffocating number of layers of blankets, my husband banging around in the kitchen making pasta, and time will suddenly halt into a sort of freeze frame profundity. I’ll lose my breath for a second as I think, “Wow, this is it.”

It’s not a sad “this is it.” It’s a happy “this is it.” And yet, it’s interlaced with bafflement — “so really, this is it? These are my daughters? This is my person? This is our house? Huh, amazing.”

The same sort of bafflement creeps into my workday, too. I’ll be hammering away at this keyboard, trying to put a sentence together, and I’ll realize — “Wow, this is it. This is what I do. This is what I am going to contribute to the world in this lifetime.”

I’m not a small town mayor or a nonprofit director or a judge. I’m not a single woman with no children who travels the world investigating war crimes. I’m not a portrait photographer or a chaplain. I’m not a woman who plays the blues harmonica at open mic jazz nights in little clubs in New York City.

Those were all, believe it or not, versions of myself that at one point existed in the future. And then days and decisions accumulated and I kept moving further and further into that future and these women started fading, one by one, from the potential story of my life.

And I would be lying if I said that I didn’t feel grief over their disappearance. Even Robert Frost admitted to sadness over his road not traveled, though he was sure he did it right. We are practiced and very convincing at creating the fateful narrative in reverse — everything always happens how it is supposed to. Unless it really doesn’t, in which case we pretend it did anyway. That’s what we do as humans — if we are resilient and adaptive, which most of us are, we tell ourselves the stories we need to hear in order to take the edge off of our mourning at the lives we’ll never lead.

Although… what if we might, in fact, lead them, just not this time around?

My friend Sandy, who is on the other side of 40, recently taught me another adaptation that I am reveling in. She said that after a period of feeling acute sadness over all the versions of herself she would never be — “I’ll never be a Russian painter!” she exclaimed — she decided to throw down for reincarnation. When she has a pang of sadness over a version of herself that likely won’t exist, instead of trying to banish it from her brain as quickly as possible, she delights in it, adding it to her file of “next lifetimes.” While feeling genuinely grateful for all that she is packing into this impossibly little life, she’s also conjuring and collecting these potential future versions of herself. Sandy won’t be a Russian painter tomorrow, but what if she is in another century or two? How is she to know that this is or isn’t possible? How exciting!

I don’t believe in reincarnation, per se, but that’s beside the point. I believe in the magic of what I don’t know, and I don’t know that reincarnation isn’t possible. So I’m starting to build up my portfolio of next lifetimes. I know there is beauty in limitation. And this life, with the husband banging around in the kitchen and my babies stumbling around the living room, this life with the sentences upon sentences — well, it’s a tremendous gift. I feel even more capable of recognizing that when I allow for the possibility that during some other journey, I’ll be an NBA basketball star or a labor organizer or a painter with a giant studio somewhere overlooking the water.

[Courtney E. Martin is a columnist for On Being.]